The official account of 9/11 is that it was a terrorist attack with no U.S. foreknowledge. This version of events has been challenged by a wide range of evidence, much of which is covered at these hearings. Perhaps most important is eyewitness, chemical, and visual evidence indicating the Twin Towers and Building 7 at the World Trade Center were brought down by controlled demolition. The visual evidence is something everyone can see by watching videos of the Twin Towers explode into dust from the top down, and Building 7 collapse symmetrically and initially at free-fall acceleration into its own footprint. The appearance of controlled demolition not only casts doubt on the official account of how the buildings fell, it raises obvious questions about possible official foreknowledge and complicity. These doubts and questions are compounded by the government’s failure to investigate the debris at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon for signs of explosives and incendiaries. This failure amounts to nonfeasance indicative of guilty knowledge. Official complicity is further suggested by the actions of U.S. governing authorities in the aftermath of 9/11: immediately invading Afghanistan, adopting an official policy of preemptive war, and manipulating intelligence to justify the invasion and occupation of Iraq. These actions are prima facie evidence of a preexisting agenda to contrive a pretext for waging wars of aggression in the Middle East to gain control of diminishing energy supplies. The case for suspecting 9/11 was an inside job driven by imperial ambitions is compelling and certainly sufficient to warrant national and international legal investigations.

Nevertheless, the official account of 9/11 continues to be defended by U.S. elites and accepted uncritically by large segments of the America public. No doubt, this lack of suspicion is reinforced by self-interest, nationalism, and resistance to cognitive dissonance, but it is also based to a considerable extent on what seems to be common sense. People doubt that U.S. public officials would have allowed, much less have planned and organized an attack that killed thousands of U.S. citizens and threatened the nation’s centers of finance and government. Many Americans believe that the vast majority of public servants would refuse to go along with such a treasonous plot and that, in any event, elements of the government could not organize and execute such a complex operation without being detected or without someone talking.

This paper aims to dispel this seemingly straightforward perspective by analyzing 9/11 scientifically as a State Crime Against Democracy (SCAD). The analysis is scientific in the sense that it employs theory-based empirical observation to uncover patterns of variation in a general phenomenon. Science has historically overcome popular prejudices by re-conceptualizing everyday experience and pointing out unnoticed facts that are more or less in plain sight. Before scientific discoveries in astronomy and physics in the 16th and 17th centuries, people believed the earth was the center of the universe and the sun, the planets, and the stars revolved around it. Common sense said the earth could not be spinning and flying through space, just as common sense today says 9/11 could not have been an inside job. Galileo opened people’s eyes with the concept of gravity along with some surprising but irrefutable observations. This paper will do this, in a small way, with the SCAD concept and some novel observations about elite political criminality in the United States.

In a 2006 peer-reviewed journal article, I introduced the concept of State Crime Against Democracy to displace the term “conspiracy theory.” The word displace is used rather than replace because SCAD is not another name for conspiracy theory; it is a name for the type of wrongdoing about which the conspiracy theory label discourages us from speaking. Later, this paper will discuss how the label, as it is used today, was formulated and popularized in the 1960s by the CIA. For now, it is enough to acknowledge that the term conspiracy theory is applied pejoratively to allegations of official wrongdoing, which have not been substantiated by public officials themselves.

In contrast, SCADs are not allegations; they are a type of crime. SCADs are defined as concerted actions or inactions by government insiders intended to manipulate democratic processes and undermine popular sovereignty (deHaven-Smith, 2006). By definition, SCADs differ from bribery, kickbacks, bid-rigging, and other, more mundane forms of political criminality in their potential to subvert political institutions and entire governments or branches of government. They are high crimes that attack democracy itself. When, as with 9/11, they involve making war against the United States, they are also acts of treason under the U.S. Constitution.

SCADs can be and are committed at all levels of government, but this paper centers on SCADs in high office because of their grave consequences. Examples of such SCADs that have been officially proven include the Watergate break-ins and cover up (Bernstein & Woodward, 1974; Gray, 2008; Kutler, 1990; Summers, 2000); the illegal arms sales and covert operations in Iran-Contra (Kornbluh & Byrne, 1993; Martin, 2001; Parry, 1999); and the effort to discredit Joseph Wilson by revealing his wife’s status as an intelligence agent (Isikoff & Corn, 2007; Rich, 2006, 2007; Wilson, 2004).

Many other political crimes in which involvement by high officials is suspected have gone uninvestigated or have been investigated only superficially. Among these are the events referred to as 9/11. Additional examples include the fabricated attacks on U.S. ships in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964 (Ellsberg, 2002, pp. 7-20); the “October Surprises” in the presidential elections of 1968 (Summers, 2000, pp. 298-308) and 1980 (Parry, 1993; Sick, 1991); the assassinations of John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy (Fetzer, 2000; Garrison, 1988; Groden, 1993; Lane, 1966; Pease, 2003; Scott, 1993; White, 1998); the election breakdowns in 2000 and 2004 (deHaven-Smith, 2005; Miller, 2005); the October 2001 anthrax letter attacks; and the misrepresentation of intelligence to justify the invasion and occupation of Iraq (Isikoff & Corn, 2007; Rich, 2006).

This paper is divided into four parts. First, it will discuss how science and scientific concepts have been able, historically, to overturn mistaken beliefs that were widely accepted and strongly held. Second, it will explicate some dubious assumptions about elite political criminality that are embedded in our everyday perceptions of political crimes. It will also show that these assumptions create a blind spot which the SCAD concept can expose and overcome. Third, it will describe several patterns in SCADs and suspected SCADs and briefly point out what they suggest about the nature and institutional locus of state criminality in American politics. Finally, it will conclude by pointing out a few aspects of 9/11 that SCAD research suggests warrant more attention than they have thus far received.

Scientific Conceptualization

Although science is based on observation, scientific observation is more than merely looking and seeing. Modern science says the earth is spinning on its axis and revolving around the sun, and yet, clearly, the earth does not feel to us like it is moving. If the earth is spinning, why do we not fly off? What holds us to the ground? “Gravity,” you say. But can you show me this gravity? What does it look like? Where can I find it? “It is invisible,” you reply. But surely you jest. You ask me to believe in a mysterious force that I cannot see it, and the only reason you have for claiming the force exists is that (you say) the earth is spinning, when it obviously is not.

The concept of gravity is essential to the sun-centered model of the planetary system. It explains what holds people to the spinning earth as well as what holds the planets in their orbits around the sun. However, gravity is not something we can observe directly; it is a postulated force.

Galileo convinced people that gravity exists by showing them something remarkable they could see with their own eyes but had never noticed. The concept of gravity implied that, when dropped, physical objects would fall at the same rate of acceleration regardless of their size or weight because they are all pulled down by the same uniform force — the uniform force of the earth’s “gravity,” not the varying force of the objects’ “weight.” Galileo is said to have proved this by dropping objects from the leaning Tower of Pisa. The fact that objects of different weights fell at the same speed was an astounding discovery; people had seen objects fall countless times, but they had always assumed heavier objects fell faster than lighter objects. Thus, the concept of gravity pointed to an observable phenomenon that people’s conventional beliefs had prevented them from seeing.

This is also how the theory of evolution overturned the accepted idea that all the plants and animals on earth had been created in the form and diversity they display today. Contradicting the Biblical account of creation, Darwin said plants and animals evolved from simple life forms to more complex, differentiated forms (or “species”) through a process of “natural selection.” However, most people initially considered it ludicrous, not to say insulting, to suggest that humankind had descended from apes. Moreover, speciation itself cannot be observed; it is something that has already happened. We came to accept evolutionary theory not because we actually saw evolution, but because the theory led to a number of novel discoveries that had been more or less in plain sight all along. One was the fact that the characteristics of animals vary with their environments. Rabbits in snowy regions are white while in sandy regions they are tan. Another discovery was the fossil record of dinosaurs and of intermediary species between apes and human beings.

The theory of evolution also allowed us to see things about ourselves that we had never considered. Darwin himself would point out to audiences that the origin of human beings from animals is evident in our bodies. Apes and dogs have a crease in their ears where their ears bend and they can raise and lower the tips. If you feel the back of your own ear, you will find an atavistic remnant of this same crease. It is a small indentation along the back of your ear about a third of the way down.

These examples show that it is often the surprising discovery or novel observation that causes people to accept scientific theories and abandon their taken-for-granted, commonsense beliefs about how the world works. Uncovered by concept-driven and theory-driven observation, these discoveries take two forms. Some are macro-discoveries in the sense that they zoom out and point to missing pieces that fill in a larger theoretical picture. Examples of macro-discoveries include, in biology, the intermediary species between apes and human beings, or in astronomy, Keplar’s discovery that the planets move in elliptical orbits. Other discoveries are micro-discoveries in the sense that they zoom in, bringing obscure phenomena into focus. Examples of micro-discoveries include the crease in the human ear and the uniform acceleration of falling objects. In both cases, macro- and micro-, the world is seen in a new way because new concepts highlight overlooked facts and cause old perceptions to be re-interpreted. Where previously we had seen the earth as stationary and the sun as rising and setting, we now realize the sun is stationary and the earth is spinning.

Incident-Specific Myopia in Everyday Perceptions of Political Crime

The SCAD concept and SCAD research operate similarly in re-conceptualizing accepted perceptions of American politics and government. The everyday, common sense understanding of assassinations, defense failures, election breakdowns, and other unexpected political events is that they are isolated occurrences, each with its own special and distinct circumstances. This way of thinking, this tendency to see such events as unique and isolated, is common regardless of one’s views about conspiracy theories. Allegations as well as denials of elite political criminality tend to be focused on only one event at a time. There are separate combinations of official accounts and conspiracy theories for the assassination of President Kennedy, the attempted assassination of President Reagan, the October Surprise of 1980, the disputed 2000 presidential election, and so on. The Toronto Hearings were a part of this pattern, but focused on 9/11.

Even when obvious factors connect events, each incident is examined individually and in isolation. For example, John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy were brothers, both were shot in the head (unlike other victims of assassination), both were rivals of Richard Nixon, and both were killed while campaigning. Nevertheless, their assassinations are generally thought of as separate and unrelated. It is seldom considered that the Kennedy assassinations might have been serial murders. In fact, we rarely use the plural, Kennedy assassinations. In the lexicon, there is the Kennedy assassination, which refers to the murder of President Kennedy, and there is the assassination of Robert Kennedy.

This same “incident-specific myopia” is evident in perceptions of the disputed 2000 and 2004 presidential elections. Although both elections were plagued by very similar problems, and although in both cases the problems benefitted George W. Bush, the election breakdowns are not suspected of being repeat offenses by the same criminal network employing the same tactics and resources. This is not failing to connect the dots; this is seeing one dot and then another dot and never placing the dots on the same page.

Contemporary perceptions of 9/11 are no different. 9/11 and the anthrax letter attacks are viewed as separate and unrelated even though they occurred closely together in time and both were acts of terrorism.

It should be noted that this way of thinking about elite political crimes — this tendency to view parallel crimes separately and to see them as unrelated — is exactly opposite the way crimes committed by regular people are treated. If a man marries a wealthy woman and she is killed in a freak accident, and if this same man then marries another wealthy woman who also dies in an accident, foul play is naturally suspected, and the husband is the leading suspect. It is routine police protocol to look for patterns in burglaries, bank robberies, car thefts, and other crimes, and to use any patterns that are discovered as clues to the identity of perpetrators. This is Criminology 101. It is shown repeatedly in crime shows on TV. There is no excuse for our failure to apply this method to assassinations, election fiascos, and other crimes and suspicious events that shape national political priorities.

Normative Suppression of Suspicion

Americans fail to notice connections between crimes involving political elites in part because powerful norms discourage them from looking. The U.S. political class condemns, ridicules, and ostracizes anyone who speculates publicly about political criminality in its ranks. A clear example of these norms in action is the term “conspiracy theory” and its use as a pejorative to stigmatize suspicions of official complicity in troubling events. In today’s public discourse, no epithet is more effective at silencing allegations of official wrongdoing. To call an idea a conspiracy theory is to imply that anyone who endorses it is paranoid and possibly psychologically troubled.

Although the conspiracy-theory label and its pejorative connotations are taken for granted by most Americans, they actually make no sense. First, as a label for irrational political suspicions, the concept is obviously defective because political conspiracies in high office do, in fact, happen. Given that some conspiracy theories are true, it is absurd to dismiss all unsubstantiated conspiracy theories as false by definition.

Second, ridiculing suspicions about political elites is blatantly inconsistent with American political traditions. In fact, the Declaration of Independence itself espouses a conspiracy theory. It claims that “a history of repeated injuries and usurpations” by King George proved the king was plotting to establish “an absolute tyranny over these states.” The bulk of the document is devoted to detailing the abuses evincing the king’s tyrannical designs.

Third, in disparaging speculation about possible elite criminality, the conspiracy-theory label harbors a theory of its own. In the post-WWII era, official investigations have attributed assassinations, election fiascos, defense failures, and other suspicious events to such unpredictable, idiosyncratic forces as lone gunmen, antiquated voting equipment, bureaucratic bumbling, and innocent mistakes, all of which suspend numerous and accumulating qui bono questions. In effect, political elites have answered conspiracy theories with coincidence theories.

If there is any logical reason for skepticism about conspiracy theories, it is the idea that conspiracy theories could not be true because secrets in the United States cannot be kept – someone would talk. This strikes many Americans as common sense. However, it is simply untrue, and Americans, of all people, should know it. The Manhattan Project took several years and involved tens of thousands of people, but it did not become known to outsiders, either in the public or inside the government, until the first atomic bombs were dropped. Even President Truman did not learn of the project until he had been president for a week (McCullough, 1992, pp. 376-379). Similarly, secrecy was maintained throughout World War II about America’s success in breaking German and Japanese encryption systems. Clearly, when the U.S. government wants to keep secrets, it can do so even when the secrets must be harbored by many people and multiple agencies.

If the conspiracy-theory label is nonsensical, un-American, based implicitly on a “coincidence theory,” and contradicted by obvious examples of well kept secrets, why did people start using it in the first place? The truth is the conspiracy-theory label and its pejorative connotations did not originate and spread spontaneously in the natural communicative processes of civil society. Documentary evidence shows the term was actively deployed by the CIA as a dismissive catchall for criticisms of the Warren Commission’s conclusion that President Kennedy was assassinated by a lone gunman. The CIA issued instructions for its agents to urge “propaganda assets” and “friendly elite contacts (especially politicians and editors)” to rebut the Warren Commission’s critics with a series of talking points. The CIA mobilized a coordinated media campaign labeling the Warren Commission’s critics as “conspiracy theorists,” questioning their motives, and alleging that “parts of the conspiracy talk appear to be deliberately generated by Communist propagandists.”

Today, this tactic of covertly manipulating public discourse is being referred to as “cognitive infiltration.” Cass Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule coined this term in a 2009 journal article on the “causes and cures” of conspiracy theories. Sunstein is a Harvard law professor appointed by President Obama to head the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Especially alarmed about conspiracy theories of 9/11, Sunstein and Vermeule advocate a government program of “cognitive infiltration” to covertly “disrupt” online discussions by conspiracy-theory groups and networks (Sunstein and Vermeule 2009, 218-219, 224-226). The cynicism and hypocrisy of this proposal are breathtaking. Sunstein and Vermeule call for the government to conspire against citizens who discuss with one another suspicions of government conspiracies, which is to say they are urging the U.S. government to do precisely what they want citizens to stop saying the government does.

Given the insight-disabling effects of the conspiracy-theory meme, we should be wary of the term “cognitive infiltration,” especially since it was put forward in a plan for manipulating public discourse. In the CIA’s operation to stigmatize conspiracy theorizing, the agency injected a destructive meme into the communicative organs of civil society for the purpose of influencing public-opinion formation. When cognitive infiltration involves planting memes, it would be more accurately described as “linguistic thought control” or “subliminal indoctrination.”

The SCAD Concept

The victim’s “standpoint.” The SCAD concept is intended to function like a corrective lens to shift the standpoint and widen the angle of political crime observation. In effect, everyday (case-by-case) perceptions of assassinations, defense failures, election fiascos, and similar events view these events from the perspective of a victim, a perspective that magnifies the threat and/or the vulnerability of the target. This is understandable; in the aftermath of shocking events, threats loom large in our thoughts because we may be frightened and are struggling to make sense of the incident and its implications.

The victim perspective is frequently evident in the photographic images that become iconographic: President and Mrs. Kennedy in their limo with the Texas School Book Depository rising above them in the background; a close-up, full-body picture taken from below eye level of Lee Harvey Oswald holding a rifle; Robert Kennedy prostrate on the floor, dying, surrounded by standing onlookers.

To this day, when we are reminded of 9/11, the images that come to mind “see” the destruction “from below.” If they are images of the Twin Towers, their perspective is from street level looking up. For days or weeks after the events, the Twin Towers appeared in our mind’s eye whenever we saw commercial airplanes flying overhead. Even now, it takes a willful act of imagination to visualize the hijacked planes from a different perspective. You can experience this for yourself: Try to visualize the scene from a standpoint above the buildings and the approaching plane. For many people, the image is vague, blurry, and unstable.

Of course, in the case of 9/11, the natural tendency to magnify the threat and see it “from below” was enhanced by the fact that the threat came from the sky, but it was also abetted by a decision of the U.S. government to sequester photos that looked down on the carnage. Before, during, and after the Twin Towers imploded, thousands of photos were taken of the World Trade Center from a police helicopter flying overhead. These are the only images in existence that show the destruction from above, and yet the photos were withheld from the public for over 8 years. They came out only because ABC News filed a request under the Freedom of Information Act with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the agency responsible for investigating the WTC destruction.

Significantly, no official explanation for sequestering these photos has been offered despite a New York Times editorial criticizing the action after the photographs were released in February 2010. The editorial focused on how these photos would have changed popular perceptions of 9/11 had they been released sooner. The editorial was titled “9/11 From Above.” It is a troubled and troubling missive that flirts with dark suspicions but ultimately leaves them unspoken. The editorial says it is “surprising to see these photographs now in part because we should have seen them sooner.” Pointing out that “9/11 has resolved itself into a collection of core images,” the authors imply that these images have left Americans with a picture of events that is blurry and too close up. Implicitly contrasting this collection of images with the new photos, the editorial says, because the photos from the helicopter were “shot from on high, they capture with startling clarity both the voluminousness of the pale cloud that swallowed Lower Manhattan and the sharpness of its edges.” The authors do not explain what this reveals about 9/11, but they clearly believe it is significant, for they conclude by saying the photos “remind us of how important it is to keep enlarging our sense of what happened on 9/11, to keep opening it to history.”

The SCAD standpoint. The SCAD construct shifts our perspective conceptually. It raises the standpoint of observation and inquiry above isolated incidents by directing attention to the general phenomenon of elite political criminality. Similar to research on white collar crime, domestic violence, serial murder, and other crime categories, SCAD research seeks to identify patterns and commonalities in SCAD victims, tactics, timing, those who benefit, and other SCAD characteristics. These patterns and common traits are macro-discoveries that offer clues about the motives, institutional location, skills, and resources of SCAD perpetrators. They also provide a basis for understanding and mitigating the criminogenic circumstances in which SCADs arise. In turn, as patterns and commonalities across multiple state political crimes are identified, they point to micro-discoveries by suggesting characteristics to look for when investigating individual incidents.

A variety of SCADs and suspected SCADs have occurred in the United States since World War II. Table 1 contains a list of 19 known SCADs and other counter-democratic crimes, tragedies, and suspicious incidents for which evidence of U.S. government involvement has been uncovered. The table identifies tactics, suspects, policy consequences or aims, and includes a summary assessment of the degree to which official complicity has been confirmed. For research purposes, the universe of SCADs must include not only those that have been officially investigated and confirmed, but also suspected SCADs corroborated by evidence that is credible but unofficial. Although including the latter brings some risk of error, excluding them would mean accepting the judgment of individuals and institutions whose rectitude and culpability are at issue.

Before discussing some telling patterns in Table 1, a general observation is appropriate: American democracy in the post-WWII era has been riddled with elite political crimes. This is evident from a simple review of elections. Presidential elections were impacted by assassinations, election tampering, and/or intrigues with foreign powers in 1964, 1968, 1972, 1980, 2000, and 2004. This amounts to over a third of all presidential elections since 1948 and fully half of all elections since 1964. Moreover, two-thirds of these tainted elections were marred by multiple crimes:

- 1964 included the assassinations of JFK and Oswald, plus the Gulf of Tonkin incident;

- 1968 included the assassination of RFK plus the 1968 October Surprise;

- 1972 included the stalking of Ellsberg, the crimes of Watergate, and the attempted assassination of Wallace; and

- 2004 included bogus terror alerts plus election tampering.

Table 4-1: Crimes against American Democracy Committed or Allegedly Committed by Elements of the U.S. Government

| Crime or Suspicious Event, Time Frame, and Modus Operandi | Perpetrator Motive or Policy Implication | Suspected or Confirmed Perpetrator | Degree of Confirmation of Gov’t Role |

| McCarthyism (fabricating evidence of Soviet infiltration). 1950-1955. MANIPULATION OF DEFENSE INFO/POLICY | Large scale purge of leftists from government and business. POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM | Joseph McCarthy, with others. Although his tactics were not investigated, they were discredited in Senate hearings, and a Democratic Senate censured the Republican Senator. | High (Fried, 1990; Johnson, 2005) |

| Assassination of President Kennedy. 1963. ASSASSINATION | Lyndon Johnson’s Presidency; Escalation of the Vietnam War. CONTROL WAR POLICY | Probably right-wing elements in CIA, FBI, and Secret Service. Possible involvement of Johnson and/or Nixon. | Medium (Fetzer, 2000; Groden, 1993; Garrison, 1988; Lane, 1966; Scott, 1993; White, 1998) |

| Assassination of Lee Harvey Oswald. 1963. ASSASSINATION | Oswald’s ties to the CIA remain hidden. A trial of Oswald is avoided. CONCEAL CRIME | Jack Ruby, who had ties to the CIA and organized crime. Part of overall JFK assassination plot. | Medium (Scott, 1993) |

| Fabricated Gulf of Tonkin incident. 1964. PLANNED INTERNATIONAL EVENT | Large expansion of military resources committed to the Vietnam conflict. CONTROL WAR POLICY | President Johnson and Secretary of Defense McNamara falsely claimed that North Vietnam attacked a U.S. military ship in neutral waters. | High (Ellsberg, 2002, pp. 7-20). |

| Assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy. 1968. ASSASSINATION | Weak Democratic nominee (Humphrey); election of Nixon; no further investigation of JFK assassination; continued escalation of Vietnam conflict. CONTROL WAR POLICY | Rightwing elements in the CIA and FBI, with likely involvement of Nixon. Suspicions of government involvement are based largely on number of bullets shot and failure to fully investigate. | Low (Pease, 2003b) |

| October Surprise of 1968. 1968. MANIPULATION OF DEFENSE INFO/POLICY | Secure election of Richard Nixon as President by convincing South Vietnam to withdraw from Johnson’s peace negations for ending the Vietnam War POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM | Nixon and intermediaries with South Vietnam leadership. | High (Summers, 2000, pp. 298-308; also supported by tapes of Johnson and Nixon) |

| Burglary of the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office. 1971. BURGLARY | Discredit Ellsberg. Exposure of the break-in prevented use of the stolen information. CONTROL WAR POLICY | President Nixon, White House staff, and CIA operatives or former operatives. The crime was discovered during Ellsberg’s trial, not in an investigation of the break-in. | High (Ellsberg, 2002) |

| Attempted assassination of George Wallace. 1972. ASSASSINATION | Wallace taken out of 1972 election and Nixon reelected. Wallace was likely to win 7 southern states, forcing the election to be decided by a Democratically controlled Congress. POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM | Arthur Bremer. Some circumstantial evidence points to the involvement of Nixon via the Watergate plumbers. Evidence includes comments of Nixon. | Medium (Bernstein & Woodward, 1974, 324-330; Carter, 2000) |

| Watergate Break In. 1972. BURGLARY/WIRETAPPING | Weak Democratic nominee (McGovern) and reelection of Nixon. POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM | President Nixon, White House staff, and CIA operatives or former operatives. | High (Bernstein & Woodward, 1974) |

| Attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan. 1981. ASSASSINATION | V.P. Bush’s role in the Administration is strengthened, especially in relation to covert operations in the Mid-East and Latin America. CONTROL WAR POLICY | John Hinkley. Evidence shows connections between Hinkley’s family and the family of V.P. Bush. | Low (Bowen, 1991; Wiese & Downing, 1981) |

| October Surprise of 1980. 1980. MANIPULATION OF DEFENSE INFO/POLICY | Secure election of Ronald Reagan as President by making deal with Iranians to sell them U.S. arms if hostages not released until after election POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM | Reportedly arranged in a meeting in Paris attended by George H.W. Bush, William Casey, and Robert Gates. Confirmed later by Iranian officials. Iran-Contra arms dealing appears to have been an extension of this earlier effort. | High (Parry, 1993; Sick, 1991) |

| Iran-Contra. 1984-1986. MANIPULATION OF DEFENSE INFO/POLICY | Release of hostages; civil war in Nicaragua. CONTROL WAR POLICY | President Reagan, Vice President Bush, CIA, military. | High (Kornbluh & Byrne, 1993; Martin, 2001; Parry, 1999) |

| Florida’s disputed 2000 presidential election. 2000. ELECTION TAMPERING | Legally mandated recount is blocked; G.W. Bush becomes president through U.S. Supreme Court decision. POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM | Jeb Bush and Katherine Harris developed flawed felon disenfranchisement program. Jeb Bush, Harris, and Tom Feeney colluded to block recount. Harris facilitated counting of fraudulent overseas military ballots. | High (Barstow & Van Natta, 2001; deHaven-Smith, 2005) |

| Events of 9/11. 2001. PLANNED INTERNATIONAL EVENT | Bush popularity rises; defense spending increases; Republicans gain in off-year elections; military invasion of Afghanistan; pretext for invasion of Iraq. CONTROL WAR POLICY | Evidence of controlled demolition of buildings at WTC indicates official foreknowledge and complicity, probably at the highest levels. | Medium (Griffin, 2004, 2005; Hufschmid, 2002; Paul & Hoffman, 2004; Tarpley, 2005) |

| Anthrax letter attacks. 2001. PLANNED INTERNATIONAL EVENT | Bush popularity rises; defense spending increases; Republicans gain in off-year elections; military invasion of Afghanistan; pretext for invasion of Iraq. CONTROL WAR POLICY | Officially blamed on Bruce Ivins but more likely part of the overall 9/11 operation. The anthrax has been traced to a strain developed by the U.S. Army. Circumstantial evidence of cover-up. | High for involvement of U.S. bio-weapons expert(s)

|

| Assassination of Senator Paul Wellstone. 2002. ASSASSINATION | Republicans regain control of the Senate after Wellstone’s replacement. CONTROL WAR POLICY | Intelligence operatives. | Low |

| Iraq-gate. 2003. MANIPULATION OF DEFENSE INFO/POLICY | U.S. gains control of Iraq oil production; Iran surrounded by U.S. armies; other Mid-East nations intimidated. CONTROL WAR POLICY | President Bush, Vice President Cheney, CIA Director fix intelligence to justify war. Bush misrepresents intelligence to Congress in State of Union address. CIA officer Valerie Plame is outed in an attempt to discredit Joseph Wilson. | High (Clark, 2004; Dean, 2004; Wilson, 2004; Woodward, 2004) |

| Bogus terror alerts in advance of 2004 election. 2004. MANIPULATION OF DEFENSE INFO/POLICY | Bush wins reelection and support is maintained for the war on terror. POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM | Terror alerts to rally support for the President going into the 2004 presidential election. | High (Hall, 2005) |

| Ohio’s disputed 2004 presidential election. 2004. ELECTION TAMPERING | Bush wins electoral college vote with a 118,000 vote margin in Ohio. POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM | Republican election officials impede voting in Democratic precincts. | High (Miller, 2005; Tarpley, 2005) |

When we stop looking at SCADs one-by-one, and we telescope out and look at them collectively or, so to speak, “from above,” we see a nation repeatedly abused. This abuse is another reason for the citizenry’s incident-specific myopia; trauma fragments memory because traumatic events loom too large to be kept in perspective. Just as victims of child abuse and spouse abuse tend to have fragmented recollections of the abuse, America’s collective memory of assassinations, defense failures, and other shocking events — the people’s shared narrative and sense of history — is shattered into emotionally charged but disconnected bits and pieces.

SCAD patterns. For the purpose of illustrating the SCAD construct, I will focus on the patterns in Table 4-1 that are readily apparent.

- Many SCADs are associated with foreign policy and international conflict. Such SCADs include the Gulf of Tonkin incident; the burglary of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office; the 1968 October Surprise; Iran-Contra; 9/11; the anthrax letter attacks; fake intelligence leading to the war in Iraq; the bogus terror alerts in 2004; and the assassinations of John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy. All of these SCADs contributed to the initiation or continuation of military conflicts.

- SCADs are fairly limited in their modus operandi (MO). SCAD-MOs listed by order of frequency are assassinations (6), mass deceptions manipulating defense information or policy (6), planned international-conflict events (3), election tampering (2), and burglaries (2). With the possible exception of election tampering, all of these MOs are indicative of groups with expertise in the skills of espionage and covert, paramilitary operations.

- Many SCADs in the post-WWII era indicate direct and nested connections to two presidents: Richard Nixon and George W. Bush. Nixon was not only responsible for Watergate and the illegal surveillance of Daniel Ellsberg, he alone benefitted from all three of the suspicious attacks on political candidates in the 1960s and 1970s: the assassinations of John Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy, and the attempted assassination of George Wallace. If JFK and RFK had not been killed, Nixon would not have been elected president in 1968, and if Wallace had not been shot, Nixon might not have been reelected in 1972. The SCADs that benefitted Bush include the election-administration problems in Florida in 2000 and in Ohio in 2004; the events of 9/11; the anthrax letter attacks on top Senate Democrats in October 2001; Iraq-gate; and the series of specious terror alerts that rallied support for Bush before the 2004 presidential election.

- The range of officials targeted for assassination in the post-WWII era is limited to those most directly associated with foreign policy: presidents (and presidential candidates) and senators. Most other high-ranking officials in the federal government have seldom been murdered even though many have attracted widespread hostility and opposition. No Vice Presidents have been assassinated, nor have any justices of the U.S. Supreme Court. The only member of the U.S. House of Representatives who has been targeted is Gabrielle Giffords in January 2011. If lone gunmen have been roaming the country in search of political victims, it is difficult to understand why they have not struck more widely, especially given that most officials receive no Secret Service protection. Why did no assassins go after Joe McCarthy when he became notorious for his accusations about communists, or Earle Warren after the Supreme Court’s decisions requiring school desegregation, or Spiro Agnew after he attacked the motives of antiwar protestors, or Janet Reno after she authorized the FBI’s raid on the Branch Dividians in Waco? If one assassination of a top public official were committed each year, and if targets were randomly selected, the odds of a president being killed in any given year would be 1 in 546. (There are 100 senators, 435 representatives, 9 Supreme Court justices, 1 vice president, and 1 president.) The odds of two presidents (Kennedy and Reagan) being shot by chance since 1948 are roughly 1 in 274,000. If Robert Kennedy is included (as a president-to-be), the odds of three presidents being targeted by chance since 1948 are approximately 1 in 149 million.

- The same is also true of senators. Three senators have been confirmed to have been targeted for assassination since 1948: Robert Kennedy, Patrick Leahy, and Tom Daschle. If one assassination of a top public official were committed each year, and if targets were randomly selected, the odds of a senator being targeted in any given year would be 1 in 5.46 (or 100/546). However, the odds of three senators being targeted by chance over this time period are approximately 1 in 5 million. But of course senators are not being selected at random. Senators have been assassinated only when either running for president (Robert Kennedy) or when the Senate was closely divided and the death of a single senator from the majority party could significantly impact policy. Aside from RFK, the only well confirmed senatorial assassinations or attempted assassinations in the post-WWII era occurred in 2001 when Democrats controlled the Senate by virtue of a one-vote advantage over Republicans. In May of 2001, just four months after George W. Bush gained the presidency in a SCAD-ridden disputed election, Republican Jim Jeffords left the party to become an independent, and the Senate shifted to Democratic control for the first time since 1994. Five months later, on 9 October 2001, letters laced with anthrax were used in an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate two leading Senate Democrats, Majority Leader Tom Daschle and Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy. The anthrax in the letters came from what is known as the “Ames strain,” which was developed and distributed to biomedical research laboratories by the U.S. Army (Tarpley, 2005, pp. 311–318).

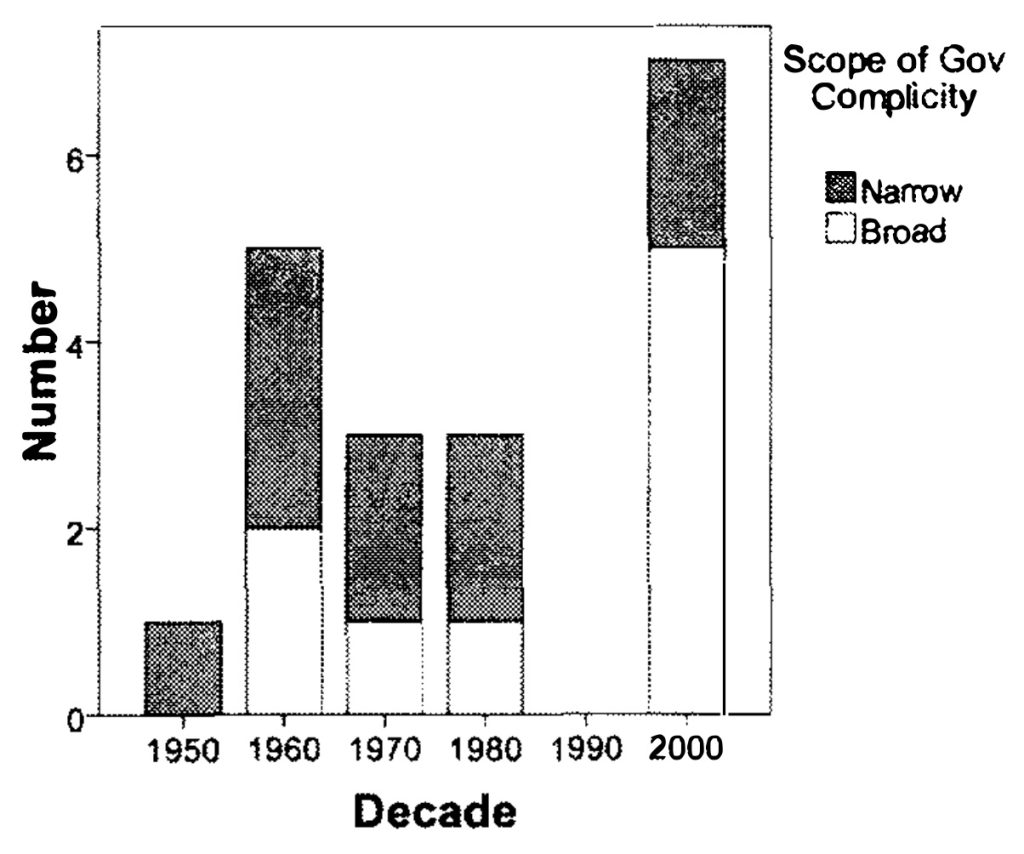

- Ominously, the frequency of SCADs recently increased sharply, and the scope of government complicity has been growing wider. Figure 1 (below) is a bar graph of the frequency of SCADs by decade. SCAD frequency surged in the 1960s, declined in the 1970s and 1980s, dropped to zero when the Cold War ended in the 1990s, but then jumped dramatically in the 2000s. To some extent, the SCAD sprees of the 1960s and the 2000s reflected the criminality associated with Presidents Nixon and George W. Bush. However, the widening scope of government complicity across the decades suggests creeping corruption may be amplifying the untoward implications of criminally inclined presidential administrations.

The expanding scope of government complicity in elite political criminality can be observed in the trajectory from Watergate through Iran-Contra to Iraq-gate (cf., Bernstein, 1976). The crimes of the Nixon Administration were driven by the President’s personal fears and animosities, and involved only a handful of top officials, most of whom participated only in cover-ups and, even then, reluctantly. Furthermore, Republican and Democratic members of Congress joined together to investigate and condemn the President’s actions. In contrast, the Iran-Contra episode was systemic, organized, and carefully planned, and its investigation was impeded by partisan opposition even though (or perhaps because) it obviously appeared connected to the alleged 1980 October Surprise. Motivated by ideology, Iran-Contra emanated from the White House and garnered enthusiastic participation by high-ranking officials and career professionals within the State Department, the CIA, and the military. Even wider in scope and more deeply woven into governing institutions were the crimes apparently committed by the Bush-Cheney Administration (Conyers, 2007; Fisher, 2004; Goldsmith, 2007; Goodman, 2007; Greenwald, 2007; Loo and Philips, 2006; Wolf, 2007). Attacking the organs of deliberation, policymaking, oversight and legal review, they appear to have involved officials throughout the executive branch and perhaps leaders in Congress as well.

Figure 4-1: SCAD Frequency and Scope of Government Complicity

Observations about 9/11

Presented below are some suggestions for future research and investigation. These suggestions are speculative in nature and, ultimately, may fail to bear empirical fruit. They are offered in the spirit of scientific curiosity and exploration, recognizing that science advances by making novel discoveries, not by veering clear of untraveled ground.

The SCAD heuristic. A potential heuristic for 9/11 research is to think in terms of what SCADs in general imply about the likely characteristics of 9/11 tactics, perpetrators, concealment, and so on. In a sense, this involves using SCAD patterns as a scope or template for searching through 9/11 evidence.

So what is seen when 9/11 is observed through a “SCAD scope”? First, of course, we see that 9/11 possesses many characteristics that have been observed in other SCADs and suspected SCADs in the post-World War II era. Table 2 lists SCAD characteristics, gives examples of SCADs that have those characteristics, and indicates how each factor is reflected in 9/11. In addition to 9/11, two or more SCADs or suspected SCADs in the table have the following traits: involved overlapping considerations of presidential politics and foreign policy; fomented militarism or cleared the way for wars or the continuation of wars; employed the skills and tactics of covert operations and psychological warfare; had crime scenes that were investigated superficially and cleaned up quickly; had incriminating photographic or documentary evidence that was either sequestered or ignored; garnered tendentious analyses by officials to explain away anomalous forensic evidence; plagued by “coincidences” that contributed to their success and concealment; occurred in pairs or clusters close in time; and have been associated with cognitive infiltration or other efforts by officials to deflect popular suspicions.

Table 4-2: 9/11 SCAD Characteristics

| SCAD Characteristic | Examples | 9/11 Parallels |

| SCADs often appear where presidential politics and foreign policy intersect | Gulf of Tonkin incident and Congressional Resolution; The crimes of Watergate; the October Surprises of 1968 and 1980 | 9/11 put to rest questions about the disputed 2000 presidential election and rallied popular support around the President George W. Bush. |

| SCADs frequently foment or clear the way for wars or the continuation of wars | The Gulf of Tonkin incident, the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King; the 1968 October Surprise; | 9/11 and the anthrax letter attacks were the pretext for wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and for a policy of preemptive war. The anthrax letter attacks supported fears of Iraqi WMD |

| SCADs often employ the skills and tactics of covert operations and psychological warfare | Watergate wiretapping, Iran-Contra “cutouts,” and forged documents on Iraqi acquisition of uranium | 9/11 used airplanes as weapons and involved controlled demolition; |

| SCAD crime scenes are investigated superficially and are cleaned up quickly | President Kennedy’s limousine was washed at Parkland Hospital; a doorframe riddled with bullets when Robert Kennedy was assassinated was “lost” by the Los Angeles Police Department | Debris from the WTC was cleaned up quickly and steel was shipped to China. NIST conducted no tests for signs of explosives and incendiaries |

| Incriminating photographic or documentary evidence is either sequestered or ignored | The Zapruder film was immediately purchased by Look Magazine; Iran-Contra documents were shredded by Oliver North; Howard Hunt’s safe in the White House was cleaned out; the hard drives on Katherine Harris’ computers were erased. | Videos from security cameras around the Pentagon were confiscated and withheld; videos of WTC collapses were not considered by NIST; photographs taken from a helicopter flying above WTC were sequestered until Feb. 2010. |

| Tendentious technical analyses are developed to explain away anomalous forensic evidence or frame favored suspect

| In JFK assassination investigation, magic bullet theory developed to explain how JFK was wounded twice and John Connolly was wounded by two shots. After 2000 election, Florida appointed a commission that blamed the election fiasco on “voter error” and punch-card ballots, overlooking evidence of crimes and partisan intrigue. | NIST theory of the pancake collapse of the Twin Towers and the key-beam collapse of WTC7 (all based on computer simulation ignoring visual evidence). Silicon in mailed anthrax attributed to water used in growing (but unable to replicate when challenged by Congress). Anthrax traced by DNA to batch under control of Bruce Ivins (later rejected by NSF review).

|

| Lines of Inquiry Suggested by SCAD Patterns | ||

| SCADs are plagued by suspicious “coincidences” – consequences benefitting certain officials, inexplicable breaches of procedure, administrative failures, investigative gaps, witness deaths, lost or destroyed evidence, etc. | JFK assassination: Nixon in Dallas that morning; limo route changed to include sharp turn at Texas School Book Depository; JFK limo washed at hospital; Oswald killed. 2000, 2004 elections: Results differ inexplicably from exit polls and in Bush’s favor; insufficient staff & equipment at precincts where Democrats are concentrated; ballot design flaws favoring Bush. | All hijackers slip through airport screening; Confusion caused by war games; President sits in Florida classroom after second plane hits WTC towers; Three steel skyscrapers collapse at near free-fall acceleration into their own footprints; Larry Silverstein says he decided to “pull” WTC Building 7; Anthrax from US domestic lab mailed one week after 9/11. See Table 3 for more items. |

| SCADs usually occur in clusters and clustered SCADs have similarities or connections that point to likely suspects | The assassination of John Kennedy was followed by the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald while in police custody by a police-connected mobster; the attacks on Daniel Ellsberg were followed by Watergate and a multitude of “dirty tricks” to influence the Democratic primaries. | The 9/11 hijackings were followed by the anthrax letter attacks. Guilty knowledge indicated by White House being administered Cipro while Congressional leaders and the public were not warned

Plame-gate/Iraq-gate |

| Cognitive infiltration is employed by public officials to subliminally deflect public suspicions and otherwise shape public perceptions of the SCAD | The term “conspiracy theory” was planted to stigmatize criticism of the Warren Commission report. Two days after the arrest at the Watergate, Nixon Press Secretary Ron Ziegler famously dismissed the crime as a “third-rate burglary attempt” (quoted in Ripley 1973). Whereas the crime was actually political espionage, election tampering, and wiretapping, to this day it is referred to as the Watergate burglary. | The term 9/11 exaggerates the threat of terrorism, limits the scope of investigation, and subliminally excites fear and foments social panic; also, withholding photographs taken from a helicopter flying above WTC impeded conceptualization of the destruction “from above.” |

Research on 9/11 has documented in detail all of the SCAD characteristics listed in Table 4-2 with the exception of those in the bottom three rows. The SCAD scope or template highlights these neglected factors and points to potentially promising lines of inquiry and analysis. Investigators should consider: (1) Estimating the statistical probability of 9/11’s many “coincidences”; (2) Examining the actions of Bush, Cheney, and other Administration officials for signs of complicity not just in 9/11 but also in other crimes and suspicious events closely related to 9/11 in time, tactics, or consequences; and (3) Studying the communicative implications, origins, and diffusion of 9/11 terminology for signs of cognitive infiltration and “meme seeding.”

The improbability of 9/11. 9/11 stands out from other SCADs and suspected SCADs in the range of “coincidences” surrounding it that indicate official complicity. Table 4-3 expands on the examples listed in Table 4-2 (third row from the bottom). Those who accept the official account of 9/11 must attribute virtually all of these coincidental occurrences to chance. Doing so amounts to embracing a “coincidence theory” of 9/11 that defies scientific reasoning.

Table 4-3: The “Coincidence Theory” of 9/11

(in which all of the following factors are dismissed as unrelated, unintentional, or random occurrences)

| Before the Attacks

| During the Attacks

| Immediate Effects and Aftermath

| Related to the Investigation

|

| Project for a New American Century says military buildup needed but not possible without a “new Pearl Harbor”

DOD project Able Danger identifies 4 of the future hijackers as part of an al Qaeda cell a year before 9/11. The Able Danger data are destroyed by order of DOD before 9/11. | All hijackers slip through airport screening

Air traffic controllers think hijackings may be part of war games President sits in Florida classroom after being informed of second plane hitting WTC towers Hijacked plane en route to DC is tracked for ~ 20 minutes but is not intercepted Cheney appears to give order not to intercept plane headed to DC | Three steel skyscrapers collapse at near free-fall acceleration into their own footprints

Videos show what appears to be molten steel Pools of molten steel reported during cleanup Larry Silverstein says he decided to “pull” WTC Building 7 Cleanup workers assured WTC is safe despite dust and fumes Anthrax from US domestic lab mailed one week after 9/11 | Terrorists identified within 24 hours

Next day, Bush tells Richard Clarke to look for connections between 9/11 and Iraq Bin Laden denies involvement in 9/11 US rejects offer by Taliban to turn over bin Laden if there is evidence he sponsored 9/11 WTC not tested for evidence of explosives or incendiaries Steel at the site cut up quickly and shipped to China |

| Before the Attacks

| During the Attacks

| Immediate Effects and Aftermath

| Related to the Investigation

|

| US envoys meet with Taliban in summer 2001 and threaten war if a pipeline is not allowed to be built across Afghanistan

FBI field offices warn of Arabs seeking flight training but not training for takeoffs or landings FBI informant lives with one of the hijackers in California Cheney appointed to head an Energy Taskforce which examines oil reserves and contracts in the Middle East Cheney put in charge of war games In July 2001, a top CIA official meets with bin Laden in Dubai where the latter is being treated for kidney disease | White House receives call using codename for Air Force One and saying it is next target

Pentagon workers report huge explosion minutes before aircraft hits Firefighters report explosions in basement of towers Firefighters and others report explosions in Building 7 in the morning Cell phone calls said to be made from hijacked aircraft (later denied by FBI) Plane targeting Pentagon executes complex air maneuver that exceeds plane’s design capacity and most pilots’ skills Aircraft hits Pentagon on side under construction where deaths least likely | Anthrax sent to leading Democrats in the Senate

White House pressures FBI to link anthrax mailing to al Qaeda Hole in Pentagon appears too small for commercial jet Seismic record for collapses at WTC show seismic “spikes” at the beginning of the North Tower collapse, well before debris hits earth Tapes made by air traffic controllers during debriefing immediately after the attacks are destroyed BBC newscaster says Building 7 has collapsed before it actually collapses

| Editor of Fire Engineers magazine condemns investigation of WTC destruction a farce

CCT video tapes around Pentagon confiscated within an hour of the strike Bush and Cheney block an investigation for almost a year Bush, Cheney, Rice say an no one could have imagined hijacked airplanes being used as weapons Kissinger initially appointed Director of 9/11 Commission Zelikow appointed Director of 9/11 Commission despite conflicts of interest |

| Before the Attacks

| During the Attacks

| Immediate Effects and Aftermath

| Related to the Investigation

|

| In July, Attorney General Ashcroft stops flying on commercial airlines

War games are scheduled for 9/11/01, at least one of which involved hijacked aircraft In August, Presidential Daily Brief warns that bin Laden plans to strike in US, hijacked aircraft may be involved, mentions WTC Signs of insider trading on American and United Airlines stock shortly before 9/11 On Sept. 10, Pentagon officials cancel commercial air flights scheduled for 9/11 | Sec. of Defense Rumsfeld, 2nd in military chain of command after the President, wanders around outside the Pentagon after the aircraft hits

| Iowa State University destroys its comprehensive anthrax archives shortly after mailed anthrax is discovered, either at behest of or with approval of FBI

Photographs taken from a helicopter flying above WTC on 9/11 were sequestered until Feb. 2010 and were released only pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request. | 9/11 Commission not told terrorists’ “confessions” extracted with torture

9/11 Commission not allowed to see videotapes of interrogations CIA videotapes of waterboarding destroyed Building 7 not mentioned in 9/11 Commission Report Zelikow is informed of findings of Able Danger but does not include this in the 9/11 Commission Report

|

The science for estimating the likelihood of events occurring by chance is called statistics. In probability theory, events are assumed to have a finite range of variation. A flipped coin can land on only heads or tails. The probability of any given outcome occurring by chance is the proportion that outcome comprises of the total number of outcomes in the range of possible outcomes. The flipped coin landing on heads is one variant out of two; the other variant is tails. So the probability of a flipped coin landing on heads is one out of two, or 0.5.

Common sense tells us that the odds of a multiple events occurring together by chance are low, but the science of statistics can help us estimate how low. As the number of coincidences increases, the odds of them occurring by chance rapidly becomes infinitesimal, which is to say, almost impossible. The odds of one variant occurring twice are equal to the odds of it occurring once squared. The odds of getting two heads in two flips are one-in-four (.5 x .5 = .25). The odds of something occurring three times are the odds of it occurring once cubed. The odds of getting three heads in three flips are 1 in 8 (.5 x .5 x .5= .125). Ten heads out of ten flips would be expected to occur one time in 1,024 tries.

The number of “coincidences” in Table 4-3 exceeds 50. The odds of getting 50 heads in 50 flips are less than one in a quadrillion. This mathematical exercise does not apply directly to 9/11, but it does suggest that the odds of all the coincidences in Table 3 occurring together are astronomically small.

The anthrax letter attacks. SCAD research suggests SCADs are committed in pairs or clusters. Examples include the assassination of John Kennedy which was followed two days later by the assassination of Lee Harvey Oswald while in police custody; the stalking of Daniel Ellsberg which was followed by the crimes of Watergate and the attempted assassination of George Wallace; and the 1980 October Surprise which was followed by Iran-Contra. In the case of Watergate and Ellsberg, we know that the crimes in question had been committed by the same group, and that this group committed other crimes as well.

If this pattern holds for 9/11, then other crimes closely related in time or employing similar tactics were probably planned and organized by the same people. An obvious place to start looking for connections to 9/11 is with the anthrax letter attacks, but consideration should also be given to investigating other events and venues, including: who decided to withhold the photos taken of the WTC on 9/11 from a helicopter flying overhead; who forged the documents indicating (falsely) that Iraq had purchased yellowcake uranium from Niger; after the U.S invasion of Iraq, who authorized payments to a former Iraqi official for forging a letter suggesting (falsely) the Iraqis possessed WMD but had moved them to another country; who authorized the expedited flights out of the U.S. for the relatives of Osama bin Laden; who initiated and arranged the meeting between envoys of the Bush-Cheney Administration and Taliban officials where war was threatened if the U.S. was not allowed to build a pipeline for transporting natural gas across Afghanistan. All of these questions remain unanswered.

Officially, the anthrax letter attacks have been attributed to Bruce Ivins, a bio-weapons expert who allegedly had psychological problems. However, the case against Ivins contains several gaps. The anthrax in the letters has not been conclusively connected to the anthrax in Ivins’ control; the high amount of silicon in the mailed anthrax, which enhanced its lethality, may have required equipment and skills Ivins lacked; and Ivins did not have direct control of the equipment allegedly used to dry the anthrax.

Like 9/11, the anthrax letter attacks played into the Bush-Cheney agenda for invading Iraq. In fact, the Administration immediately suggested that the anthrax came from Iraq. The effort to implicate the regime of Saddam Hussein was thwarted only because the FBI investigation concluded the anthrax came from a strain developed by the U.S. military at the Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, Maryland (Broad et al. 2001).

There is already circumstantial evidence in the public domain indicating the Bush-Cheney Administration had foreknowledge of the anthrax letter attacks. In the evening on 9/11, weeks before the anthrax mailings were discovered, medical officers at the White House distributed a powerful antibiotic (Cipro) to the president and other officials (Sobieraj 2001). Officials might claim that Cipro was administered simply as a precaution, but this innocent explanation is belied by the failure of anyone in the White House to tell Congress and the public that an anthrax attack was feared. Investigators should determine what kind of anthrax attack was feared; who issued the warning; who suggested that Cipro should be administered; to whom Cipro was given and for how long; and why other officials and the public were not warned. Those officials who were responsible for these decisions, especially those earliest in the decision chain, should be considered suspect of complicity in both 9/11 and the anthrax letter attacks, and their whereabouts and contacts on and immediately before and after 9/11, should be carefully tracked.

Linguistic thought control. The possibility of linguistic thought control in relation to 9/11, the anthrax letter attacks, and other associated crimes, should be investigated. If any destructive memes were surreptitiously injected into public discourse, they may have characteristics similar to those of the conspiracy-theory label, which is normatively powerful but conceptually flawed and alien to America’s civic culture.

A number of memes have been introduced by the military as part of the war on terror, but they do not qualify as linguistic thought control because they were not released into the public sphere surreptitiously. Examples include: war on terror; extraordinary rendition; enhanced interrogation; detainee; collateral damage; evil doers; Islamofascism; and Operation Iraqi Freedom. These memes skew and hamper communication, but they are recognized as artificial constructs, and hence their ability to distort public discourse is mitigated.

In contrast, memes warranting inspection as possible plants for linguistic thought control are those that are taken for granted as natural products of sense-making in civil society. The most important example discussed here for purposes of illustration is the term “9/11.” If it was inserted into the organs of opinion formation during or immediately after the day of the hijackings, prior planning would probably have been necessary, which would be evidence of official complicity in the events of 9/11. Other examples of memes that warrant study include: ground zero, let’s roll, al Qaeda, lone wolf terrorist, and homegrown terrorist.

Today, the term “9/11” is accepted as simply a straightforward name for the events on September 11, 2001. However as a label for “terrorist attacks upon the United States” (the phrase used in the official title of the 9/11 Commission) 9/11 has characteristics of a conceptual Trojan horse similar to those of the conspiracy-theory meme. On the surface, the term 9/11 says almost nothing; it is not even a complete date. And yet it carries hidden associations and implications that reverberate in the national psyche.

First, the term 9/11 contains emotionally charged symbolism. The numbers 9-1-1 correspond to the phone number used to contact first responders when emergencies occur in the United States. This means references to 9/11 subliminally provoke thoughts among Americans about picking up the phone and calling for an ambulance or for help from police or firefighters. The 9/11 label would not have been possible if the events had not occurred on September 11; this itself suggests prior planning for a date with emotional connections. Nevertheless, state intervention into the discursive processes of civil society would have been necessary both to suggest the date as the label for the events and to drop the year from “9-11-01.”

As a matter of fact, the connection between the abbreviated date (9/11) and the emergency phone number (9-1-1) was highlighted in what had to be one of the very first times the term 9/11 was used in the media. The 9/11 label was included in the headline of a story in the New York Times on September 12, 2001. The headline was “America’s Emergency Line: 9/11.” The first sentence of the article referred to “America’s aptly dated wake-up call.” Since then, the connection between the date and the emergency number has been mentioned in the New York Times only one other time — in an article published in February 2002. The author of the first article was Bill Keller, a senior writer who had served previously as chief of the Moscow Bureau during the years when the Soviet Union was collapsing. Keller was appointed Executive Editor of the New York Times in 2003 and was in that position when the Times withheld the story about the Bush-Cheney Administration’s warrantless wiretapping until after the 2004 presidential election. Keller should be considered a “person of interest” in any legal investigation of the events of 9/11.

A second characteristic of the 9/11 label indicative of cognitive infiltration is that it deviates from America’s naming conventions for the type of event it designates. With the possible exception of Independence Day, which is often referred to as July fourth, the 9/11 label marks the first time Americans have called a historic event by an abbreviated form of the date on which the event occurred. 9/11 is a first-of-its-kind “numeric acronym.” Americans do not call Pearl Harbor “12/7,” even though President Roosevelt declared December 7, 1941, to be “a date that will live in infamy.” Americans do not refer to the JFK assassination as “11/22.” Historically, as these examples suggest, Americans have referred to crimes, tragedies, and disasters by their targets, locations, methods, or effects — not their dates. Americans remember the Alamo and the sinking of the Maine. They speak of Three Mile Island, Hurricane Katrina, the Oklahoma City bombing, and Watergate.

If Americans had followed this pattern for 9/11, the events would have been called something else. The hijackings. The attack on America. The airplane terror attack. Americans would tell themselves to remember the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

Even when Americans want to refer to a specific day because of its historical significance, they seldom use the date. They speak of Independence Day, D-Day, VE Day, Election Day, etc. If they had done this for September 11, it would have been called the Day of Terror or something like that.

Third, the term 9/11 should be suspected of being an artifact of linguistic thought control because the term shapes perceptions in ways that play into elite agendas for global military aggression. In drawing attention to a date as opposed to the method or location of the destruction, the term 9/11 suggests there has been a shift in the flow of history. 9/11 is an historical marker. There is the world before 9/11, and the world after 9/11. As Vice President Cheney and other officials said, “9/11 changed everything.” Clearly, this framing suggests the need for a dramatic U.S. response and a determined, hardened attitude. Think how less convincing and urgent it would be to say the hijackings changed everything, or the collapse of the Twin Towers and Building 7 changed everything. When you refer to hijackings and buildings, you cannot avoid the realization that the threat of terrorism is in no way comparable to the threat the allies faced in World War II or to the dangers in the standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union in the Cold War. Using the term “9/11” to refer to the destruction at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon has the effect of exaggerating the threat posed by people who hijack airplanes and use them as weapons.

Fourth, by stressing the date, the term 9/11 draws our attention away from the victims, the destruction, and the military response. Imagine if we referred to the events in question as the Airplane Mass Murders, or the Multiple Skyscraper Collapse, or the National Air-Defense Failure. Each of these names points to a different investigative focus. 9/11, as a name, causes us to think in terms of chronology and historic change instead of failures and culpability.

We should not be surprised that intelligence elites might develop and plant concepts in public discourse. It is very unlikely the conspiracy-theory label was a unique instance of CIA concept-creation and deployment. Recall the language used to sell the Iraq War. Could Bush, Cheney or Rice come up with the line, “We don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud”? Would they have known to reach back to World War II for their nomenclature, or to think of words and phrases like “Homeland Security,” “Axis of Evil,” “ground zero,” and the like? Such word-craft requires teams of people, historical research, linguistic analysis, advertising specialists, experts in propaganda, and more.

Recognize, too, that if officials were complicit in the events of 9/11, which ample evidence suggests, they would have been intensely concerned with how the 9/11 events were interpreted and perceived. Hence they would have been especially interested in what the events would eventually be called. The RAND Corporation, a CIA-connected think tank, began studying this phenomenon in the 1950s. Roberta Wohlstetter, wife of RAND game-theorist and nuclear-war strategist Albert Wohlstetter, examined the communicative context of Pearl Harbor, including how the attack came to be understood and referenced in popular culture, and how its meaning evolved. The parts of her study that were not classified were published as Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision. Paul Wolfowitz, a student of Roberta’s, cited this book when he appeared before Congress shortly after 9/11. Also, the topic of how historic events are popularly understood and conceptualized is reputed to be an area of expertise of Phillip Zelikow, the director of the 9/11 Commission and primary author of the Bush-Cheney Administration’s first policy statement on preemptive war. Thus officials had both the motive and the capability to frame the events of September 11, 2001, as “9/11,” and their extensive network of media assets gave them the means.

Fortunately, if the 9/11 meme is indeed an artifact of linguistic thought control, it should be possible to track the meme back to its source. The media record is still largely intact in the archives of the nation’s major newspapers and television networks. Moreover, the length of time that would need to be covered is fairly short: a few weeks at most. Once the originating sources and conveyors are identified, they could be interviewed to determine their role in propagating the label.

Conclusion

The main theme emerging from the foregoing analysis is that SCADs appear to be surface indications of a deeper, invisible level of politics in which officials at the highest levels of government use deception, conspiracy, and violence to shape national policies and priorities. This manipulation of domestic politics is an extension of America’s duplicity in foreign affairs and draws on the nation’s well-developed skills in covert operations. Through their experience with covert actions, national security agencies have developed a wide range of skills and tactics for subverting and overthrowing regimes, manipulating international tensions, and disrupting ideological movements. Apparently, these skills are being used domestically as well as overseas.

On rare occasions when policymakers have been called to justify domestic covert operations and other deceptions, they have done so by asserting that public opinion, both domestic and international, is a critical battlefront in conflicts between democratic capitalism and its ideological and military opponents. Although the implications of this policy for popular control of government are seldom examined, the policy itself was and is no secret. As an assistant secretary of defense said in response to claims that public opinion had been manipulated during the Cuban missile crisis, “News generated by actions of the government as to content and timing are part of the arsenal of weaponry that a President has in application of military force and related forces to the solution of political problems, or to the application of international political pressure” (Wise and Ross, 1964, pp. 297-298). Richard Nixon put it more bluntly. In claiming that the president has the power to break the law when protecting national security, he said: “Well, when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal” (Frost, 1977).

References

- Arrows, F. & Fetzer, J. (2004). American assassination: The strange death of Senator Paul Wellstone. Brooklyn: Vox Pop.

- Ahmed, N.F. (2005). The war on truth: 9/11, disinformation, and the anatomy of terrorism. Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press.

- Bacevich, A. J. (2005). The new American militarism: How Americans are seduced by war. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Barstow, D. (2008). Message machine: Behind analysts, the Pentagon’s hidden hand. The New York Times, April 20, p.1.

- Barstow, D. & Van Natta Jr., D. (2001). How Bush took Florida: Mining the overseas absentee vote. The New York Times. July 15.

- Beard, C.A., & Beard, M.R. (1927). The rise of American civilization. New York: The MacMillan Company.

- Bernstein, C. & Woodward, B. (1974). All the president’s men. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Black, W. K..(2005). The best way to rob a bank is to own one. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Blum, W. K. (2004). Killing hope: U.S. military and C.I.A interventions since World War II. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press.

- Bowen, R.S. (1991). The immaculate deception: The Bush crime family exposed. Chicago: Global Insights.

- Broad, W. J., Johnston, D., Miller, J., & Zielbauer, P. (2001). Anthrax probe hampered by FBI blunders. The New York Times, November 9.

- Calavita, K., Pontell, H., & Tillman, R. (1999). Big money crime: Fraud and politics in the savings and loan crisis.

- Clarke, R. A. (2004). Against all enemies: Inside America’s war on terror. New York: The Free Press.

- Dahl, R. & Lindblom, C. E. (1976). Politics, Economics, and Welfare. New Haven: Yale, 1946.

- Dean, J. W. (2004). Worse than Watergate: The secret presidency of George W. Bush. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

- Dean, J. W. (2007). Broken government: How Republican rule destroyed the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. New York: Viking.

- deHaven-Smith, L. (2005). The Battle for Florida. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- deHaven-Smith, L. (2006). “When political crimes are inside jobs: Detecting State Crimes Against Democracy,” Administrative Theory & Praxis, Vol. 28: No. 3. (September), pp. 330-355.

- deHaven-Smith, L., 2010. Beyond conspiracy theory: Patterns of high crime in American government. American Behavioral Scientist, 53 6), 795–825.

- deHaven-Smith, L. and Witt, M., 2009. Preventing state crimes against democracy. Administration & Society, 41(5), 527–550.

- Douglass, J. W. (2003). Interview with Donald Wilson, in DiEugenio, J. and Pease, L., Eds., The Assassinations (479–491). Los Angeles: Feral House.

- Douglass, J. W. (2008). JFK and the unspeakable: Why he died and why it matters. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books.

- Eisenhower (1961). Farewell Address, available online from the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum at http://www.eisenhower.archives.gov.

- Ellsberg, D. (2002). Secrets: A memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. London: Penguin Press.

- Fetzer, J. H. (2000). Smoking guns and the death of JFK. In J. H. Fetzer (Ed.). Murder in Dealey Plaza: What we know that we didn’t know then about the death of JFK (pp. 1–16). Chicago: Catfeet Press.

- Fisher, L. (2004). The way we go to war: The Iraq Resolution, in Gregg, G.L. and Rozell, M.J., eds., Considering the Bush Presidency (107–124). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ford, G. R. (1974). Proclamation 4311, granting a pardon to Richard Nixon. Available online at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum, at http://www.ford.utexas.edu.

- Frost, D. (1977). The third Nixon–Frost interview. The New York Times, May 20, p. A16.

- Garrison, J. (1988). On the trail of the assassins: My investigation and prosecution of the murder of President Kennedy. New York: Sheridan Square Press.

- Goldsmith, J. (2007). The terror presidency: Law and judgment inside the Bush Administration. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Goodman, M.A. (2008). The failure of intelligence: The decline and fall of the CIA. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Gray, L. P. (2008). In Nixon’s web: A year in the crosshairs of Watergate. New York: Henry Holt.

- Greenwald, G. (2007). A tragic legacy: How a good vs. evil mentality destroyed the Bush presidency. New York: Crown Publishing.

- Griffin, D. R. (2004). The new Pearl Harbor: Disturbing questions about the Bush administration and 9/11. Northampton, Massachusetts: Olive Branch Press.

- Griffin, D. R. (2005). The 9/11 Commission Report: Omissions and Distortions. Northampton, Massachusetts: Olive Branch Press.

- Griffin, R. P. (1950). Constitutional law: Corporations: Artificial ‘persons’ and the Fourteenth Amendment. Michigan Law Review, 48(7), 983–993.

- Groden, R. J. (1993). The Killing of a president: The complete photographic record of the JFK assassination, the conspiracy, and the cover-up. New York: Penguin Books USA.

- Haldeman, H. R. (1978). The ends of power. New York: Times Books.

- Hall, M. (2005). Ridge reveals clashes on alerts. USA Today, May 10.

- Hedegaard, E. (2007). The Last Confession of E. Howard Hunt, Rolling Stone, April 5, 2007.

- Hedges, C. (2008). American fascists: The Christian right and the war on America. London: Vintage Books.

- Hellinger,D. (2003). Paranoia, conspiracy and hegemony in American politics. In H.G. West H.G. & T. Sanders (Eds.), Transparency and conspiracy: Ethnographies of suspicion in the new world order (pp. 204–232): Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hoover, J. E, (1958). Masters of deceit: The story of Communism in America and how to fight it. New York: Henry Holt.