Dr. Atif Kubursi is a professor emeritus of economics at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada. In 1982, he joined the United Nations Industrial Organization as Senior Development Officer. In 2006, he was appointed Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (UN-ESCWA). He has published extensively in the areas of macroeconomics, economic development strategies, international trade, impact analysis, and regional planning.

For over three months now the Israeli army has repeatedly attacked Palestinian civilian communities in both Gaza and the West Bank. Indeed, the U.N. has warned the international community about “a genocide” in the making.1 The Palestinian death toll has likely reached over 20,000 with about 50,000 wounded and where 70% of the casualties are women and children. Many thousands more are feared lost in the rubble or beyond the reach of ambulances. As of now, over 60% of the housing infrastructure has been so far destroyed and so are scores of hospitals, schools, mosques, churches, cultural sites, businesses and UN offices. The bloodletting and destruction perpetrated by the IDF is mounting as the US has blocked even a UNSCR vote for a cease fire, and Israel is refusing to heed the UN General Assembly call for a cease fire where 153 countries have voted for the resolution and only 10 countries voted against it on December 11, 2023.

Though Israel and her supporters have framed the offense as a war against Hamas, many knowledgeable observers throughout the Middle East and beyond don’t accept this characterization. They believe other interests are behind the violence. A few other factors are believed to be at play here including oil and gas, particularly those in the eastern Mediterranean, the Ben Gurion’s Canal and the new trade route connecting India to Europe through Israel that the US is hoping to replace the Chinese Silk Road. These critical economic mega projects appear to be equally likely fundamental reasons behind this carnage. They are by no means the only objectives of the Israelis, but they constitute a credible set of reasons that explain the targeting the emptying of Gaza.

John Mearsheimer on December 12, 2013 has documented that the objective of the Israeli invasion of Gaza is to make it uninhabitable. He noted that the New York Times has reports that “it is part of normal Israeli discourse to call for Gaza to be “flattened,” “erased,” or “destroyed.””2 He even quoted one retired IDF general to have proclaimed that “Gaza will become a place where no human being can exist,”3 Going even further, a minister in the Israeli government suggested dropping a nuclear weapon on Gaza.4 These statements are not being made by isolated extremists, but by senior members of Israel’s government.

One wonders how would killing children and women increase the security of Israel and protect Israelis against future violent episodes. Why would starving Gazans and transferring large populations from one place into another ever build a better peaceful future for the Israelis? Why has Israel sought driving Gazans into Sinai? It is increasingly becoming apparent that pushing Gazans into Sinai and making Gaza unlivable are key Israeli objectives. But the real question is why will driving 2.2 million Gazans away from Gaza bring peace and security for Israel? If this is not the real objective from this transfer, then what are the real objectives of Israel’s ethnic cleansing campaign in Gaza?

Critics have raised questions about the real objectives of the campaign right from its outset and have deemed that the scale of destruction and murder of civilians to be inconsistent with the declared objectives; there is a nagging concern here that there are other undeclared objectives and future plans for Gaza.5 Surely establishing Israel as a pure Jewish state free from any other group has always been a critical objective of the Zionists. But this does not mean that there are no other objectives driving this violent campaign.

In what follows a few possible objectives and explanations are flagged out as alternative driving forces that could explain better why and what is happening in Gaza. There are a few serious economic projects on the drawing board and some actual new lucrative economic returns being currently reaped from the new discoveries of oil and gas and the new envisaged trade routes that are potentially driving the genocide and the objective of driving Gazans from where they are now.

These objectives are not necessarily mutually exclusive of other declared military and political objectives such as destroying Hamas, eliminating its military and political leadership, ethnically cleansing Palestinians to create a pure Jewish state and grabbing more Palestinian land. The argument here is simple and direct; the economic returns of the “mega projects” that depend on emptying and controlling Gaza are certainly credible and perhaps as substantive as the declared objectives, if not more credible.

The Levant Basin

Among the most important new recent economic developments is the great discovery of large deposits of gas and oil in the Eastern Mediterranean. These deposits have gained notoriety and value as Russian gas and oil supplies became less available and accessible by Europe, particularly after Nord-Stream II was blown out last year as the Ukraine-Russian war raged in intensity.

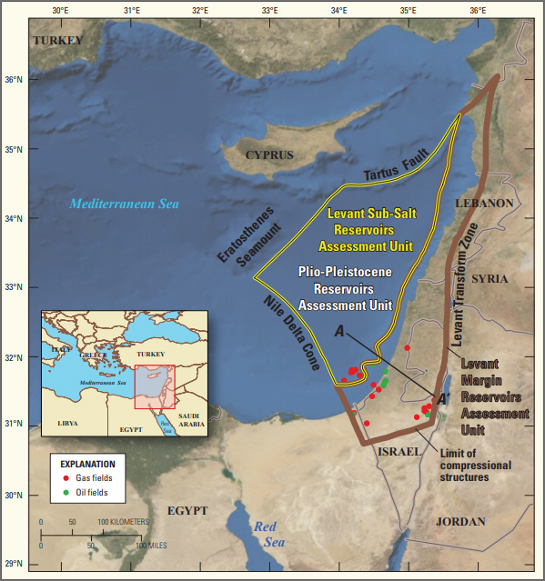

Map 1. Location of the three assessment units in the Levant Basin Province

in the Eastern Mediterranean

Source: USGS https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2010/3014/pdf/FS10-3014.pdf. This map is not an official United Nations map, it is shown only for illustration purpose.

The Levant Basin Province encompasses approximately 83,000 square kilometers of the eastern Mediterranean area (see Map 1). The area is bounded to the east by the Levant Transform Zone bounded by Cyprus, to the north by the Tartus Fault in Syria, to the northwest by the Eratosthenes Seamount, to the west and southwest by the Nile Delta Cone Province boundary in Egypt, and to the south by the limit of compressional structures in the Sinai.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimated a mean (average) of 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil and a mean of 122 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas in the Levant Basin Province.6 This makes this basin as one of the most important gas resources in the world. These resources do not coincide with political borders. Several defining characteristics of oil and gas separate them from other natural resources. First, they do not obey political borders and can therefore straddle many national borders. Second, they take several thousand years to accumulate underground such that the current owners are either not necessarily the true or only owners. Third, both of these resources can be stored at zero cost for decades, centuries and even millennia. Typically, their optimum exploitation depends, in part, on current interest rates and the expected price increase. Fourth, they may be part of the global commons where efficiency and equity considerations require unitization and common exploitation, otherwise a vicious zero-sum game will emerge where one party is able to benefit at the expense of other parties. Fifth, both oil and gas are non-renewable resources, any exploitation of which reduces what is available for others or for future generations. This fact adds vertical, intergenerational, equity constraints to the horizontal, intra-generational, equity issues. Sixth, the gap between potential and realized values of oil and gas exploitation that is manifest in most “normal” and “stable” jurisdictions is further exacerbated in the OPT by the lack of clear demarcation of property rights. Seventh, gas is fugitive and can seep from reservoir into another which makes it difficult to contain in one place and to be exploited by one party.

The new discoveries of oil and gas in the Levant Basin to the tune of 122 trillion cubic ft. of gas at a net value of US$453 billion and 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil at a net value of about US$71 billion, offer an opportunity to distribute and share a total of US$524 billion among the different parties in addition to many intangible but substantive advantages of energy security and potential cooperation among old belligerents. It can also be, as is now the situation, a source of potential conflict if individual parties exploit these resources without due regard to the fair share of others.

With the escalation of energy prices triggered by the Ukraine-Russia war, the values of these deposits in the Levant basin have measurably increased. It is estimated that these deposits are now worth $2 trillion. Only Israel is currently exploiting these reserves.

The experience of the US in dealing with the shared oil fields in Texas and Oklahoma is relevant here. These fields were unitized in order to raise the collective profits that any independent and individual exploitation could diminish. The superiority of unitization stemmed as an implication of the “Coase Theorem” which suggested that collective profits and higher efficiency necessitate the separation of utilization of a common resource from property rights.7 These fields could be unitized and their development could be undertaken on behalf of all parties whose property rights would be ascertained prior to exploitation. The economic principle of efficiency dictates this unitization, but this cannot be assured unless the parties agree to a fair sharing formula and whose transaction and monitoring costs are limited and low. The Palestinians have a major stake not only in the fields under their land but in all the common reserves in this Basin for no other reason than the fact that these resources are common and do not obey political boundaries.8

Geologists and natural resources economists have confirmed that the Occupied Palestinian Territory lies above sizable reservoirs of oil and natural gas wealth, in Area C of the occupied West Bank and the Mediterranean coast off the Gaza Strip. However, occupation continues to prevent Palestinians from developing their energy fields so as to exploit and benefit from such assets. As such, the Palestinian people have been denied the benefits of using this natural resource to finance socioeconomic development and meet their need for energy. The accumulated losses are estimated in the billions of dollars. The longer Israel prevents Palestinians from exploiting their own oil and natural gas reserves, the greater the opportunity costs and the greater the total costs of the occupation borne by Palestinians become.

Gaza’s Gas Fields and Meged Oil Field in the West Bank9

In November 1999, the PNA signed a twenty-five year contract for gas exploration with the British Gas Group (BG). Earlier that year BG discovered a large gas field, which it named Gaza Marine, at a distance of 17 to 21 nautical miles from the Gaza coast. In 2000, BG drilled two wells in the field and carried out feasibility studies with good results.

The Oslo Accords, specifically the 1994 Gaza-Jericho Agreement, confirmed by the 1995 ‘‘Oslo II’’ interim agreement had given the PNA maritime jurisdiction over its waters up to 20 nautical miles (23 statute miles) from the coast.10 This Agreement (Oslo II) allows fishing, recreational, and presumably, other economic activities such as drilling. Plans for the development of the gas fields did not go unchallenged. It was met with Israeli resistance in both business and political circles. Companies in the Israeli Yam Thetis consortium, which was set up to operate in adjacent Israeli gas fields and made its first discovery in 1999, petitioned the Israeli government to forbid BG from drilling off Gaza; the reason given was that the PNA is not sovereign government and therefore cannot benefit from the Law of the Sea Treaty.11

Nevertheless, in July 2000 the then Israeli Prime Minister, Ehud Barak, granted BG security authorization to drill the first well, Marine-1, as part of a political (but not legally binding) recognition by Israel that the well was under PNA jurisdiction.12 BG began drilling the second well, Marine-2, in November 2000, in order to assess the gas’s quantity and quality.

On 27 September 2000, literally on the eve of the second intifada, the head of the PNA, President Arafat, accompanied by Palestinian (Lebanese) businessmen from Consolidated Contractors International Company (CCC) and the media, lit the flame proving the presence of gas at the BG offshore exploration platform.13 In a recoded speech Arafat declared that the gas was ‘‘a gift from God to us, to our people, to our children. This will provide a solid foundation for our economy, for establishing an independent state with holy Jerusalem as its capital.’’14 The president of BG asserted that the gas was of good quality and of sufficient quantity to satisfy Palestinian demand and provide for exports. The reserves were estimated at 1 trillion cubic feet (tcf).15 Barak’s authorization to drill the second well, and the successful gas strikes at both, seemed to promise a potential windfall for the Palestinian people, enhancing the viability of their economy as well as their quest for justice and sovereignty.

The contract signed in 1999 divided the ownership between the parties involved; giving BG 90 per cent of the license shares and the PNA 10 per cent until gas production would begin. Subsequently, the PNA’s share was slated to increase to 40 per cent, of which 30 per cent would have been held by the Consolidated Contractors Company developing the project. The PNA approved BG’s development plan, which included the construction of a pipeline linking the fields to Gaza at an estimated cost of $150 million, in July 2000.16

The PNA-BG-CCC agreement included field development and the construction of a gas pipeline.17 The BG licence covers the entire Gaza offshore marine area, which is contiguous to several Israeli offshore gas facilities (See Maps 1, 2 & 3). It should be noted that 60 per cent of the gas reserves along the Gaza-Israel coastline belong to Palestine.18

Negotiations between BG, the PNA, and the Israeli government were launched in summer 2000 within the Oslo narrative of economic cooperation. Israel needed gas, and the PNA could offer it, so a deal was seen as constituting a good fit between Israeli energy need and Palestinian supply. The New York Times noted in September 2000, ‘‘Palestinians and Israelis will both profit if they can work together in a high-stakes partnership. They need each other for the efficient development of these offshore reserves.’’19 This failed to mention that efficiency is necessary but not sufficient for cooperation. Far more important are the terms of cooperation and the respective shares in the distribution of rent from the realized efficiencies.

Thus in June 2000, BG proposed to supply gas from Egypt, Gaza, and Israel (the fields off Ashkelon) to the state-owned Israel Electric Corporation (IEC). At the same time, two other groups were also proposing long term supply contracts to Israel. One of these was Yam Thetis, a consortium of three Israeli companies and one U.S. firm (Samedan), which, as mentioned above, had opposed Israel’s granting drilling rights in Palestinian waters. The other was East Mediterranean Gas (EMG), a partnership between the Israeli firm, Merhav, the Egyptian National Oil Company, and an Egyptian businessman, which had been established to export Egyptian gas to Israel.20

The IEC refused to buy gas from Gaza, declaring that it was more expensive than Egyptian gas. Subsequent Israeli media reports told a different story arguing that the main reason for the refusal was political and was on account of the Israel’s newly elected (as of spring 2001) Prime Minister, Ariel Sharon, vetoing any purchase of Palestinian gas.21 Yet this veto was lifted at least partly in May 2002 at the urging of British Prime Minister, Tony Blair, who believed that such projects could help advance a peace process severely strained by the intifada.22

Sharon accepted to negotiate an agreement for the annual supply of 0.05 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of Palestinian gas for a period of ten to fifteen years.23 But in summer 2003 he reversed his position once again and refused to allow funds to flow to the PNA claiming that they could be used to support “terrorism”. This latter explanation is also open to question given that Israel had already announced that Palestinian gas revenues would be transferred to a special account—the same account, consolidated under the PNA finance minister. This is the same account that was being used for international aid and tax clearance revenues remitted by Israel.

Some political observers claimed that conditions were more favorable to the negotiations following the death of Arafat in November 2004. They based their claim on a presumed new climate that have emerged from a combination of developments that included the election of Mahmud Abbas as PNA president in January 2005; a PNA reform cycle satisfactory to the international community; and Ariel Sharon’s replacement by Ehud Olmert as Prime Minister of Israel in January 2006.

On 29 April 2007, the Israeli cabinet approved Olmert’s proposal to authorize renewed discussions with BG. In May, terms of a contract were officially revealed: Israel would purchase 0.05 tcf of Palestinian gas for $4 billion annually starting in 2009.24 Under this plan, gas would be piped to Ashkelon for liquefaction in Israel and thence to supply the Israeli market and cover Gaza’s limited needs. This, it was argued, would generate mutual benefits as well as mutual dependency deemed to ‘‘foster a good atmosphere for peace.’’25

But the political context once again changed. On 14 June 2007, under a new government; Gaza Strip split politically and administratively from the West Bank. The new government in Gaza declared that it would change the terms of the contract, particularly with regards to the Palestinian share (10 per cent). ‘‘If the contract is changed, the economic consequences on the Palestinian society would be tangible … The Palestinians would be depending on their resources rather than international aid,’’ it argued.26 Nonetheless, negotiations between Israel and the PNA, which controls the West Bank, continued for a time, bypassing the governing authority in Gaza.

In September 2007, the then Israeli chief of staff strongly advised the Israeli government not to conclude an agreement with BG: ‘‘Clearly, Israel needs additional gas sources, while the Palestinian people sorely need new sources of revenue. However, with Gaza currently a radical Islamic stronghold, and the West Bank in danger of becoming the next one, Israel’s funneling a billion dollars into local or international bank accounts on behalf of the Palestinian Authority would be tantamount to Israel’s bankrolling terror against itself.’’27

The Israeli military operation in the Gaza Strip in December 2008 had several implications related to the control and ownership of strategic offshore gas reserves. In the wake of the operation, Palestinian gas fields were effectively brought under Israeli control with no regard to international law. The issue of sovereignty over Gaza’s gas fields is crucial. From a legal standpoint, the gas reserves belong to Palestine.

Subsequent to the death of Yasser Arafat, the separation of the West Bank and Gaza and the three Israeli military operations in Gaza, Israel established de facto control over Gaza’s offshore gas reserves. The BG has been dealing with the Tel Aviv government.28 In turn, the de facto authority in Gaza has been bypassed in regards to exploration and development rights over the gas fields.

As mentioned above, in May 2007, the Israeli Cabinet approved a proposal by Prime Minister Ehud Olmert “to buy gas from the Palestinian Authority.” The proposed contract was for $4 billion, with profits in the order of $2 billion, of which one billion was to go the Palestinians. Tel Aviv, however, had different plans for sharing the revenues with Palestine. An Israeli team of negotiators was set up by the Israeli Cabinet to thrash out a deal with the BG Group, bypassing both the Hamas government and the PNA: “Israeli defense authorities want the Palestinians to be paid in goods and services and insist that no money go to the Hamas-controlled Government.” The effect was essentially to nullify the contract signed in 1999 between the BG and the Palestinian National Authority.29

Under the proposed 2007 agreement with BG, Palestinian gas from Gaza’s offshore wells was to be channeled by an undersea pipeline to the Israeli seaport of Ashkelon, thereby transferring control over the sale of the natural gas to Israel. The deal fell through. The negotiations were suspended: “Mossad Chief opposed the transaction on security grounds, that the proceeds would fund terror”.30

Israeli actions in effect foreclosed the possibility that royalties be paid to the Palestinians. In December 2007, the BG withdrew from the negotiations with Israel and in January 2008 it closed its office in Israel. Plans for the Israeli military strike in Gaza were set in motion six months, or more, before it was carried out in December 2008. According to Israeli military sources: “Sources in the defense establishment said Defense Minister Ehud Barak instructed the Israel Defense Forces to prepare for the operation over six months ago [June or before June], even as Israel was beginning to negotiate a ceasefire agreement with Hamas.31

That very same month (June 2008), the Israeli authorities contacted British Gas, with a view to resuming crucial negotiations pertaining to the purchase of Gaza’s natural gas: “Both Ministry of Finance director general Yarom Ariav and Ministry of National Infrastructures director general Hezi Kugler agreed to inform BG of Israel’s wish to renew the talks. The sources added that BG has not yet officially responded to Israel’s request, but that company executives would probably come to Israel in a few weeks to hold talks with government officials.”32

The decision to speed up negotiations with the BG coincided, chronologically, as argued by Michel Choussodvsky (2006) with the planning for the military strike on Gaza initiated in June. It would appear that Israel was anxious to reach an agreement with the BG prior to the strike, which was already in an advanced planning stage.33

Moreover, the Israeli government, with the knowledge that a military invasion was on the drawing board, conducted these negotiations with British Gas. Apparently, the Israeli government was also contemplating a new “post war” political-territorial arrangement for the Gaza strip. In fact, negotiations between British Gas and Israeli officials were ongoing in October 2008, 2-3 months prior to the commencement of the military strike on December 27th, 2008.

In November 2008, the Israeli Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of National Infrastructures instructed the IEC to enter into negotiations with British Gas on the purchase of natural gas from the BG’s offshore concession in Gaza.34 “Ministry of Finance director general Yarom Ariav and Ministry of National Infrastructures director general Hezi Kugler wrote to IEC CEO Amos Lasker recently, informing him of the government’s decision to allow negotiations to go forward, in line with the framework proposal it approved earlier this year. The IEC board, headed by Chairman Moti Friedman, approved the principles of the framework proposal a few weeks ago. The talks with BG will begin once the board approves the exemption from a tender.”35

A new territorial arrangement emerged subsequent to the Israeli military operation in Gaza in December, 2008, including the militarization of the entire Gaza coastline and the confiscation of Palestinian gas fields under Israeli sovereignty over Gaza’s maritime areas. As such, the Gaza gas fields have been de facto integrated into Israel’s offshore installations in contravention of International Law, which are contiguous to those of the Gaza Strip. (See Maps 2 & 3).36

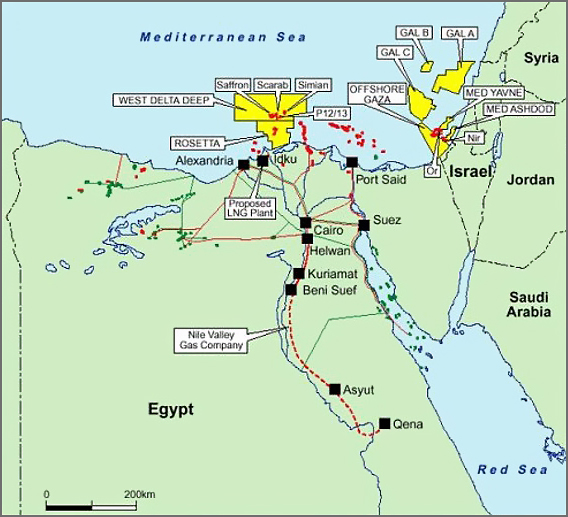

Map 2. Israel and Areas of Palestinian Authority

Source: Michel Chossudovsky. War and Natural Gas: The Israeli Invasion and Gaza’s Offshore Gas Fields. Global Research, August 10, 2014. This map is not an official United Nations map, it is shown only for illustration purpose.

These various offshore installations are also linked up to Israel’s energy transport corridor, extending from the port of Eilat, which is an oil pipeline terminal, on the Red Sea to the seaport – pipeline terminal at Ashkelon, and northwards to Haifa, and potentially linking up through a proposed Israeli-Turkish pipeline with the Turkish port of Ceyhan. Ceyhan is the terminal of the Baku, Tblisi Ceyhan (BTC) Trans Caspian pipeline. “What is envisaged is to link the BTC pipeline to the Trans-Israel Eilat-Ashkelon pipeline, also known as Israel’s Tipline.”37 38

Map 3. The Area Covered by the BG licence and the Gas Fields in Egypt and Lebanon

Source: Michel Chossudovsky. War and Natural Gas: The Israeli Invasion and Gaza’s Offshore Gas Fields. Global Research, August 10, 2014. This map is not an official United Nations map, it is shown only for illustration purpose.

It is now twenty five years (2023) since the drilling of Marine 1 and Marine 2. Since the PNA has not been able to exploit these fields, the accumulated losses are in the billions of dollars. Accordingly, the Palestinian people have been denied the benefits of using this natural resource to finance socioeconomic development and meet their need for energy over this entire period and counting.

The disputes and tensions involving oil and natural gas cannot be separated from the political context that surrounds them, and the fact that the period when the natural gas discoveries were made coincided with a number of important political developments in the region. The political context intersects at many crucial junctures with the oil and natural gas resource developments and thus complicates an already complex political situation. Ignoring these complexities can only rob the analysis of many crucial determinants.

The exploitation of Palestinian natural resources, including oil and natural gas, by the occupying Power imposes on the Palestinian people enormous costs that continue to escalate as the occupation remains in effect. This is not only contrary to international law, but also in violation of natural justice and moral law. To date, the real and opportunity costs of the occupation exclusively in the area of oil and natural gas have accumulated to tens, if not hundreds, of billions of dollars.

The Ben Gurion Canal

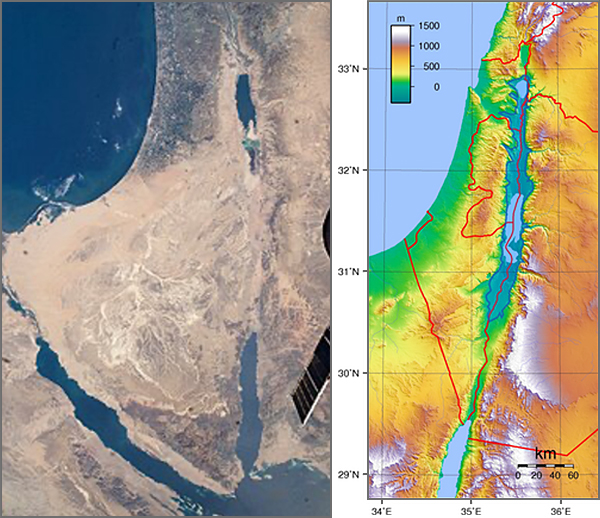

Recently, thanks to the war, the idea of the Ben Gurion Canal project has been revived. A few articles in the media about it have appeared.39 The canal would connect the Gulf of Aqaba (Eilat) in the Red Sea with the Mediterranean Sea and would pass through Israel and end in or near the Gaza Strip (Ashkelon). It has been touted as an Israeli alternative to the Suez Canal that was conceived in the 1960s after Nasser’s nationalization of Suez.

Actually, the first ideas about connecting the Red and Mediterranean seas appeared in the middle of the 19th century by the British who wanted to connect the three seas: Red, Dead and Mediterranean. But given that the Dead Sea is 430.5 meters below sea level; this idea was deemed not feasible.40 The project was laid to rest but came to life following Nasser’s nationalization of Suez. The Americans became interested in the new alternative for several reasons as will be documented here.

In July 1963, H. D. Maccabee of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, under contract to the US Department of Energy, wrote a memorandum exploring the possibility of using 520 underground nuclear explosions to help dig about 250 kilometers of canals through the Negev desert.41 The document was classified as secret until 1993. “Such a canal would be a strategically valuable alternative to the current Suez Canal and would probably greatly contribute to the economic development of the surrounding area,” the declassified document states.42

The idea of the Ben Gurion Canal came to life again at the moment when the so-called Abrahamic Accords between Israel and UAE, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan was announced. On October 20, 2020, the unthinkable happened – the Israeli state-owned company Europe Asia Pipeline Company (EAPC) and the Emirati pipeline company – MED-RED Land Bridge – signed an agreement on the use of the Eilat-Ashkelon oil pipeline to transport oil from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean.43

On April 2, 2021, Israel announced that work on the Ben Gurion Canal was expected to begin by June 2021. However, this did not happen given the status of Gaza as a Palestinian enclave ruled by Hamas. Many analysts interpret the current Israeli re-occupation of the Gaza Strip as something that many Israeli politicians have been waiting for in order to revive the old project.44 The project was named after the first prime minister of Israel, the “founding father of the State of Israel”, David Ben-Gurion.

When the planned route is considered in more detail, it can be seen that the canal starts at the southern edge of the Gulf of Aqaba, from the port city of Eilat near the Israeli-Jordanian border and continues through the Arabah Valley for about 100 km between the Negev Mountains and the Jordanian highlands. It then turns west before the Dead Sea, continues through a valley in the Negev mountain range, and then turns north again to bypass the Gaza Strip and join the Mediterranean Sea in the Ashkelon region. This is not the shortest distance, however, nor is in the optimum geological structure away from the sandy terrain of Negev. Going into Gaza, guarantees the shortest distance advantage as well as the rocky terrain. These advantages are being cited as crucial reasons for the current genocide Israel is perpetrating in Gaza.

The Suez Canal

The importance of the Suez Canal for the world economy cannot be exaggerated. The Suez Canal was opened in 1867 and made it possible to shorten the shipping route between Europe, Africa and Asia, by at least three weeks.45 Instead of sailing around the southern coast of Africa (Cape of Good Hope), ships can use the Suez Canal as a faster and more economical route. The canal is crucial for transporting oil and gas from the Middle East region to European and Far Eastern markets and grain, industrial products and equipment from European and Far Eastern markets to the Middle East and North Africa.

About 18,000 ships pass through Suez annually and transport 12% of world trade. Maritime transport through Suez plays a key role in the world economy as it supports international supply chains and stimulates economic growth in connected continents. The Suez Canal is Egypt’s most valuable economic project, which in the fiscal year 2022-23, achieved record revenues of an estimated $9.4 billion (US dollars) or about 2% of Egypt’s GDP.

The New Channel Characteristics

Although a third longer than the Suez Canal, the Ben-Gurion Canal would be more efficient because, in addition to being able to accommodate a larger number of ships, it would enable the simultaneous two-way navigation of large ships through the design of two canal arms. Unlike the Suez Canal, which is located along sandy shores, the Israeli canal would have rocky walls that require very little maintenance. Israel is planning to build small towns and tourist hubs, hotels, restaurants and cafes along the canal.

Each proposed branch of the canal would have a depth of 50 meters and a width of about 200 meters. It would be 10 meters deeper than Suez. Large ships with a length of 300 meters and a width of 110 meters, which is the current size of the world’s largest ships, could pass through the new canal.

The construction of the canal would take 5 years and involve 300,000 engineers and technicians from all over the world. The estimated cost of construction is put between $16 and $55 billion dollars. Israel should earn $6 billion dollars annually. Whoever controls the canal, and apparently it can only be Israel and its allies (primarily the USA and Great Britain), will have a huge influence on the international supply chains of oil, gas, grains, but also on world trade in general.46

The Importance of the Gaza Strip for the Canal

The original plan for Ben Gurion Canal did not involve cutting through the Gaza Strip, but if Gaza were to be razed to the ground and the Palestinians displaced, a scenario that Israel is implementing now, it would help Israeli planners cut costs, shorten the route of the canal and ensure it is constructed within the rocky terrains of Gaza. But even if the canal would not end in the Gaza Strip itself, it is hard to believe that the Israelis would build it near a Palestinian territory such as Ashkelon. The canal’s distance of only a few tens of kilometers from the Gaza Strip would make it very vulnerable and subject to Palestinian rockets, howitzers, drones and other devices. That is why a basic prerequisite for the construction of the canal is the Israeli military control of the Gaza area. Given these basic reasons it is difficult to dismiss this Israeli objective as a serious factor in what is driving Israeli genocide in Gaza.

Israel has had strong motivations to dig its own canal between the Red and Mediterranean seas because it has been denied the use of the Suez Canal by Egypt on a number of occasions. Since the creation of the State of Israel in 1948 and the defeat of the Arab states in the First Israeli-Arab War of 1948-1949 until the Suez Crisis of 1956, the Straits of Tiran and the Suez Canal remained closed to Israeli shipping. The Suez Canal was closed in 1956-1957 due to the Second Israeli-Arab War and the nationalization of the canal, which was successfully carried out by President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Although the Suez Canal opened in 1957, Egypt continued to block Israeli ships because it did not recognize the State of Israel. During the ten years from 1957 to 1967, only one Israeli-flagged ship and four foreign-flagged ships arrived at the port of Eilat each month. Between 1967-1975 due to the Second, Third and Fourth Israeli-Arab wars as well as the consequent Arab oil embargo, Suez was closed again. Then Israel’s ability to trade with Africa and Asia (especially importing oil from the Persian Gulf) was severely hampered.

This situation was dramatically changed under President Sadat who signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1979 and later on by President el Sisi yielding Egypt’s sovereignty and then reversing the decision over the two islands of the straits that control passage to the Gulf of Aqaba. In either case Israel has been guaranteed full passage through the straits. The question now for Egypt how would react to the Israeli plans to replace the Suez Canal.

President el-Sisi may soon regret putting his trust in Israel and Western governments above the well-being of the two million Palestinians in Gaza. Egypt, apart from formally condemning the mass crimes committed by Israeli forces against the civilian Palestinian population, has done little to prevent Israeli wrongdoing. Benjamin Netanyahu has repeatedly expressed support for the idea of the canal along with the idea of building a high-speed railway from Eilat to Beersheba and other Israeli locations and a land bridge connecting Dubai to Israeli main cities.47

The Economic Motives of the West for Creating an Alternative to the Suez Canal

The new Canal has the backing of the Western powers, the USA and the European Union. The Western motives to create alternatives to Suez are not much different than Israel’s. First, the channel is narrow and shallow and can become blocked very easily. In March 2021, the Suez Canal was blocked for six days due to the container ship Ever Given, which got stuck in the middle of the waterway due to strong gusts of wind and thus blocked traffic. The blockade of one of the world’s busiest trade routes has significantly slowed trade between Europe, Asia and the Middle East. At least 369 ships were waiting in line to pass through the canal with goods worth $9.6 billion. Ports, shippers, freight forwarders, factories, supermarkets, governments and other stakeholders have suffered huge losses. Technical problems; however, are less important than the geopolitical and strategic objectives, particularly those that have come up following the Ukraine-Russian war and tensions with China.

The West does not want to depend on a channel controlled by Egypt, with some ties to the Russian Federation and China, which the West consider them major security threats. Earlier this year, Egypt is slated to become a full member of BRICS from January 1st 2024. The West does not want Egypt directly, nor Russia and China indirectly, to have exclusive control over world trade.

The Silk Road and the New Indo-Saudi Trade Route to Bypass Iran

The Americans and their partners have treated with suspicion and disapproval the Chinese New Silk Road megaproject, in which Egypt has an important role. In 2014, Beijing and Cairo signed the “Strategic Partnership Agreement”, agreeing to cooperate in the fields of defense, technology, economy, the fight against terrorism and cybercrime. Actually, during Xi Jinping’s visit to Egypt in 2016, another 21 agreements were signed, including a contract for 15 billion dollars of Chinese investment in various projects. Infrastructure projects in Egyptian cities have attracted the special attention of Chinese investors. According to China’s ambassador to Cairo, Liao Liqiang, the New Silk Road is closely linked to Egypt’s Vision 2030 – the ambitious development plan launched by President el-Sisi. From 2017 to 2022, Chinese investment in Egypt increased by 317%. During the same period, US investment in Egypt decreased by 31%. Trade between the two countries is about 20 billion dollars.48

The US has brought Saudi Arabia together with India, UAE and Israel to develop a trade route between the Arabian Gulf and South Asia, a rival to a similar project that involves Iran and China. US and her partners are planning a massive infrastructure deal that could reconfigure the landscape of trade in the Eurasia region, linking Middle Eastern countries by a network of railways and connecting to India through shipping lanes, bypassing Iran, Lebanon, Turkey in trade routes from Asia to Europe through Israel.

Also included in this project is the United Arab Emirates and Europe where the plans for sweeping, multi-national ports, road bridges and rail links are being made that would potentially counter China’s growing influence through the Belt and Road global initiative.President Biden went to the G20 meetings in India recently where he pitched Washington as an alternative partner and investor in developing countries, especially in the Indo-Pacific region. According to The Brookings Institution, “China’s growing role in the Middle East is positioning the rising superpower in direct confrontation with shifting US interests in the domains of energy security, Israel, and Iran.”49

The new project is seen as a part of the Biden administration’s mega deal that would have Saudi Arabia recognize Israel. The strategic concept of the “Indo-Abrahamic Alliance” has laid the framework for the formation of the I2U2 group, a grouping of India, Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States.50

The main objective from this deal for the US is the realization of the potential deal between Israel and Saudi Arabia after the administration of then-President Donald Trump reached similar agreements between Israel and Morocco, Sudan, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates.

The US is touting the advantages of the project which could reduce shipping times, costs, the use of diesel and make trade faster and cheaper, potentially making Iran redundant in the transit of goods in the region as the main lure for advancing this project. On the superficial level this project is touted as a trade creation project among the lured group of countries that the US is bringing together under its wings to counter the Chinese Silk Road project. In essence it is shaping up as a trade diversion project that is trying to position India as an alternative to China and to promote “normalizing” the relations of Israel with Saudi Arabia side stepping Iran, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria and Turkey. The core objectives of the project are political that seek the deepening of the chasm between India and China, normalizing relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia and further isolating and even punishing Iran, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey.

On the other hand, Iran and China together with Russia are trying to undo this project with a measure of success. The Gaza war and the indiscriminate bombing and destruction used by Israel as well as the stalemate in the Ukraine-Russia war are undermining the Biden’s administration plans and desires. In an article last year in Tehran’s Time Iran has suggestedthat the Russian invasion of Ukraine, “despite its grave consequences for many countries, has presented Iran with a golden opportunity to realize the long-awaited goal of becoming the global transit hub it once was,” referring to the Silk Road, an ancient network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century that span over 6,400 kilometers (about 3976.78 mi). The war in Gaza has also made it difficult for Arab countries that normalized relations with Israel to pursue further normalization steps if not scrapping these agreements altogether. All this, of course, is a thorn in the side of American policymakers who are looking for alternative ways to block China and normalize Israeli-Arab relations.

Conclusion

The events on October 7, 2023 may have been a “surprise” to Israel’s political and military officials, it should not have been unexpected. Eruptions of violence have well-known causes; they are no secret. Human rights organizations (Israeli, Palestinian, American and international) and UN officials, parliamentarians and governments around the world have long warned that Israel’s long standing denial of freedom and equality for Palestinians would continue sparking cycles of violence.51

More than 2 million Palestinians are in Gaza, locked into an open-air prison. The international community has done nothing to stop Israel’s blockade or to stop the most recent extremist government’s annexation of Palestinian land and turning a blind eye to 600 events of settler violence against native Palestinian villages in the West Bank so far this year (2023). Israeli ministers made daily provocative statements about Al Aqsa mosque and Israeli soldiers attacked worshipers praying there. Generations of Palestinians, 80 percent of them refugees, have grown up in the teeming, impoverished Gaza Strip, one of the most crowded pieces of land on Earth. Since Israel besieged Gaza in 2007, most of them have never been allowed to leave the walled-in, military-guarded Strip, have never glimpsed the West Bank or Jerusalem, let alone 1948 Israel, and certainly not the wider world. Unemployment rates are astronomical and work permits are hard to find and even humanitarian and medical visits are denied.52

It is also not surprising that Israel would seek to make Gaza uninhabitable or unlivable space, the economic stakes in gas, the new Canal and the new trade route are too high not to attract Israeli interests and designs. Colonial exploitation of the colonized nations is well documented and no one should be surprised given the Israeli record of commandeering Palestinian resources and markets. The illegal Israeli occupation of Palestine has been very profitable for Israel so much so that it is not at all surprising to argue that this war is about gas, oil, trade routes and colonial economic advantages and exploitation.53 It is calling into question international inaction and the neglect of a just solution to the Palestinian Question that are further alienating the peoples of the Middle East from their governments and from the complicit west. The guns may lay silent soon but the reverberations of this war will last for a long time to come.

References

- Yessina Funes.“This Genocide is about Oil.”Atmos. November 29, 2023. https://atmos.earth/this-genocide-is-about-oil/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/15/world/middleeast/israel-gaza-war rhetoric.html.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/10/opinion/israel-gaza-genocide-war.html, and https://mondoweiss.net/2023/11/influential-israeli-national-security-leader-makes-the-case-for-genocide-in-gaza/,

- https://www.timesofisrael.com/far-right-minister-says-nuking-gaza-an-option-pm-suspends-him-from-cabinet-meetings.

- Yvonne Ridely. An alternative to the Suez Canal is central to Israel’s genocide of the Palestinians. Middle East Monitor. November 5, 2023.

- Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the Levant Basin Province, Eastern Mediterranean https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2010/3014/pdf/FS10-3014.pdf

- R. H. Coase. 1960. The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics.1:1-44. Ronald Coase won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1991 for this theorem.

- This fact also applies to Lebanon, Syria, Egypt and Cyprus.

- This section is taken from Atif Kubursi. 2019. “Occupation and the Economic Cost of the Unrealized Palestinian Oil and Gas Potential.” Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

- Journal of Palestine Studies 25, no.2, (Winter 1996), Pp: 123-40.

- Anais Antreasyan. Gas Finds in the Eastern Mediterranean: Gaza, Israel, and Other Conflicts. Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. XLII, no. 3 (Spring 2013). A good part of this section is extensively based on this article.

- “Israel Waives Right to Drill Gas in Gesture to Palestinians on the Eve of the Summit.” Ma’ariv July 7, 2000.

- Consolidated Contractors International Company (CCC) owned by Lebanon’s Sabbagh and Koury families.

- November 27, 2000. Associated Press News Archive, http://www.apnewsarchive.com/2000/Arafat-Natural-Gas-Good-for-Economy/id-428946bb0fle30805e3cb3bdeb51e031.

- http://www.bg-group.com/OurBusiness/WhereWeOperate/PagesAreasofPalestinianAuthority.aspx.

- Lior Baron. “British Gas Meets PA on Deal with Israel.” Globes (Israel), April 11, 2007.

- Middle East Economic Digest, Jan 5, 2001.

- Lior Baron. “British Gas Meets PA on Deal with Israel.” Globes (Israel), April 11, 2007.

- William Orme. New York Times September 15, 2000. https://events.nytimes.com/learning/students/pop/000915qodfriday.htm.

- David Hayoun. “British Gas Offered IEC Lower Price than Egypt in 2000,” Globes (Israel) July 27, 2004.

- David Hayoun. Ibid.

- Lior Greenbaum and David Hayoun. “British Gas. We won’t Develop Gaza Field Without Israeli Contracts.” May 23, 2002.

- Ibid.,

- Lior Baron. “British Gas Meets PA on Deal with Israel,” Globes (Israel). April 11, 2007.

- Marian Houk. “Six Months of Negotiations May Open Way to Long Term Israeli Deal to Buy Gaza Gas.” Al-Mubadara May 26, 2007.

- Xinhua General News Service. “Hamas to Change British Gas Contract over Gaza Gas.” June 26, 2007.

- Lior Baron. “Yaalon: Cancel British Gas Deal. It Might Finance Terrorism.” Globes (Israel), September 21, 2007.

- Marian Houk. “Six Months of Negotiations May Open Way to Long Term Israeli Deal to Buy Gaza Gas.” Al-Mubadara May 26, 2007.

- Ibid.

- Member of Knesset Gilad Erdan, Address to the Knesset on “The Intention of Deputy Prime Minister Ehud Olmert to Purchase Gas from the Palestinians When Payment Will Serve Hamas,” March 1, 2006, quoted in Lt. Gen. (ret.) Moshe Yaalon, “Does the Prospective Purchase of British Gas from Gaza’s Coastal Waters Threaten Israel’s National Security?” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, October, 2007.

- “Barak Ravid, Operation “Cast Lead”: Israeli Air Force strike followed months of planning, Haaretz, December 27, 2008.

- Globes (Israel) online- Israel’s Business Arena, June 23, 2008.

- Michel Chossudovsky. “The War on Lebanon and the Battle for Oil,” Global Research, July 23, 2006 and Felicity Arbuthnot, Israel: Gas, Oil and Trouble in the Levant. Global Research, December 30, 2013.

- Globes (Israel), November 13, 2008.

- Globes Nov. 13, 2008.

- Michel Chossudovsky. “The War on Lebanon and the Battle for Oil,” Global Research, July 23, 2006 and Felicity Arbuthnot, Israel: Gas, Oil and Trouble in the Levant. Global Research, December 30, 2013.

- Michel Chossudovsky. “The War on Lebanon and the Battle for Oil,” Global Research, July 23, 2006. And Michel Chossudovsky.War and Natural Gas: The Israeli Invasion and Gaza’s Offshore Gas Fields. Global Research, August 10, 2014

- Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline. The BTC pipeline is an oil pipeline, which opened in June 2005, and runs through Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. Oil giant BP is the lead member of the BTC consortium.https://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan_(BTC)_pipeline

- Matija Seric. “The Ben Gurion Canal: Israel’s Revolutionary Alternative to Suez-Analysis.” Eurasia. November 29. 2023. https://www.eurasiareview.com/17112023-the-ben-gurion-canal-israels-potential-revolutionary-alternative-to-Suez-analysis. and Sargon, Naram (28 March 2021). “السفينة الانتحارية ومحاولة اغتيال قناة السويس .. الرومانسية الناصرية والحلم الساداتي” [The suicide ship and the Suez Canal assassination attempt … Nasserist romance and the Sadatian dream]. serjoonn.com. “Ship crisis revives Russian, Israeli talk of alternatives to Suez Canal”. The Arab Weekly. March 30, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- Ibid.,

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Plowshare and also https://www.businessinsider.com/us-planned-suez-canal-alternative-israel-blast-with-nuclear-bombs-1960s-2021-3.

- Ibid.,

- https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN275151/, but was later shut down by Israel and https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/israels-environment-ministry-blocks-oil-pipeline-deal-with-uae-2021-12-16/

- Yvonne Ridely in an article in the Middle East Monitor and a few other analysts have raise the question that the Israelis knew about Hamas plans on October 7, 2023 but allowed them to happen in order to mount their re-occupation plan. Yvonne Ridely. An alternative to the Suez Canal is central to Israel’s genocide of the Palestinians. Middle East Monitor. November 5, 2023.

- The distance from Mumbai, India to London around Africa cover 10,702 nautical miles, whereas it is only 6,279 nautical miles through the Suez Canal (sea-distances.org).

- Matija Seric. “The Ben Gurion Canal: Israel’s Revolutionary Alternative to Suez-Analysis.” Eurasia. November 29. 2023. https://www.eurasiareview.com/17112023-the-ben-gurion-canal-israels-potential-

- Matija Seric. Ibid.

- Matija Seric. Ibid.

- Ghazal Vaisi. “Belt and Road Initiative, China’s Great Game.” January 23, 2022. https://www.iranintl.com/en/202201234628

- https://www.iranintl.com/en/202309083583

- Phyllis Beenis. 2023. October 7 2023 and its aftermath. Unpublished

- Phyllis Beenis. 2023. Ibid.

- Several recent UNCTAD studies in 2014, 2015 and 2019 have documented this fact. United Nations General Assembly. Committee on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People. A/70/35, October 6, 2015 and United Nations General Assembly. (2016). Economic Costs of the Israeli Occupation for the Palestinian People. A/71/174, July 21, 2016.