Introduction

Major crisis events, such as the assassination of political leaders, terrorist attacks and public health emergencies, can be politically useful. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 helped the Roosevelt administration bring the US into WWII. The Reichstag fire in 1933 provided Hitler with the opportunity to suppress political opposition in Germany and paved the way for the rise of fascism. Unfortunately, critical discussion of whether such events are exploited or even instigated in order to enable particular policy agendas is all too often dismissed as ‘conspiracism’. This has been the case with both 9/11 and COVID-19 (the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2), both of which are argued by some to have been manipulated for political purposes. In the case of the former, some claim that the al-Qaeda attacks on New York and Washington were, in fact, a ‘false flag’ or ‘manufactured war trigger’, designed to enable military action in countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq. In the case of the latter, some argue, for example, that COVID-19 served to enable the ‘Great Reset’ political agenda. Meaningful discussion of these matters in mainstream settings is, however, nearly always suppressed by the pejorative use of the term ‘conspiracy theory’, which implies irrational, poorly evidenced, even pathological, argumentation. Even relatively limited criticism regarding the likely effectiveness of ‘lockdown’ policy in relation to COVID-19 by Oxford epidemiologist Sunetra Gupta was aggressively dismissed as ‘conspiracy theory’.

Fortunately, Peter Dale Scott’s structural deep event (SDE) and Lance deHaven-Smith’s state crime against democracy (SCAD) are concepts that provide a basis for critical exploration of major crisis events. This article builds upon these ideas, as well as that of propaganda and preliminary work by Kevin Ryan (2020), in order to develop a framework for identifying the key features, or ‘observable implications’, of a structural deep event. Utilizing the principles of a ‘structured focused comparison’ (George, 1979), the framework is then applied across two events — 9/11 and COVID-19 — claimed to have been manipulated for political purposes. This approach enables a conceptually grounded and empirically systematic analysis of these events and, in this study, provides a preliminary assessment, or ‘plausibility probe’ (Levy, 2008), of the hypothesis that both were structural deep events involving manipulation and nefarious intent.

The argument proceeds as follows. Section one briefly discusses the role of conspiracy and agency with respect to explaining political phenomena. Section two introduces the SDE and SCAD concepts, noting in particular their relationship to propaganda, before setting out the key features of an SDE and defining its observable implications. Section two draws in part upon preliminary work by Kevin Ryan (2020a&b). Sections three and four present empirical evidence from 9/11 and COVID-19. It will be argued that both events share key features associated with SDEs — a) major policy drives associated with structural transformation of society, b) involvement of deep state actors, and c) the manipulation of an event and public perceptions of it — and that further research is warranted into these events. The paper concludes by discussing key implications of this study and makes suggestions for further research.

Section One: Crises, conspiracies and agency

Crises, particularly those associated with shocking and dramatic events, are politically useful. The 15th/16th century arch strategist Niccolò Machiavelli is often credited with the invention of the phrase ‘never let a crisis go to waste’ whilst 20th century political actors, ranging from Winston Churchill to Saul Alinsky, are frequently credited with having used the phrase. US economist Milton Friedman stated: ‘[o]nly a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas lying around’ (1982, p. ix). In the popular book The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein describes how ‘[f]or three decades, Friedman and his followers had methodically exploited moments of shock in other countries’ (2007: 12). In 2009, as fears surrounding a potential Swine Flu pandemic emerged, Jacques Attali (2009), former adviser to French President Mitterrand, stated:

History teaches us that humanity only evolves significantly when it is truly afraid: it first sets up defense mechanisms; sometimes intolerable (scapegoats and totalitarianisms); sometimes futile (distractions); sometimes effective (therapies, setting aside if necessary all previous moral principles). Then, once the crisis is over, it transforms these mechanisms to make them compatible with individual freedom, and to include them in a democratic health policy. The pandemic that is beginning could trigger one of those structuring fears.

Another truism is that political actors seek to both control events and manage public perceptions of them. In 2004, as events unfolded following the invasion of Iraq in 2003, a senior Bush advisor, widely believed to be Karl Rove, stated:

[People like you journalists/intellectuals] believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality. That’s not the way the world really works anymore. We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study, too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.

— Senior Bush Advisor, quoted on background in the New York Times Magazine, October 17, 2004 (Suskind, 2004)

The utilization of crisis events can be understood as a form of propaganda, sometimes referred to as ‘propaganda of the deed’ (Jowett and O’Donnell, 2012: 301), in which a real-world event is instigated or exploited for propagandistic purposes.

Unfortunately, sustained academic engagement with researching and understanding these truisms has been, to a very large extent, thwarted by drives to discredit their investigation. According to Rankin (2017), the pejorative use of the term ‘conspiracy theory’ has been encouraged through interventions by Karl Popper (1945), Richard Hofstadter (1964) and the CIA (1967). These have served to intimidate and discourage serious examination of nefarious and covert intentional actions by political actors (Ellefritz, 2022a&b). The study of propaganda has at times suffered academic censorship based on similar grounds; for example, Noam Chomsky, in his critiques of media bias and Western imperialism, has been ‘routinely labelled a conspiracy theorist’ (Herring and Robinson, 2003: p. 553). Other delimiting tendencies across the social sciences include a propensity to privilege the study of structure over agency, and an under-developed understanding how ideologies are formed and maintained. In the case of the former, analytical attention is taken away from purposeful and intentional actions by individuals and groups of individuals. In the case of the latter, ideology is too often conceived of as a self-generating and free-floating phenomenon when, in fact, it emerges from ‘the actions of real people in the (would-be) secret (but sometimes discoverable) low conspiracies which are a continuous and inevitable part of capitalist rule; in censorship, spin, lobbying, public relations, marketing, and advertising’ (Miller, 2002).

But, as has been detailed at length, such drives are not defendable on intellectual grounds (Hayward, 2021) and, as Parenti (1993/2020) explains:

No ruling class could survive if it wasn’t attentive to its own interests; consciously trying to anticipate, control or initiate events at home and abroad both overtly and secretly. It is hard to imagine a modern state if there would be no conspiracy, no plans, no machinations, deceptions or secrecy within the circles of power. In the United States there have been conspiracies aplenty … they are all now a matter of public record. (Welch and Parenti, 1993/2020)

In short, agency and intentionality are relevant to understanding the world around us.

Two conceptual approaches, the structural deep event (SDE) developed by Peter Dale Scott, and the State Crimes Against Democracy (SCAD) idea from Lance DeHaven-Smith, together provide an entry point for understanding and identifying phenomena involving the strategic and organised manipulation of events by political elites.

Section Two: Conceptual lenses; Structural Deep Events (SDEs), State Crimes Against Democracy (SCADs) and Propaganda

Structural Deep Events (SDEs)

Scott’s ‘structural deep event’ (SDE) concept refers to the instigation or exploitation of a real-world event by powerful actors, ones both internal and external to a state’s formal governance structures, in order to advance political-economic agendas that have structural implications for society. He describes SDEs as ‘mysterious events, like the JFK assassination, the Watergate break-in, or 9/11, which violate the American social structure, have a major impact on American society, repeatedly involve lawbreaking or violence, and in many cases proceed from an unknown dark force’ (Scott, 2015). Scott distinguishes structural deep events from mid and low-level deep events that do not ‘affect the whole fabric of society’ (Scott, 2015). Developing and complementing Scott’s work with the concept of ‘apex crimes’, criminologist de Lint describes these as events of ‘paradigm or norm-changing significance’ (de Lint, 2020: p. 1158). Also, although Scott is sometimes hesitant to attribute SDEs to intentional actions — ‘I am not attributing them all to a single manipulative “secret team” and ‘I see them as flowing from the workings of repressive power itself (Scott, 2011: p. 4) — the examples he gives, such as the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, do plausibly involve deliberate and strategic actions by individuals or groups of individuals. Indeed, elsewhere Scott acknowledges that SDEs involve intentionality: He approvingly quotes Operation Gladio operative Vincenzo Vinciguerra’s description of ‘dark forces’ in Italy ‘with capacity of giving a strategic direction to the outrages’ (Scott, 2012: p. 2).2

The ideas of the deep state and deep politics are central to the SDE concept and refer to hidden or opaque practices, arrangements and actors that operate within, or exert an influence upon, a state’s governance apparatus. The idea of the ‘deep state’ lacks agreed definition (Good, 2022: p. 144) and sometimes is referred to as the national security state, the administrative state, or the military-industrial complex. Developing his concept of the tripartite state, Good usefully distinguishes between the legitimate democratic state, the security state and the deep state, with the latter being an ‘outgrowth of the overworld of private wealth’ (Good, 2008).3 Actors involved with deep politics can include both legitimate ones, such as the intelligence services, and illegitimate ones, like organized crime. For example, regarding the latter, Scott’s (1993) first book on deep politics, Deep Politics and the Death of JFK, discussed the use of the mafia by the US government in order to counter communism in post-World War II Italy, whilst his 2010 book, The American War Machine, documents CIA connections with illegal drug trafficking. Also included are legitimate actors who carry out illegitimate or illegal actions such as those seen during Watergate controversy when US President Nixon authorized break-ins as a part of an attempt to counter his political rivals (Sheehan, 1971). Scott also recognizes the role and importance of private corporations and financial actors as potential participants in SDEs, noting in particular the high volume of outsourced intelligence and military activities as well as the influence of Wall Street and its associated think tank the Council of Foreign Relations (CFR). Above and beyond the state, transnational and supranational power elite networks (Philips, 2018) also play a role in SDEs including with respect to their financing, according to Scott. Kevin Ryan has noted (Ryan 2013a) the importance, during the 1970s and 80s, of the Safari Club and the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI).

Because the deep state functions out of public view, its existence runs counter to the requirements of a healthy, well-functioning, democracy. Indeed, the deep state and deep politics are, if nothing else, ‘anti-democratic and opaque’ (Good, 2022: p. 145). Also, as Scott notes, ‘the bottom-upward processes of democracy have been increasingly supplanted by the top-downward processes of the deep state’ (Scott, 2015). Scott also sees the increasing prevalence of deep politics in the US as a function of its status as an imperial power:

I hope to describe certain impersonal governing laws that determine the socio-dynamics of all large-scale societies (often called empires) that deploy their surplus of power to expand beyond their own borders and force their will on other peoples. This process of expansion generates predictable trends of behavior in the institutions of all such societies, and also in the individuals competing for advancement in those institutions. In America it has converted the military-industrial complex from a threat at the margins of the established civil order, to a pervasive force dominating the order. (Scott, 2011: pp. 1-2)

State Crimes Against Democracy (SCADs)

The SCAD concept is often discussed in association with SDEs. The idea was devised by Lance deHaven-Smith (2006) in order to ‘move beyond the debilitating, slipshod, and scattershot speculation of conspiracy theories by focusing inquiry on patterns in elite political criminality that reveal systemic weaknesses, institutional rivalries, and illicit networks’ (deHaven-Smith, 2010: p. 796). A SCAD is defined as ‘actions or inactions by government insiders intended to manipulate democratic processes and undermine popular sovereignty’ (deHaven-Smith, 2009: p. 527). Notable SCADs, according to DeHaven-Smith, include the well-known Watergate controversy during the 1970s, mentioned above, and the Iran-Contra scandal of the 1980s. deHaven-Smith argues that SCADs have become progressively worse and more prevalent because of the ‘relatively recent formation of political-economic “complexes” with the means and motivation to manipulate the national political agenda’ (deHaven-Smith and Witt, 2009: p. 529). In definitional terms, SCADs include a wide range of political malfeasance, stretching from ‘election tampering’ through to illegal ‘secret wars’ and includes actions by ‘public officials to subvert popular control of government … even if they are not technically in violation of established laws’ (deHaven-Smith and Witt, 2009: p. 548: emphasis added).

In relation to SDEs, the SCAD concept is useful because it can be drawn upon in order to identify them more clearly as types of events that involve criminal activity and that usurp democratic processes. In particular, the SCAD concept’s focus on criminality helps add clarity to the idea that what we are concerned here with is deliberate and intentional wrongdoing by powerful actors: as noted above, Scott is at times hesitant to attribute SDEs to intentional actions and the SCAD concept contributes toward overcoming this fuzziness.

The terms, however, are not synonymous. SCADs as described by de Haven-Smith are limited to criminal, or criminal-like, actions carried out by state actors and can involve ‘policies’, as well as ‘events’, which do not necessarily have structural implications. Also, whilst all SDEs involve covert activity and deception, some SCADs are overt. For example, the responses to the 2008 banking crisis, which involved the bailing out the banks and the printing trillions of dollars, were not hidden but could still be argued to be a crime against democracy, or at the very least, an offense against democracy. Most importantly, and as described above, SDEs can potentially involve a wide array of both state and non-state actors, including transnational or supranational elite networks, and involve both events and deceptions. Accordingly, we present SCADs and SDEs as overlapping phenomena all of which fall under the category of crimes or offences against democracy (CADs) (see Figure One below).

Figure One: Conceptualising SCADs, SDEs and CADs

SDEs and Propaganda

Propaganda involves organized attempts to influence the beliefs and conduct of people. Although frequently referred to via a range of euphemisms — such as strategic communication, public relations, psychological operations and advertising — and sometimes considered to be alien to contemporary liberal democracies (Robinson, 2019), propaganda is in fact widely practiced across the West. In most contemporary definitions, propaganda is understood as a manipulative form of persuasion and one that works against an individual’s free will (Robinson et al, 2018). As such, and as set out by Bakir et al (2019), propaganda is a non-consensual persuasion process and typically works through forms of deception — such as lying, exaggeration, omission, and misdirection — as well through incentivization and coercion (Bakir et al, 2019). Furthermore, although usually associated with words and images, propaganda can also operate via action in the real world, through the so-called ‘propaganda of the deed’, whereby actions are undertaken with a view to influencing thoughts, attitudes and behaviour. For example, the infamous ‘shock and awe’ campaign initiated at the start of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 included the bombing of high-profile government targets in Baghdad. The buildings were empty and of little value in military terms, but their widely publicized destruction was designed to send a powerful signal to the Iraq people that resistance was futile.

SDEs can be understood as a form of propaganda in a number of ways. They are, first and foremost, strategic moves based upon real world action — propaganda of the deed — aimed at influencing beliefs and conduct. They also involve deception, a key propaganda tactic, with ‘systematic falsifications in media and internal government records’ (Scott, 2011). And, in the largest sense, SDEs represent attempts to control the direction of society against the consent and wishes of the people by shifting power upwards to create a ‘social system dominated from above rather than governed from below’ (Scott, 2011: p. 4). As such, because SDEs involve strategic attempts to organize the compliance of a population, via deceptive and undemocratic means, with structurally significant political and economic agendas, they can be understood as a type of propaganda.

Synthesis: Defining an SDE and operationalizing its observable implications

Drawing together these ideas, we can define an SDE as a propagandistic type of CAD in which a network, involving either or both deep state and non-state actors, instigates or exploits a real-world event in order to advance, in a deceptive and anti-democratic manner, a society altering political/economic agenda. Building upon this definition, the observable implications of an SDE can be defined and operationalized as follows (see also Table One below):

Structural-level policies (the ‘why’ question)

An SDE involves an attempt to advance a major policy that has structural implications for society. These policies will be largely hidden from view in that their existence and objectives are not clearly stated and will be obscured by deceptive propaganda narratives promoted by authorities. For example, in the case of the JFK assassination, it is argued by some that his murder, deceptively presented as the work of a lone gunman, enabled the maintenance of the Cold War and escalation in Vietnam (Douglas, 2008). More generally, Ryan (2020, a&b) notes the importance of identifying policies that increase state control whilst reducing civil liberties, impact negatively on wealth distribution, and which do more harm than good. Determining in any given case whether such ‘hidden’ structural-level policies exist can also be understood as part of addressing the ‘why’ question.

Deep politics actors (the ‘who’ question)

An SDE necessarily involves actors who are operating covertly. This can include elected politicians, officials from the intelligence services, and non-state actors including both criminal networks and those from supranational governance and corporate entities. Whoever these actors are, and from wherever they are situated within political power structures, the key question is whether they are involved in covert and undemocratic activity. As Ryan (2020, a&b) points out, one can often observe clear conflicts of interest across various actors involved with structural deep events. So, for example, during the Iran-Contra deep event US government officials worked with intelligence operatives and the corporate world in order to illegally sell weapons to Iran and, in turn, supply financial aid to the Contra terrorist group in Nicaragua. Determining in any given case whether such deep actors are present can be understood as part of addressing the ‘who’ question.

Manipulation of an event (the ‘what’ question)

Central to the SDE concept is the idea that an event is instigated or exploited. The first aspect of event manipulation involves the rapid reaction by authorities whereby, with only minimal investigation (De-Haven Smith, 2012), a problem is identified (Scott, 2015), responsibility attributed (de Lint, 2020: p. 1158), and the necessary solution then presented to the public. As Entman (1991) describes, in relation to the political ‘framing’ of media reporting, defining a problem, its causes, making moral judgements, and the prescribing of policy remedies, are central components of narrative building. Second, maintaining the official presentation of what happened during the event necessitates manipulation of science & official investigations. This occurs through the use and abuse of scientific and other trusted institutions (Ryan, 2023) which might involve manipulated investigations, fraudulent scientific claims (Ryan, 2020 a&b); 2021), incriminating evidence being sequestered or ignored (De-Haven Smith, 2012), as well as the issuing of demonstrably fraudulent reports. Third, maintaining public belief in the official narrative demands propaganda and the promotion of official claims through major communication platforms such as mainstream media (de Lint, 2020: p. 1159). Propaganda will result in the one-sided promotion of official claims, often via incessant fear-based media coverage (Ryan 2023, Altheide 2018) and presentation of an elusive, all-powerful enemy (Ryan 2020, a&b). It will also result in aggressive suppression of dissident voices through techniques including smear campaigns and cognitive infiltration (De-Haven Smith, 2012). Fourth, an SDE is likely to be accompanied by evidence of foreknowledge & planning. Put simply, this means individuals knowing that a crisis event is about to occur when, according to the official narrative, they should have no idea whatsoever. For example, and as Ryan (2020, a&b) notes, SDEs are often preceded by training exercises that mimic the event that is about to occur. Determining the presence of these features is part of addressing the ‘what’ question.

Table One: Key elements of an SDE and their observable implications

| Key Elements | Observable Implications (some of which are apparent in real-time) | |

| A S T R U C T U R A L | An event that is instigated or exploited in order to pursue specific political/economic agenda. | Major policy drives with structural consequences for politics, economics and societies (Scott, 2015; de Lint, 2020) Major policy drives that increase state control and reduce individual liberties i.e. threaten democracy (Ryan 2020, a&b) Major policy drives impacting (negatively) wealth distribution (Ryan 2020, a&b) A policy that causes more harm than the alleged threat, i.e. appears irrational (Ryan, 2020 a&b) |

| B D E E P | Involvement of deep actors including intelligence services, organized crime and supranational-level actors | Intelligence agency control of information Hidden intelligence backgrounds of culprits (Scott, 2015) The protection by the FBI and CIA of the designated culprits before the events to ensure they would not be stopped (Scott, 2015) Involvement of corporations, NGOs, think tanks foundations, global governance institutions, finance institutions Demonstrable conflicts of interest/co-optation (Ryan 2020 a&b) |

| C E V E N T | Manipulation or use of an event itself: instigation or exploitation and with deception involved | C1 Rapid actions in response with minimal investigation of initial events (de Lint, 2020) Crime scenes investigated only superficially (De-Haven Smith, 2012: de Lint, 2020)) Instant identification of designated culprits (Scott, 2015: de Lint, 2020)) |

| E V E N T | C2 Manipulation of science & official investigations An abuse of scientific and other trusted institutions (Ryan, 2023) Manipulated investigation/scientific claims (Ryan, 2020; 2021) Tendentious technical analyses developed to explain away anomalies in forensic evidence (De-Haven Smith, 2012) Incriminating evidence is sequestered or ignored (De-Haven Smith, 2012) Demonstrably false official reports | |

| E V E N T | C3 Propaganda: promotion of official claims Propaganda: suppression of questioning. One-sided coverage framed in terms of accepting official premises, debate bounded (de Lint, 2020). Cognitive infiltration is employed to subliminally deflect public suspicions (De-Haven Smith, 2012) Censorship of dissent Incessant fear-based media coverage (Ryan 2023, Altheide 2018) An elusive, all-powerful enemy (Ryan 2020 a&b) | |

| E V E N T | C4 Foreknowledge & Planning Foreknowledge of an event Scenario gaming and planning; Preceded by exercises mimicking the threat (Ryan, 2020 a&b) Predictive Programming Insider trading |

Research Approach

This framework, grounded in the SDE concept, can be used in order to draw descriptive inferences regarding a purported SDE: If the features are present in any given case, confidence is increased that it is an SDE.4 The approach is transparent and reproducible, thus allowing for scrutiny by other researchers. Furthermore, and as part of a structured, focused comparison (George, 1979), these key features (observable implications) can be searched across multiple cases and thereby contribute to the ‘orderly, cumulative development of knowledge and theory about the phenomenon in question’ (George, 1979: p. 70).

In this paper, we apply the framework to 9/11 and COVID-19 as part of a preliminary exploration of evidence, sometimes described as a ‘plausibility probe’ (Levy, 2008), based upon analysis of both primary and secondary sources, in order to determine whether there is sufficiently strong evidence regarding the specified SDE features to warrant further confirmatory research.

Section Three: Examining 9/11 for evidence of structural deep event indicators

The official narrative regarding 9/11, as described by the 9/11 Commission Report (2004), was that on the 11th of September 2001 a Sunni-based, fundamentalist terror organisation called al-Qaeda conspired and carried out a major terrorist attack against the US involving the hijacking of civilian airliners and the targeting of civilian and military buildings. The attacks led to the total destruction of three skyscrapers in New York — World Trade Center buildings 1, 2 and 7 — damage to the Pentagon, and killed almost 3,000 people. The terrorists were purported to have been motivated by religious zeal and political grievance. The ‘global war on terror’ was the declared policy response and purported to be aimed at eradicating the threat posed by Islamic fundamentalist terrorism and included military action in and against countries accused of harboring such groups, as well as civil liberty restrictions at home. It is estimated that almost 5 million have been killed during this ‘war’ — over 940,000 people died directly due to war violence whilst 3.6-3.8 million died indirectly (Watson Institute, 2024).

A) Evidence of structural-level agendas

With respect to 9/11, there is evidence of a pre-existing agenda and subsequent foreign policy relating to the violent overthrow of ‘enemy regimes’. During the 1990s a neo-conservative think tank called the Project for the New American Century (PNAC) was formed. It included individuals who were to become key players in the Bush administration, including the future vice president Dick Cheney. This think tank was committed to extending US dominance into the 21st century through aggressive US unilateralism. Writing in the context of the realist-liberal debate over humanitarian intervention (Robinson, 1999), PNAC member Robert Kagan described the need to maintain US hegemony through the use of its military. He wrote that ‘(m)ilitary strength alone will not avail . . . if we do not use it actively to maintain a world order which both supports and rests upon American hegemony’ (Kagan, 1996).

In 1998 a paper based upon a Stanford University report from the Working Group on Catastrophic Terrorism predicted nightmarish scenarios involving the release of a ‘deadly pathogen’, weapons of mass destruction including nuclear and chemical, and their use as part of a ‘catastrophic’ act of terrorism that would create a ‘watershed event in American History’ (Carter, Deutch and Zelikow, 1998: p. 81). One of its authors, Philip Zelikow, was later to lead the official investigation of 9/11 (hereafter the 9/11 Commission). In 2000, as Griffin (2017: p. 30) describes, PNAC published its Rebuilding America’s Defenses which stated that America’s grand strategy should be to use its military supremacy to establish an empire that includes the whole world. It also stated that the next US president ‘must increase military spending to preserve American geopolitical leadership’ (Griffin, 2017; p. 30). In calling for a revolution in military affairs in order to maintain US supremacy, the document also noted that, ‘absent some catastrophic and catalyzing event – like a new Pearl Harbor’ (PNAC, 2000: p. 51), these changes would be slow to emerge.

Specific plans to attack Afghanistan in order to overthrow its Taliban leadership predated 9/11 (Griffin, 2017: pp. 32-33; Guardian, 2004), as did the policy of regime-change in Iraq (Iraq Liberation Act, 1998). In addition, retired Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson (Former Chief of Staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell) states that plans to attack multiple countries were in place prior to 9/11 (Wilkerson, 2019). As we shall see in section 3a) below — a) Rapid actions in response with minimal investigation of initial events — plans to aggressively engage multiple countries became apparent almost as soon as the 9/11 event had occurred.

B) Evidence for the involvement of Deep Actors

A number of military special operations operatives played critical enabling roles related to the events of 9/11. These included Richard Armitage, the Deputy Secretary of State who had a history of overseeing special operations during and after the Vietnam War, including the 1970s CIA drug trafficking in Southeast Asia and the Iran-Contra crimes in the 1980s (Marshall, Scott and Hunter 1987). With regard to 9/11, Armitage instituted a new express visa program that provided visas to some of the alleged 9/11 hijackers and which allowed applicants to gain visas without providing verification of identity (Pound, 2001). Other 9/11 suspects linked to the Iran-Contra crimes include Barry McDaniel, the Chief Operating Officer of WTC security company Stratesec, and McDaniel’s former boss at The Carlyle Group, Frank Carlucci (Ryan 2013a). McDaniel’s new boss at Stratesec was Wirt D. Walker, whose career paralleled that of two known CIA operatives (Ryan, 2014).

Another US special operations soldier who played a crucial role at the WTC was Brian Michael Jenkins. Jenkins was seen as an architect of the contra war against Nicaragua, ‘a terror war aimed primarily at the civilian population and infrastructure’ (O’Sullivan, 1993). As deputy chairman of Crisis Management for Kroll Associates, Jenkins directed the response to the 1993 WTC bombing in terms of security upgrades. In this role, he reviewed the possibility of airliners crashing into the Twin Towers and implemented a plan for security of the WTC complex (Ryan, 2014).

The 9/11 Commission attributed the lack of air defenses on 9/11 to failures in communication between the FAA and the military. The key role in those communications was to have been played by the FAA’s hijack coordinator. The FAA hijack coordinator was Michael Canavan, a career special operations commander who had come to the civilian FAA job only nine months before 9/11. According to an FAA intelligence agent, one of the first things Canavan did in that job was lead and participate in exercises that were ‘pretty damn close to the 9/11 plot.’ Like a number of leaders in the US chain of command, Canavan went missing the morning of 9/11 and no one was assigned as his back-up. Canavan was never held responsible for his critical role, or even questioned about it (Ryan, 2014).

Whilst the official 9/11 narrative attributes responsibility for the events to Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda terror group, bin Laden was himself trained and funded by the CIA, and his brother was meeting with The Carlyle Group in Washington, D.C. on September 11, 2001 (Moran 2003).

Finally, Don Canestraro, a lead investigator for the legal body overseeing the cases of 9/11 defendants at Guantanamo Bay, conducted multiple interviews with high-ranking FBI and CIA officials related to Saudi government connections to the 9/11 attacks. Canestraro’s investigation found that at least two of the accused 9/11 hijackers had been recruited into a joint CIA-Saudi intelligence operation that was covered up at the highest levels (Klarenberg, 2023).

C) Evidence of event exploitation, instigation and deception

C1) Rapid actions in response accompanied by minimal investigation of the initial event

Problem definition, attribution of responsibility, and proposed solution were immediate in the case of 9/11. Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak, interviewed by the BBC’s Nick Gowing on BBC World during the morning of the attacks, stated responsibility would be known within 12 hours, demanded a ‘war on terror’ be launched, and identified Iran, Iraq, Libya and North Korea as ‘rogue states’ who sponsored terrorism. He also mentioned Osama bin Laden, the supposed leader of al-Qaeda (Barak, 2001). British Prime Minister Tony Blair, again on the day, described ‘mass terrorism’ as the new ‘evil’ perpetrated by ‘fanatics’ and called for the democracies of the world to come together to fight it (Blair, 2001). President Bush declared the US would ‘win the war against terrorism’ (Bush, 2001) and on the evening of 9/11 convened a ‘war council’ during which Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Sudan and Iran were identified by Secretary of State Donald Rumsfeld as countries that ‘might have harboured the attackers’ (9/11 Commission, 2004: p. 330). On the morning of September 12, NATO Secretary General George Robertson declared that ‘if it is determined that this attack was directed from abroad against the United States, it shall be regarded as an action covered by Article 5 of the Washington Treaty’ (Harrit, 2018). This declaration established the grounds for defining 9/11 as an attack on the whole of NATO, thus requiring a unified military response. On September 13, Secretary of State Rice chaired a Principals Committee meeting in order to ‘refine how the fight against al-Qaeda would be conducted (9/11 Commission, 2004: p. 331).

The initial focus on Afghanistan as phase one of the ‘war of terror’ was consolidated on October 2 when Frank Taylor, acting as the Ambassador from the US State Department, briefed the North Atlantic Council on the evidence purportedly linking bin Laden to the 9/11 event (Corbett, 2018; Harrit, 2018; Chossudovsky, 2023). The same day, according to Harrit (2018), a classified dispatch was sent by the US Statement Department to US representations worldwide titled ‘September 11: Working together to fight the plague of global terrorism and the case against al-Qa’ida’. The dispatch began with the instruction: ‘all addressees to brief senior host government officials on the information linking the Al-Qa’ida terrorist network’. As noted by Harrit (2018), a section of the dispatch was repeated verbatim by NATO Secretary General George Robertson in his speech following the Taylor briefing:

The facts are clear and compelling […] We know that the individuals who carried out these attacks were part of the world-wide terrorist network of Al-Qaida, headed by Osama bin Laden and his key lieutenants and protected by the Taliban. (Robertson cited in Harrit, 2018)

On October 4 2001, NATO invoked Article 5 and, by October 7, military action against Afghanistan was underway. According to Harrit, the classified dispatch contained ‘absolutely no forensic evidence in support of the claim that the 9/11 attacks were orchestrated from Afghanistan’. In the following years the FBI were to admit that there was ‘no hard evidence’ connecting bin Laden to 9/11, whilst The 9/11 Commission Report relied only on statements made by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed who had been subjected to torture (Griffin and Woodworth, 2018: pp. 160-161). As of 2024, Mohammed remains detained in Guantanamo Bay still awaiting trial.

Planning for the implementation of phase 2 of the ‘war on terror’ was also underway as soon as 9/11 had occurred. General Wesley Clark, former Supreme Allied Commander Europe of NATO 1997-2000, stated he became aware of a plan to attack multiple countries in the days following 9/11 (Clark 2007a, 2007b). He identified Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Iran as the countries targeted for ‘regime change’. As noted earlier, retired Colonel Lawrence Wilkerson (Former Chief of Staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell) states unequivocally that these plans to attack multiple countries were in place prior to 9/11 (Wilkerson 2019). The UK-based Chilcot Inquiry, which examined Britain’s involvement in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, reported a UK diplomatic cable, dated September 15 2001, as saying ‘[t]he “regime-change hawks” in Washington are arguing that a coalition put together for one purpose [against international terrorism] could be used to clear up other problems in the region’ (Chilcot 2016, 3.1: p. 65; p. 324). Also released via the Chilcot Inquiry, a December 2001 memo from UK Prime Minister Tony Blair to George Bush titled ‘The War Against Terrorism: The Second Phase’, discussed a total of seven countries (Iraq, Philippines, Syria, Iran, Yemen, Somalia and Indonesia) and provides further indications of how the ‘War on Terror’ was being conceived. For example, the memo stated: ‘If toppling Saddam is a prime objective, it is far easier to do it with Syria and Iran in favour or acquiescing rather than hitting all three at once’ (Blair, 2001a).

It is important to understand that many of these countries, particularly Iraq, Syria and Iran, could not have had any plausible relationship to a Sunni-based, fundamentalist terror organisation, which is what al-Qaeda was presented as. Syria and Iraq had secular political structures whilst Iran is predominantly Shia. The idea that these countries presented either legitimate or logical targets for a ‘war on terror’ based upon the official 9/11 narrative of Sunni terrorism represents a deception on the part of US and British politicians (Robinson, 2016).

C2) Manipulation of science and official investigations

As noted earlier, 9/11 involved the complete destruction World Trade Center (WTC) buildings 1, 2 (the Twin Towers) and 7 in New York. Buildings 1 and 2 had been hit by two aircraft but, being of their steel-frame construction, were not expected to collapse in entirety. Building 7 was not hit by any aircraft and yet suffered a global collapse late in the afternoon of 9/11. Historically, fire-induced total collapse of steel framed structures is highly unusual. Explaining these remarkable collapses became the focus of two investigations conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

The official account of the Twin Towers’ destruction was released in September of 2005. Unfortunately, NIST’s report provided only a hypothesis of the events leading up to the initiation of the collapses, or the ‘collapse initiation sequence’. NIST did not attempt to explain how, once the collapses initiated, the upper sections of these 110-story skyscrapers could continue falling downward through the path of greatest resistance. Instead, NIST simply asserted that, once collapse initiation began, ‘global collapse ensued’. With this statement, NIST avoided analyzing the actual collapse dynamics, violating everything that is known about physics and the performance of steel skyscrapers, unless the use of explosives is allowed for consideration (Chandler, 2010; Cole, 2023; MacQueen and Szamboti, 2009; Ryan 2013b).

In producing its report on the Twin Towers, NIST ignored or manipulated the physical testing done in support of the investigation, apparently because that testing did not support NIST’s pre-determined conclusion that the buildings failed due to fire. Later, when producing a report on WTC Building 7, NIST chose to not perform any physical testing. NIST’s report on WTC 7 ignored previous findings of sulfidation and intragranular melting of steel samples taken from the building debris. The report also contradicted facts about the building’s fire resistance plan and facts about the building’s structural features including the presence of shear studs that would invalidate NIST’s collapse hypothesis (Brookman, 2012; Ryan 2011a).

Ultimately, NIST’s final hypotheses for both the Twin Towers and WTC 7 were based on computer simulations that are not available to the public. NIST’s refusal to release that computer model data, which prevents the falsification of NIST’s findings and therefore negates the scientific basis for NIST’s reports, was justified by the absurd statement that releasing such data ‘might jeopardize public safety’ (Brookman 2012).

Set against the clearly fraudulent official scientific investigations, there is now an abundance of evidence providing confirmation of controlled demolition. This includes evidence of the active thermitic material in dust samples that was likely used to destroy the building structures (Harrit et al, 2009), the four-year study into WTC 7 at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (Hulsey, Quan and Xiao, 2020) which demonstrated that the symmetrical and initially free-fall collapse of WTC 7 could only have occurred if all of its 82 supporting columns were removed nearly simultaneously, and a wealth of other analyses refuting the official explanation (Szuladziński, Szamboti and Johns, 2013; Chandler, Walter and Szamboti, 2023; Cole, 2023; Jones, Korol, Szamboti and Walter, 2016; Korsgaard, 2024; MacQueen and Szamboti, 2009; MacQueen, 2006). The most likely remaining explanation involves pre-planned and deliberate destruction of the three buildings in New York on 11 September 2001 (Jones, Korol, Szamboti and Walter, 2016)

The overall official investigation into the 9/11 event, The 9/11 Commission, was also flawed. Its executive director was Philip Zelikow who, as noted earlier, co-authored the paper on purported terror threats prior to 9/11. Because Zelikow served on President G.W. Bush’s transition team and the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB), the 9/11 Commission cannot plausibly be described as independent of the US government. Zelikow created an outline for the 9/11 Commission Report before the investigation started and kept the outline secret from the Commissioners and staff. The final 9/11 Commission Report followed the pre-investigation outline closely (History Commons, 2009). Despite claiming to have done ‘exacting research’ to produce the ‘fullest possible account’, the 9/11 Commission Report states dozens of times that no evidence could be found for critical questions related to the investigation. This statement was untrue as evidence was available related to the topics cited by the Commission including Saudi funding for the alleged hijackers, the flying of Saudi nationals out of the country during the closure of US national airspace, insider trading related to 9/11, and statements from the US Environmental Protection Agency about the safety of air at Ground Zero (Ryan, 2011b). Overall, the Commission Report has been shown by Griffin (2004) to contain substantive ‘omissions and distortions’ whilst many of the questions raised by relatives of the victims remain unanswered (McGinnis, 2021).

C3) Media bias and propaganda

Much mainstream academic work supports claims that US media were highly compliant and deferential toward official propaganda narratives regarding 9/11 (e.g., Domke, 2004; Kellner, 2004) and this performance is consistent with well-established models of media-state dynamics (Herman and Chomsky, 1988; Hallin, 1986; Robinson et al, 2010). Writing in the Journal of 9/11 Studies, Gygax and Snow (2013) describe how the events of 9/11 were used to:

… justify an institutional revolution meant to complete a process of integration and coordination of all the assets of US national power through a strategic communication (SC) campaign deployed on a global scale. The “Global War on Terror” (GWOT) nurtured a narrative of crisis associated with this unprecedented public education effort. In order to sell its approaches, the United States government relied on a network of “experts”: military veterans, high-ranking officers such as Admirals as well as professional journalists and academics who contributed to forging a consensus, or, as Michel Foucault would call it, a “regime of truth” that claims a certain interpretation to be right and true, while ignoring or discrediting critics and dissenting narratives.

Generally, politicians and mainstream media have used the terms ‘9/11’ and ‘September 11th’ millions of times since the crimes of 9/11 were committed. They have invoked these terms as emotional drivers to use the attacks as justification for implementing policies that the US public would otherwise never have accepted. Moreover, the narratives created by use of these terms enabled a psychological operation that drove the dramatically increased militarization of US national discourse, military funding, and the new policy of ‘pre-emptive war’ (Altheide, 2009; Domke, 2004; Kellner, 2004).

Focused analysis has provided insights to media-state dynamics during the events of 9/11. Although many people believe that the Twin Towers collapsed as a result of the airplane impacts and the resulting fires, this is actually a revisionist theory. Those who witnessed the event first-hand were more likely to believe that the Twin Towers had been brought down by explosions such as is done with the demolition of buildings. In fact, destruction of the buildings by explosions was the predominant hypothesis among reporters covering the events (Walter and MacQueen, 2020). This perception was then supplanted by a propaganda campaign promoting the official explanation for the collapses and which was implemented by news anchors and commentators in the following hours and days after the events (MacQueen and Walter, 2022).

Following the immediate aftermath, media coverage of the 9/11 crimes continued to become increasingly subservient to official accounts. For example, reporting by The New York Times ignored many of the most relevant facts, promoted ever-changing and false official accounts, and belittled those who questioned the 9/11 events (Ryan, 2015). Well-established techniques involving smearing or character assassination (Attkisson, 2017; Samoilenko, 2019), coupled with the use of the ‘conspiracy theory’ label in order to discredit, are readily observable across media coverage of dissenting voices (de Haven-Smith, 2013; Ellefritz, 2022). Alternative media and political commentators were not immune to this propaganda-like coverage of the 9/11 crimes. In fact, ‘left-leaning’ alternative media were prone to support the official accounts and justified not looking closely at the facts by claiming fear of being discredited or fear of being distracted from more serious issues (Griffin, 2010). Before the end of the decade academic Cass Sunstein, appointed as head of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs in 2009, was advocating the use of cognitive infiltration techniques, whereby epistemic communities are infiltrated by individuals seeking to shore up official narratives in order to counter ‘conspiracy theories’ including those related to 9/11 (Sunstein and Vermeule, 2009). These covert techniques mirrored longstanding tactics known to be employed by state intelligence services (Glick and Smith, 1989).

Although the production of hard evidence for the explosive demolition hypothesis by independent scientists, as described above, did lead to some reasonably objective coverage by corporate, public, and independent media outlets (Woodworth, 2010), encouraging serious and objective engagement with analyses questioning the official narrative remained difficult and continues to be so today.

C4) Foreknowledge and planning

Just after September, a dozen national governments began investigations into possible insider trading (also known as informed trading) whereby put options were placed on United Airlines and American Airlines stocks (put options are essentially bets on the stock price going down). Also, the stocks of financial and reinsurance companies, as well as other financial vehicles, were identified as being associated with suspicious trades. Large credit card transactions, completed just before the attacks, were also involved. The US Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) named a number of people and companies that were suspected of being involved in the insider/informed trades. Furthermore, several studies by economists have substantiated the claim that there was financial activity consistent with foreknowledge of 9/11 (Potesham, 2006; Chesney, Crameri, and Mancini, 2014; Wong, Thompson, and Teh, 2011). Although the SEC investigators were clearly concerned about insider trading, and considerable evidence did exist, none of the investigations resulted in a single indictment. That’s because the people identified as having been involved in the suspicious trades were seen as unlikely to have been associated with al-Qaeda. Absurdly, the 9/11 Commission Report dismissed the significance of such activity, in one case asserting that 95 percent of the United Airlines September 6 trades came from ‘a single U.S.-based institutional investor with no conceivable ties to al Qaeda’ (9/11 Commission Report: p. 499; Note 130).

However, the suspects named by the SEC investigators were at least circumstantially connected to al-Qaeda in several cases and the amount of such evidence was considerable. Yet the quality of the FBI investigations, in which the suspects were not even interviewed, indicated that the Bureau and the 9/11 Commission were not interested in determining the truth behind these transactions (Ryan, 2010). Failure to investigate notwithstanding, the established fact of insider trading is evidence that contradicts the official 9/11 narrative which maintains that a surprise attack by a non-state terrorist group had been carried out.

Other less direct evidence of foreknowledge and planning involves the status of US air defences and military exercises. On September 11, 2001, Ralph Eberhart was Commander in Chief of the North American Aerospace Defense (NORAD), as well as commander of the US Space Command. In these roles, Eberhart was responsible for setting levels for the Infocon alert system that defends against attacks on communications networks within the Department of Defense. Just 12 hours before the 9/11 attacks, Eberhart oversaw the setting of Infocon to its least protective level. The setting of Infocon at the lowest level made the DOD computer networks, including the air defense system, susceptible to compromise including hacking. Eberhart was the sponsor of several, highly coincidental, military exercises that were going on that morning. The many military exercises that coincided with the attacks, including Vigilant Guardian, confused and disrupted the military’s ability to respond to the hijackings (Ryan, 2013).

Apart from multiple military exercises coinciding with the attacks, a significant number of the facilities and organizations impacted by the 9/11 attacks were engaging in training exercises on September 11th, later claimed to be merely coincidental. These included training exercises on the morning of 9/11 at the White House Situation Room, the New York City Emergency Operations Center, the World Trade Center computer network, Army bases near the Pentagon and New York City, the Washington DC police and fire departments, the National Reconnaissance Office, and the Joint Special Operations Command (History Commons).

To summarise the analysis so far, SDE indicators in the case of 9/11 include the preexisting ‘regime change’ policy, which was executed as soon as the event had occurred, and the involvement of deep actors who played key roles in enabling it. Regarding the event itself, authorities reacted immediately in terms of declaring attribution of responsibility to al-Qaeda and determining the policy response. Subsequent official investigations were manipulated in order to support official claims whilst propaganda was deployed across mainstream media in order to both promote the official narrative and suppress any dissent. Finally, foreknowledge of the event is evidenced by the existence of insider/informed trading as well as multiple ‘coincidental’ training exercises on the day.

Section Four: Examining the COVID-19 event for evidence of structural deep event indicators

SARS-CoV-2 was presented as a novel and extremely dangerous pathogen in early 2020 and, by March 2020, a global pandemic had been declared. In the context of what was widely interpreted as a major and potentially catastrophic health emergency, the ensuing responses around the globe involved unprecedented non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) including lockdowns, social distancing and masking (Ferguson et al, 2020) and, ultimately, the aggressive promotion of an experimental gene therapy ‘vaccination’ which, in many cases, was forced on people. As is now increasingly well documented, these interventions had deleterious consequences for the general health of a large part of the global population (Collateral Global, 2024).

A) Evidence of structural-level agendas

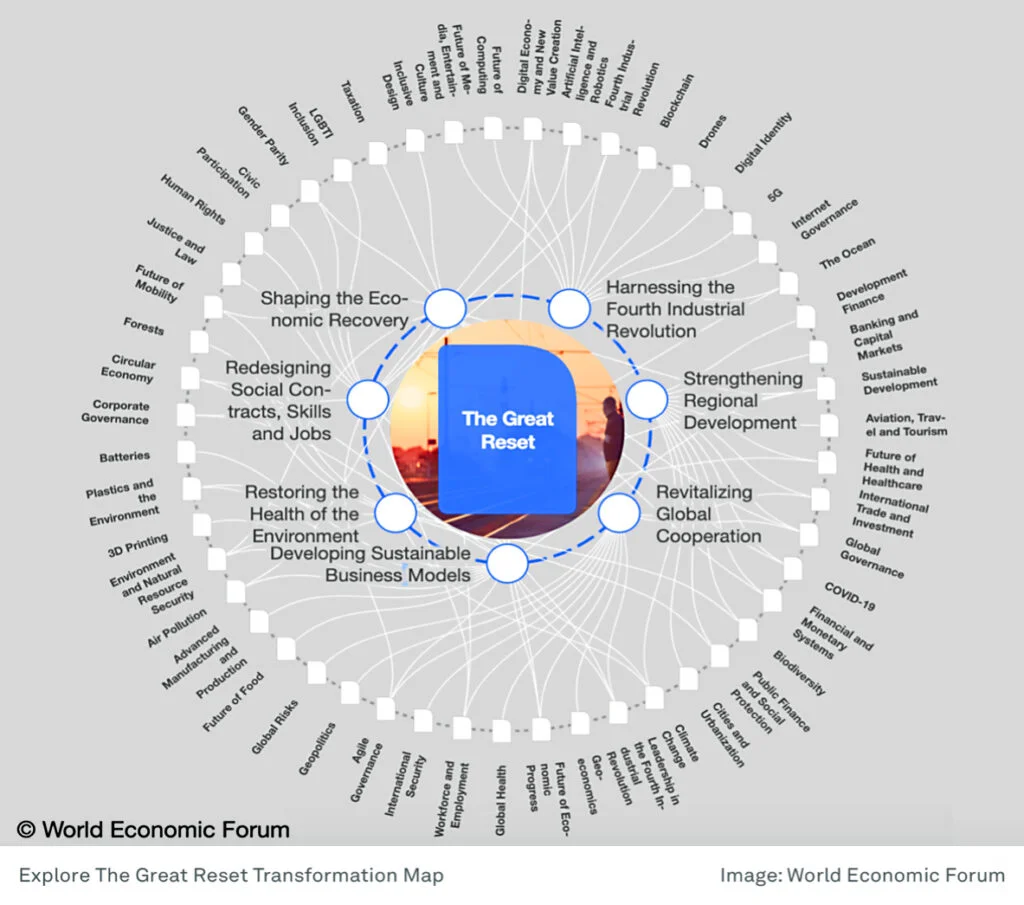

There are a number of structural-level agendas correlating with COVID-19 and which provide plausible explanations as to why powerful actors might have sought to manipulate events, either through instigation or exploitation. Most prominently, the ‘pandemic’ was presented as an opportunity to advance policies related to ‘stakeholder capitalism’ and the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) via the so-called ‘Great Reset’. The head of the influential World Economic Forum (WEF) think tank, Klaus Schwab, led the campaign to encourage ‘reset’ of ‘economic and social foundations’ and implementation of ‘stakeholder capitalism’. During the spring of 2020, he declared that ‘the COVID-19 crisis has shown us our old systems are not fit anymore for the 21st century. Noting that the ‘[t]he Pandemic represents a rare but narrow window of opportunity to reflect, reimagine, and reset our world’ (Schwab, 2020), he stated that we need a ‘Great Reset’ and, on the 9th of July 2020, published ‘COVID-19: The Great Reset’ (Schwab and Malleret, 2020). As can be seen in Image 1 below, the WEF’s vision was detailed and expansive.

Image 1 from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/now-is-the-time-for-a-great-reset/

A second significant process occurring in parallel with COVID-19 concerns the impending economic meltdown during the Autumn of 2019 and a series of policies designed to avert an incipient crisis in the financial markets which had remained in a problematic state since the 2008 subprime mortgage banking crisis (Schreyer, 2021; Titus, 2020; Titus et al, 2021; Vighi, 2021). In June 2019, the Swiss-based Bank of International Settlements Annual Economic Report (BIS, 2019) warned of impending crisis and, in August 2019, Blackrock Inc issued its white paper titled ‘Dealing with the next downturn’ (BlackRock, 2019). Vighi (2021) explains that:

Essentially, the paper instructs the US Federal Reserve to inject liquidity directly into the financial system to prevent “a dramatic downturn.” Again, the message is unequivocal: “An unprecedented response is needed when monetary policy is exhausted and fiscal policy alone is not enough. That response will likely involve ‘going direct’”: “finding ways to get central bank money directly in the hands of public and private sector spenders” while avoiding “hyperinflation. Examples include the Weimar Republic in the 1920s as well as Argentina and Zimbabwe more recently.”

In late August 2019, G7 central bankers met in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and James Bullard, President of the St Louis Federal Reserve, declared ‘[w]e just have to stop thinking that next year things are going to be normal’ (Financial Times, 2019). As the crisis in the repurchase agreements market (repo market) emerged in September, the US Federal Reserve began ‘pumping hundreds of billions of dollars per week into Wall Street, effectively executing BlackRock’s ‘going direct’ plan’ (Vighi, 2021). This plan shifted from ‘mid gear to high gear’ in March 2020, when COVID-19 provided the Federal Bank ‘with a huge cover story, the perfect distraction’ (Titus, 2020) as it ‘created 3$ trillion of new money in private hands’ (Titus, 2020). As Vighi (2021) explains, the lockdowns also helped avert the catastrophic hyperinflation that might have occurred with the implementation of the ‘Going Direct’ plan.

Third, Paul Schreyer (2021) documents the emergence of a biosecurity industrial complex premised on the alleged catastrophic threat posed by viruses, whether manmade or naturally occurring. For example, the Working Group on Influenza Pandemic Preparedness and Emergency Response (GRIPPE) was launched in 1993 and was followed by the John Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefence Strategies in 1998. The 2001 anthrax attacks, initially linked by authorities to al-Qaeda but actually emanating from a US military laboratory (MacQueen, 2014), provided the impetus for the acceleration of the biosecurity industrial complex whilst the John Hopkins Center rebranded as the Center for Health Security. As will be noted shortly, the John Hopkins Center played a critical role with respect to the COVID-19 event. Over the last 20 years a series of pathogenic events occurred, including SARS-CoV-1 (2002), Bird Flu (2005), Swine Flu (2009), Zika (2015), and culminating with SARS-CoV-2. These events have also been paralleled by simulation exercises. Specifically, the ‘Dark Winter’ exercise, hosted by the John Hopkins Center,5 gamed a terrorist release of smallpox virus just months before the anthrax attacks occurred in 2001 (MacQueen, 2014); The ‘Atlantic Storm’ exercise, convened by the Center for Biosecurity of UPMC, the Center for Transatlantic Relations of Johns Hopkins University, and the Transatlantic Biosecurity Network:

portrayed a summit meeting of presidents, prime ministers, and other international leaders from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean in which they responded to a campaign of bioterrorist attacks in several countries. The summit principals, who were all current or former senior government leaders, were challenged to address issues such as attaining situational awareness in the wake of a bio attack, coping with scarcity of critical medical resources such as vaccine, deciding how to manage the movement of people across borders, and communicating with their publics. Atlantic Storm illustrated that much might be done in advance to minimize the illness and death, as well as the social, economic, and political disruption, that could be caused by an international epidemic, be it natural or the result of a bioterrorist attack. (Smith et al, 2005)

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s latest book puts forward the case that SARS-CoV-2 was likely the consequence of bioweapons research orchestrated by US and Chinese authorities and corporate actors (Kennedy, 2023).

A number of researchers associate the biosecurity industrial complex with a political drive to, broadly speaking, strengthen control over populations, serve the interests of powerful corporations such as the pharmaceutical industry (Big Pharma), and advance various technocratic agendas including transhumanism (Bell, 2023; Chossudovsky, 2021; Davies, 2022; Elmer, 2022; Hughes, 2024; Kennedy, 2022; Kheriaty, 2022, van der Pijl, 2022; Robinson, 2023(22); Thiessen, 2023). At the time of writing, the push to implement a global level biosecurity regime via the WHO pandemic preparedness agenda/treaty is underway.

B) Evidence for the involvement of Deep Actors (State and Non-State)

Just when Covid was being introduced as a threat to the public, intelligence and military agencies began to take a leading role in communications about the crisis. In the US, the White House ordered federal health officials to treat coronavirus meetings as classified, which was an unusual action to take. The National Security Council was behind this classification and increased secrecy which included communications about infection rates, recommendations for the public, and other topics (Rosten and Taylor, 2020). Kennedy refers extensively to the CIA throughout his work The Real Anthony Fauci and notes, for example, that a Senior Fellow and cofounder of the aforementioned John Hopkins Center was a ‘CIA spook and pharmaceutical industry lobbyist named Tara O’Toole’ (2022). Kennedy (2022: p. 839) also points out that:

(v)irtually all of the scenario planning for pandemics employs technical assumptions and strategies familiar to anyone who has read the CIA’s notorious psychological warfare manuals for shattering indigenous societies, obliterating traditional economies and social bonds, for using imposed isolation and the demolition of traditional economies to crush resistance, to foster chaos, demoralization, dependence and fear, and for imposing centralized and autocratic governance.

In the UK, management of Covid messaging and responses included the involvement of intelligence and military actors. This included putting the person expected to be the next chief of MI6 (Secret Intelligence Service [SIS]) in charge of a ‘bioterrorism centre’ in order to evaluate the threat and implement intervention. Additionally, the UK intelligence agency known as Government Communication Headquarters (GCHQ) was granted powers over the NHS’s computer systems (Ryan, 2020). In the UK, military involvement also came via the 77th Brigade, a unit tasked with information warfare. In an answer to a written question in parliament,6 it was confirmed that ‘members of the Army’s 77th Brigade are currently supporting the UK government’s Rapid Response Unit in the Cabinet Office and are working to counter dis-information about COVID-19’ (Robinson, 2020; UK Column, 2020). In Germany, authorities had already created a Department for Health Security in late 2019, and which was headed by a General, Hans Ulrich Holtherm, from the Bundeswehr (Germany Army) (Schreyer, 2020: p. 36).

International organisations and associated power elite networks were also linked to the COVID-19 event including, and most notably, the WHO, the WEF (see discussions above and below) and financial actors such as BlackRock and the Federal Reserve. Although not commonly understood as ‘deep state’ actors, these organisations are not accountable to populations in the way that democratic governments, at least in theory, are supposed to be. This is most obvious in the case of the financial actors who operate, to a very large extent, outside of the public gaze. But it also applies to organisations such as the WHO, which is a UN-linked organisation heavily funded by private actors such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Broadly, the role and influence of these actors highlights the extent to which significant political and economic power relevant to COVID-19 was located above and beyond the traditional nation state (Woodworth, Witt and Cobb, 2023).

In addition, although the origins of SARS-CoV-2 remain controversial, as is the question of whether or not there was a significant new pathogen, it is the case that a laboratory in Wuhan, the city in which the virus is purported to have first emerged, was connected to a number of deep actors. Specifically, Anthony Fauci’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) ‘oversaw a large program on biodefence and research’ which included Peter Daszak of EcoHealth Alliance (Thacker, 2023). In turn, research on coronaviruses was conducted in partnership with the Wuhan Institute (Chan, 2024). Precisely what this might mean in terms of understanding events will be returned to later. Also, and with respect to the development of ‘covid countermeasures’, Latypova (2022) presents evidence indicating that Covid countermeasures, including ‘development of vaccines and treatments’, were set not by public health agencies but rather by the National Security Council.

C) Evidence of event exploitation, instigation and deception

C1) Rapid actions in response with minimal investigation of initial events

As noted above, SARS-CoV-2 was presented by authorities as a novel and exceptionally dangerous pathogen, rapidly spreading and threatening to cause widespread severe illness and death. The existence of a new virus was first publicly announced on the 31st of December 2019 when the World Health Organisation (WHO) China office advised of a ‘pneumonia of unknown etiology’ (WHO, 2020a). At that stage 44 patients were being treated in hospital and nobody was reported to have died. By the 9th of January 2020, Chinese authorities had made a ‘preliminary determination’ of a new coronavirus. On the day the first actual death was reported, the 11th of January, the WHO (2020b) declared it had received the genetic sequences from China for a novel coronavirus. By the end of January, the WHO Emergency Committee had declared a ‘Public Health Emergency of International Concern’ (PHEIC) and, on the 11th of March, COVID-19 was declared a pandemic (Cucinotta and Vanelli; 2020). As Schreyer (2021: pp. 146-147) notes, the WHO declaration, claiming to ring ‘the alarm bell loud and clear’ (WHO 2020c), came at a point when only 4,000 deaths had been reported worldwide and when figures for China and Korea were rapidly decreasing.

With respect to the origins of SARS-CoV-2, some have argued that it was a consequence of a lab leak, possibly resulting from research supported by EcoHealth Alliance/Fauci-linked scientists at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (e.g., Chan, 2024; Chan and Ridley, 2021; Kennedy, 2023; Thacker, 2023). On the other hand, others have questioned the claim of there being a novel and exceptionally dangerous pathogen in circulation. In the German context, Professor Stefan Homburg provided analysis of official data and stated in late 2023, during a talk in the Bundestag (German parliament), that ‘respiratory diseases were inconspicuous in 2020 and 2021’ and that the ‘age-adjusted mortality rate was between the values of 2018 and 2019’ (Homburg, 2023). Analysis of worldwide mortality data by Verduyn, Engler and Kenyon (2023a&b) indicates that ‘Covid deaths should be categorized as part of the baseline of normal deaths, rather than as the driving force behind excess deaths’. Rancourt et al (2022) analyzed US all-cause mortality to show that its behaviour was inconsistent with ‘pandemic behaviour caused by a new respiratory virus’ (see also Rancourt, 2020; Rancourt, Hickey and Linard, 2024).

Furthermore, focused examination of two alleged mass casualty events, one in New York and one in Lombardy (Italy), both of which were critical in terms of cementing the impression of a deadly new virus, show that the data is inconsistent with a rapidly spreading and particularly deadly virus (Engler, 2023; Verduyn, Hockett, Engler, Kenyon and Neil, 2023). Their research, in fact, questions the accuracy of official figures whilst, furthermore, Hockett (2024) demonstrates that evidence of death toll in New York has yet to be provided by authorities. Meanwhile, evidence of SARS-CoV-2 circulation prior to the events of late 2019/early 2020 indicate that there had been no sudden outbreak and spread of a novel pathogen at the time authorities claimed there to have been (Apolone et al, 2021; Basavaraju et al 2020; Bonguili, 2022; Fongaro et al, 2021).

One possibility here is that the illusion of a new and unusually deadly spreading virus was created, as discussed below in C2, via fraudulent testing protocols and misattribution of iatrogenic harms to SARS-CoV-2 (Fenton and Neil, 2024: p. 353; PANDA, 2024). Another is that an unexceptional pathogen was in circulation and was then presented as far more deadly than it actually was.

The implications of this question for the Wuhan lab leak hypothesis mentioned above remain to be fully understood. Some have argued that the Wuhan lab leak claim might be serving as a distraction whereby a narrative built around a dangerous virus leaking from a lab disguises the fact that there was actually no particularly dangerous pathogen in circulation (see Engler, 2024). It might also be the case that a pathogen was adulterated or engineered, possibly with the involvement of the previously mentioned deep actors, but was not nearly as virulent as claimed by authorities and assumed by some advocates of the Wuhan leak hypothesis. Greater clarity on the nature and origins of SARS-CoV-2 is necessary before firm conclusions can be reached regarding the Wuhan lab leak hypothesis.

In sum, regardless of the nature and origins of SARS-CoV-2, there appears, as Chossudovsky (2022: p. 17) argues, to have been no scientific basis for the rapid launch of a worldwide public health emergency and the accompanying unprecedented interventions. Documents recently obtained through freedom of information requests in Germany provide further evidence that the German ‘pandemic’ response was driven by political, not scientific, considerations (Schreyer, 2024).

C2) Manipulation of science

At least three steps enabled construction in the public mind that there existed a major and deadly pandemic warranting unprecedented interventions and societal disruption.

First, the definition of a pandemic was, in 2009, altered so as to exclude ‘severity’ as a defining feature. Immediately prior to the swine flu outbreak the WHO’s definition was altered through the removal of the requirement that, for a pandemic to be declared, there needed to be ‘simultaneous epidemics worldwide with enormous numbers of deaths and illnesses’ (Fumento, 2009). Up until this point the commonly understood meaning of ‘pandemic’ was that it was akin to, for example, the historic post WW1 ‘Spanish’ flu pandemic which is commonly reported to have caused 50 million deaths. After 2009, any pathogen with sufficient geographic spread could be labelled a pandemic.

Second, an inappropriate use of the PCR test was used in order to identify COVID-19 cases. The in(famous) Drosten paper of 2020 (Corman et al, 2020) provided the initial scientific basis for this test and was published only three weeks after the WHO had announced the discovery of the new respiratory virus. It is important to note, however, that the test Drosten’s team developed was not what would be broadly used to test for SARS-CoV-2 in the general population. In fact, of the seven testing protocols developed by various nations only the test used in Germany by Charité – University of Medicine Berlin reflected the same genetic targets as the Drosten test (WHO, 2020d).

The most widely used PCR test for identification of SARS-CoV-2 was the US CDC test kit, reported by the CDC to have been distributed to all US states and 30 other countries including 191 international labs. The CDC test kit targeted only one gene of SARS-CoV-2, the N gene. Because the N gene (for nucleocapsid) is highly conserved across coronaviruses, the CDC kit did not identify a unique coronavirus. This problem was exacerbated just after CDC had shipped its kit as state laboratories began to report false positives when using the kit. CDC identified one of its primers as the cause of the problem, stating that it was contaminated, and instructed all users to discard that one reagent and continue testing. At the same time (March 15, 2020), CDC instructed labs to forego any confirmatory testing. Obviously, the lack of confirmatory testing ensured that no false positive results would be identified but did nothing to prevent false positive results from being generated (Ryan, 2020).

PCR testing for viruses is well known to have issues affecting its accuracy and interpretation. PCR will detect viral fragments, remaining from previous infection, as well as intact virus, and does not distinguish between the two. That is an important reason why PCR testing cannot test for infection but only for the presence of short nucleotide sequences. Additionally, if the cycle threshold is set too high, as was the case when some laboratories emphasized sensitivity over specificity for SARS-CoV-2, false and/or clinically meaningless positives will result (Verduyn, 2023c).

Third, while some have questioned whether SARS-CoV-2 was a ‘novel’ virus as of January 2020 (Verduyn, 2023c), new policies for reporting the cause of death in 2020 were indeed novel. The WHO issued new guidance for recording cause of death in April 2020, stating that ‘COVID-19 should be recorded on the medical certificate of cause of death for ALL decedents where the disease caused, or is assumed to have caused, or contributed to death’ (WHO 2020e). That is, test results indicating presence of SARS-CoV-2 were not required to establish COVID-19 as a contributing cause of death, only a doctor’s opinion that COVID-19 might have been involved.7

Similarly, the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) established unique rules for recording cause of death that also did not require a test result indicating the presence of SARS-CoV-2. Merely suspecting that COVID-19 might have been a factor was enough ‘to report COVID-19 on a death certificate as “probable” or “presumed”’ (DHHS 2020). This new guidance was reinforced by the fact that, as CDC director Robert Redfield stated in remarks to the US Congress, there was also a monetary incentive for hospitals to report deaths as COVID-19 (CSPAN, 2020). Dr. Redfield was questioned by a Congressman about ‘perverse incentives’ that had caused hospitals and doctors to claim someone had died of Covid when other comorbidities were more impactful. In response, Redfield said ‘I think you’re correct’ that hospitals preferred to list Covid on the death certificate ‘because there is greater reimbursement’.

Overall, the false positive testing, the new presumptive policies on reporting cause of death, and the incentives to report deaths as COVID-19, led to exaggerated reporting of COVID-19 cases and deaths.

C3) Media Bias and Propaganda

During COVID-19 propaganda has been deployed across democracies on an unprecedented scale (Robinson 2024, 2022). In order to gain compliance with the unorthodox and intrusive measures adopted during the COVID-19 event, many forms of ‘non-consensual persuasion’ (Bakir et al, 2019) were used, ranging from manipulated messaging designed to increase ‘fear levels’ through to coercion. Early on it came to light that behavioural scientists were providing advice to the UK government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE). UK Column reported that this group, named the ‘Scientific Pandemic Influenza group on Behaviour (SPI-B)’, was (re)convened on 13 February 2020 (UK Column, 2020). One document produced by this group identified ‘options for increasing adherence to social distancing measures’ which include ‘persuasion’, ‘incentivization’ and ‘coercion’. In the section on ‘persuasion’ it states that the ‘perceived level of personal threat needs to be increased among those who are complacent, using hard-hitting emotional messaging’. The document also referred to using ‘media to increase sense of personal threat’ (Dodsworth, 2022: Dodsworth et al, 2021; Sidley, 2024).8 These approaches were mirrored at the global level. In February 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) established the Technical Advisory Group on Behavioural Insights and Sciences for Health (TAG): ‘The group is chaired by Prof. Cass Sunstein and its members include behavioural change experts from the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Professor Susan Michie, from the UK, is also a TAG participant’ (Davis, 2022).

Propaganda involves not only active promotion of specific narratives, it also involves the creation of silences. Here, the COVID-19 event is replete with examples of censorship (Robinson, 2024, 2022). In 2023, the US Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit came to a decision regarding media censorship during the Covid crisis. In the case of Missouri v. Biden, the court’s decision detailed a campaign of pressure undertaken by some US officials to purge ideas from the internet that challenged the government’s position on Covid.9 The decision described communications between social media companies and officials from the White House, the CDC, the FBI, and other government agencies that violated the First Amendment. Starting in 2020, these federal officials were in contact with social media companies about the spread of Covid-related ‘misinformation’ on their platforms. The companies were also threatened by officials and ordered to take down posts and close accounts related to dissenters who spoke out about the ‘COVID-19 lab leak theory, pandemic lockdowns, and vaccine side-effects’, among other things (Atkinson, 2023).