The Disease

The term “anthrax” refers primarily to a disease.[1] But the term is also used to refer to the bacterium that causes the disease. There is, therefore, ambiguity in the expression, “anthrax attacks.” The larger aim of the senders of the letters was to induce, or threaten to induce, the disease, but it is also true that spores of the bacterium were contained in some of the letters.

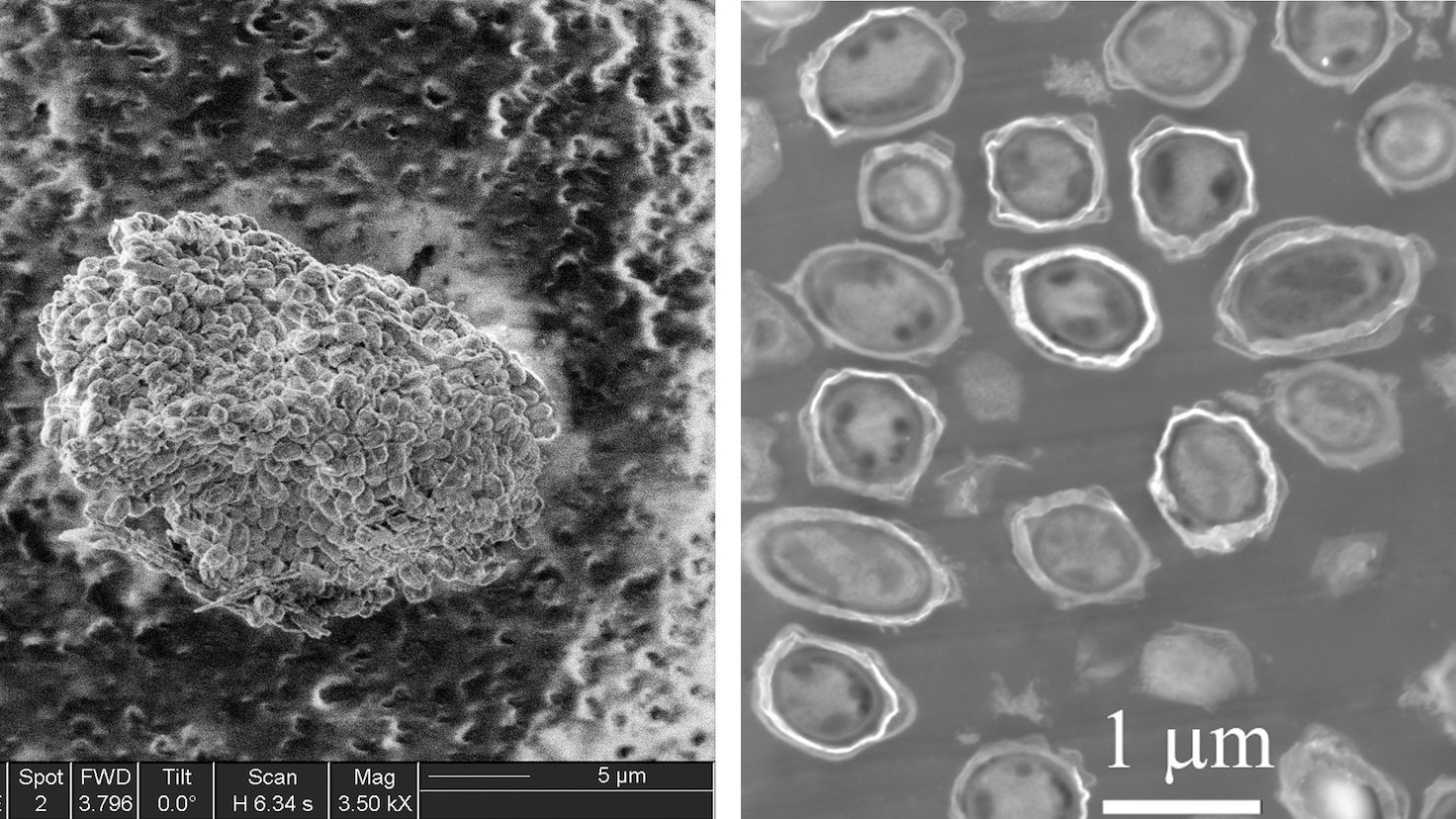

Like all bacteria, Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) is a single-celled microorganism. B. anthracis is also, however, a parasitic bacterium, meaning that it thrives on other life forms. B. anthracis has two main states, an active state, in which it can take in nutrients and reproduce, and a state of dormancy, in which there is no perceptible metabolic activity. Cells of the dormant form are referred to as “spores” or “endospores.” The DNA inside the spore is protected from its environment by several layers of coating.

Spores of the genus Bacillus are among the hardiest type of cell that exists. Some are capable of surviving for thousands of years through drought and temperature extremes. The bacterium enters into this state of dormancy when nutrients are scarce, at which time the spores develop, through a complex, multi-phase process, within the vegetative cells and then separate themselves.

B. anthracis is found in the soil and in the bodies of animals, especially herbivores. Human beings, in natural conditions, generally take in spores indirectly via contact with animals. Since the spores are tough and can survive for long periods in the soil without water or nutrients, it is not easy to rid the soil of them. They remain ready to germinate when conditions are favorable—for example, within the body of a warm-blooded creature.

As a disease that afflicts human beings, anthrax takes three forms depending on the means by which the bacterium enters the body. If it enters through a cut in the skin, cutaneous anthrax results. The great majority of those who develop anthrax get this form of the disease. Swelling at the site of entry will eventually result in a black scab, from which the disease gets its name (“anthrax” is the Greek word for coal). Without treatment, about 20% of those who develop cutaneous anthrax will die; but it is easy to treat this form of the disease with antibiotics and in the modern period lethality rates are low. If the spores are ingested—for example, by eating undercooked meat containing anthrax spores—the result will be gastrointestinal anthrax, which has a much higher mortality rate than the cutaneous form. Finally, if the spores are breathed in the result is inhalation (or pulmonary) anthrax, which is the most lethal form of the disease: estimates of the lethality rate vary from 75% to 95%. All deaths in the 2001 attacks were the result of inhalation anthrax. That the rate of death was lower than normal in the 2001 attacks was probably due to widespread awareness of the disease (including foreknowledge and corresponding preparations) as well as prompt and intense treatment of people discovered to be infected.

In all forms of the disease antibiotics are crucial to treatment. The aim of antibiotics, after all, is to kill or impede the action of bacteria. But it is not the bacterium per se that is lethal but the toxins produced by the bacterium. If the victim’s condition is not properly diagnosed and promptly treated—especially in the case of inhalation anthrax—even killing the bacteria with antibiotics will not stop the toxins from wreaking havoc on the body’s organs.

When the inhalation form of the disease is first contracted symptoms are “flu-like:” sore throat, tiredness, mild fever, and so on. As the disease progresses the symptoms become more pronounced and may include difficulty in breathing, high fever, meningitis (swelling of the spinal cord and brain) and shock, followed by coma and death.

The Weapon

There is a long and sordid history of people deliberately inducing disease in other human beings through the introduction of bacteria, especially in the context of war and conquest. Many of the most devastating cases are pre-modern and involved such crude methods as hurling diseased corpses over walls.[2]

Because of its pathogenic nature and its ability to form durable spores, B. anthracis is a natural choice for those wishing to have a biological weapon. It has been developed as a weapon by nations over the last hundred years. [3]

Attempts were made by Germany in WWI to attack enemy livestock with anthrax bacteria.4 Several other nations have produced and stored B. anthracis, though few have actually deployed it.

Although proponents of the Global War on Terror have devoted considerable energy to portraying the use of anthrax as “unthinkable” and as radically evil,[5] associating anthrax research and production with past adversaries of the United States such as the Soviet Union and Iraq, the Western nations were leaders in the development of biological weapons. During WWII Germany was ahead of the Allies in the development of chemical warfare but the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada were collaborating in the development of biological weapons and were well ahead of the Axis powers.[6] Near the end of WWII the Allies were in a position to launch a major anthrax attack on Germany. One plan involved dropping anthrax-infected cattle cakes to destroy beef and dairy herds, thus denying the German population major sources of food, while also dropping anthrax bombs on German cities to induce inhalation anthrax in humans. One estimate had these anthrax bombs taking the lives of three million people, most of them civilians.[7] Fortunately, although the weapons had been stockpiled and the delivery systems were in place, the attack was finally judged unnecessary. Germany’s decision not to employ chemical and biological weapons directly against Allied forces and homelands was one factor in Allied restraint.[8] In addition, it was decided that if Germany could be brought to her knees without using these controversial weapons the Allies would be saved from condemnation by the many who found biological warfare repugnant.

The U.K. was the leader in anthrax research at the beginning of WWII but the U.S. led the way by the end, using its new Camp Detrick and Dugway testing ground. U.S. scientists quickly discovered how to produce large quantities of the bacterium, how to disperse it effectively (for example, through the use of aerosol bombs), and how to produce increasingly lethal subtypes of the bacterium.[9]

After WWII anthrax research and development continued, especially among the Cold War superpowers. The Soviet Union apparently retained a large and active program until the disintegration of the state.[10] In the U.S., Richard Nixon announced the termination of the U.S. biological program in 1969, putting faith instead in the U.S. nuclear arsenal. From that point on anthrax weapon development in the U.S. was curtailed and, to the extent that it survived, was forced to go underground.

Aerosolizing anthrax—causing large numbers of spores to be dispersed and suspended in the air—remains one of the most intensely studied, and most intensely feared, methods of biological warfare. It was central, both as a reality and as fiction, to the events of 2001.

Conventions and Acts

After WWI an initiative was mounted to ban the use of biological weapons, resulting in the Geneva Protocol of 1925. Its full name is “Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare.”[11] The U.S. was an early signatory but did not ratify the agreement until 1975.

The Geneva Protocol was an extension of earlier international agreements. It proclaims simply that the use of such weapons and methods is prohibited. It does not cover the development, stockpiling and sharing of such agents and methods.

In 1972 a new agreement, intended to remedy this deficiency, was presented to the world. Its common name is the “Biological Weapons Convention” (BWC), while its full name is “Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction.”[12] The BWC entered into force in 1975. It referred to, and built upon, the Geneva Protocol but carried the offensive against biological weapons to a new level by attempting to prohibit not merely their use but all necessary stages prior to deployment. The BWC makes it clear that the context of the agreement is the move toward “complete and general disarmament” and, especially, the “elimination of all types of weapons of mass destruction.” The Convention explicitly seeks “to exclude completely the possibility of bacteriological (biological) agents and toxins being used as weapons.”

One of the common complaints against international law is that it is too vague in what it prohibits and that it lacks adequate mechanisms for inspection and enforcement. The BWC was an attempt to answer these objections by inching closer to an efficient, workable method of putting the ideals of the Geneva Protocol into effect.

In the 1980s some Americans were angry to learn that while government rhetoric had been blaming its enemies (Vietnam and the Soviet Union especially) for their research, and alleged deployment, of biological weapons, the U.S. itself was carrying out work that violated the BWC.[13] One of these critics was Harvard-trained international law expert, Professor Francis A. Boyle. Subsequently, Boyle himself was asked to draft the BWC’s domestic enabling legislation.[14] The “Biological Weapons Anti-Terrorism Act of 1989” was adopted unanimously by both chambers of Congress, and George H. W. Bush signed it into law on May 22, 1990.[15]

Boyle has said that while he was willing to have the Act named as if it were directed against “Third World crazies” if that would make it palatable to Congress, his primary targets were actually the “crazies” in the U.S. military and intelligence communities.[16]

In 1995 participants from many countries began meeting to work out how to add verification procedures to the historic initiative to eliminate bio-weapons. The Protocol they worked out would have, they believed, provided transparency and made cheating much more difficult than it then was. The proposed agreement included on-site inspections of states that were parties to the BWC. On July 25, 2001, with international negotiations in high gear, the U.S. representative announced that the U.S. would not support the Protocol, implying that although the U.S. was trustworthy, other signatories were not and would continue to hide their biological weapons facilities. Although the U.S. was the only party to the Convention that did not support the Protocol, its support was considered crucial and the negotiations collapsed.[17]

The rejection of the Protocol by the George W. Bush administration was merely one result, among many, of that administration’s strategy of weakening international law. The Protocol, of course, would also have made life much more difficult for anyone wishing to carry out the sort of anthrax attacks that occurred within the U.S. in the fall of 2001.

The Attacks

The anthrax attacks of 2001 began in September, shortly after the events of 9/11. [18] Victims of the attacks were identified between October 3 and November 20. At least 22 people were thought to have become infected, 11 with cutaneous anthrax and 11 with inhalation anthrax. All instances of the disease appear to have been caused by letters containing dried spores of the bacteria sent through the public mail. Two of those who died were postal workers.

The five people known to have died from anthrax (all from the inhalation form of the disease) were Robert Stevens, a Florida photo editor (died Oct. 5); Thomas Morris Jr., a postal worker at a mail sorting facility in Washington, D.C. (died Oct. 21); Joseph Curseen Jr., a postal worker at the same facility as Thomas Morris Jr. (died Oct. 22); Kathy Nguyen, a hospital employee in New York City (died Oct. 31); and Ottilie Lundgren, an elderly woman living in a small town in Connecticut (died Nov. 21).

The first letters to be recovered containing spores of B. anthracis were postmarked on September 18 in Princeton, New Jersey. Letters apparently sent at this time went to the following media corporations: NBC News, the New York Post, CBS News, ABC News, and the Sun (or possibly its sister publication, the National Enquirer). Infections were induced in all of these places. During this same period bio-threat letters containing messages and powder but no genuine anthrax were also sent to news media.

Beginning on approximately September 22, skin lesions began to develop in one or more persons at each of these news locations, but the illness was not yet diagnosed as anthrax.[19] Robert Stevens’ illness was the first to be correctly diagnosed. Stevens was admitted to the hospital with an undiagnosed illness on October 2. His disease was diagnosed as anthrax on October 3 and a press conference was held announcing this on October 4. He died on October 5. Robert Stevens is exceptionally important in the history of the anthrax attacks not only because he was the first to die of the disease but also because no one, in the public or even the U.S. intelligence community, is supposed to have known that B. anthracis was in play before his diagnosis. That is, according to the FBI, no one except the perpetrators knew before Oct. 3, 2001 that the attacks were in progress. This date is important to keep in mind.

At some point between October 6 and October 8, letters containing a more highly refined and lethal preparation of B. anthracis were sent to Democratic Senators Thomas Daschle and Patrick Leahy.

Daschle’s letter was opened and studied by the FBI on October 15. This single letter contaminated the Hart Senate Building, leading to the closure of the building and to numerous confirmed anthrax exposures. The Leahy letter was buried in mail that was sequestered after the discovery of the Daschle letter, so it was not discovered for some time.

The official U.S. government position immediately after the death of Stevens was that there was no evidence his death was part of a terrorist attack. However, the FBI soon opened a criminal investigation, and gradually the hypothesis became widespread that the attacks were the second blow in a “one-two punch” delivered by terrorists, the first blow having been the attacks of 9/11.

The “one-two punch” hypothesis is one among several that will be considered in the following chapters.

Notes to Chapter 2

- The brief description here is based on: Burke Cunha, “Anthrax,” Medscape, n.d., http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/212127-overview; R. C. Spencer, “Bacillus Anthracis,” Journal of Clinical Pathology 56(2003): 182–87; Jesse Emspak, “How Anthrax Kills: Toxins Damage Liver and Heart,” Livescience, August 28, 2013, http://www.livescience. com/39251-anthrax-kills-toxins-liver-heart.html.

- Stefan Riedel, “Biological Warfare and Bioterrorism: A Historical Review,” Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 17 (4) (October 2004): 400–406.

- My description is based on a critical reading of: John Bryden, Deadly Allies: Canada’s Secret War, 1937-1947 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1989); Jeanne Guillemin, Biological Weapons: From the Invention of State-Sponsored Programs to Contemporary Bioterrorism (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 2005); Judith Miller, Stephen Engelberg, and William Broad, Germs: Biological Weapons and America’s Secret War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001); Milton Leitenberg, “Biological Weapons: Where Have We Come from over the Past 100 Years?,” Public Interest Report: Journal of the Federation of American Scientists 64, no. 3 (December 2011), http://www.fas.org/pubs/pir/article/bioweapons. html.

- Guillemin, Biological Weapons: From the Invention of State-Sponsored Programs to Contemporary Bioterrorism, 21.

- See Chapter 8.

- Bryden, Deadly Allies: Canada’s Secret War, 1937-1947.

- Guillemin, Biological Weapons: From the Invention of State-Sponsored Programs to Contemporary Bioterrorism, 69.

- Bryden, Deadly Allies: Canada’s Secret War, 1937-1947.

- Guillemin, Biological Weapons: From the Invention of State-Sponsored Programs to Contemporary Bioterrorism, 67 ff.

- Ibid., 131 ff.

- Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or Other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, 1925, http://www.un.org/disarmament/WMD/Bio/pdf/Status_Protocol.pdf.

- Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction, 1972, http://disarmament.un.org/treaties/t/bwc/ text.

- Francis Boyle, Biowarfare and Terrorism (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2005).

- Biological Weapons Anti-Terrorism Act of 1989, 1990, http://thomas. loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c101:S.993.ENR:.

- Boyle, Biowarfare and Terrorism.

- Ibid.

- Rebecca Whitehair and Seth Brugger, “BWC Protocol Talks in Geneva Collapse Following U.S. Rejection,” Arms Control Association, September 2001, https://www.armscontrol.org/print/900. For a somewhat different perspective, see Jonathan Tucker, “Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) Compliance Protocol,” NTI (Nuclear Threat Initiative), Aug. 1, 2001. http://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/biological-weapons-convention-bwc/

- Information in this summary can be found in standard works on the anthrax attacks such as Leonard Cole, The Anthrax Letters: A Bioterrorism Expert Investigates the Attacks That Shocked America (Skyhorse Publishing, 2009); Jeanne Guillemin, American Anthrax: Fear, Crime, and the Investigation of the Nation’s Deadliest Bioterror Attack (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2011); “History Commons: 2001 Anthrax Attacks.”

- “History Commons: 2001 Anthrax Attacks,” September 22-October 2, 2001: Some People Get Sick from Anthrax, but Are Not Properly Diagnosed.