The events of 9/11 left many Americans shaken. Into this atmosphere of depression and upset came worries about anthrax.[1] As will be explained later, worries about anthrax actually preceded October 3, the date of confirmation of the first anthrax attack. That is, people had already become concerned about anthrax before the news about the anthrax attacks became public. Many began taking Ciprofloxacin, the antibiotic favored at the time for anthrax, and there was open discussion of the need for a publicly available anthrax vaccine. By September 26, even though, according to the official story, no one but the perpetrators knew anthrax had been released in the mails, there were open discussions in the press of an “anthrax scare.”[2] After the death of Robert Stevens on October 5, the fears had a sound basis and grew rapidly.

The U.S. media did not hesitate to make anthrax fears a major theme. In fact, they considered fears of anthrax almost as newsworthy as anthrax itself and reported on them repeatedly. By reporting on these fears, they participated, of course, in their spread. “Anxiety” was probably the most common term (“Anthrax Anxiety at Home,”[3] “widespread anxiety in New York,”[4] “Anxiety Grows in South Florida,”[5] “Anxiety Over Bioterrorism Grows”[6]), but there were also references to “a frightened public,”[7] “rising public concern,”[8] “panicky citizens”[9] and “hysteria.”[10] There were also references to “jitters”[11] and “nervousness.”[12] Immediately after the death of Robert Stevens, the Washington Post reported that “jittery” citizens were “on their knees begging for drugs.”[13] On October 10 the appropriately named Darryl Fears reported in the same newspaper that after law enforcement agencies put the nation in a state of high alert and Ashcroft asked Americans to maintain “a heightened state of awareness,” the result was increased fear.[14] Along with the demand for Cipro, it appears, there was now a demand for gas masks.[15] Soon (Oct. 15) it was reported that the “anthrax scare” was spreading around the world.[16] Eventually (Oct. 18) the reading public was informed that “the fear of anthrax has become inescapable,”[17] and shortly thereafter—not long before the final Congressional votes on the Patriot Act—Americans were said to be experiencing “primordial terror”[18] in “a national anxiety attack.”[19] It did not take long for journalists to come up with a clever aphorism: anthrax is not contagious, but fear of anthrax is.[20]

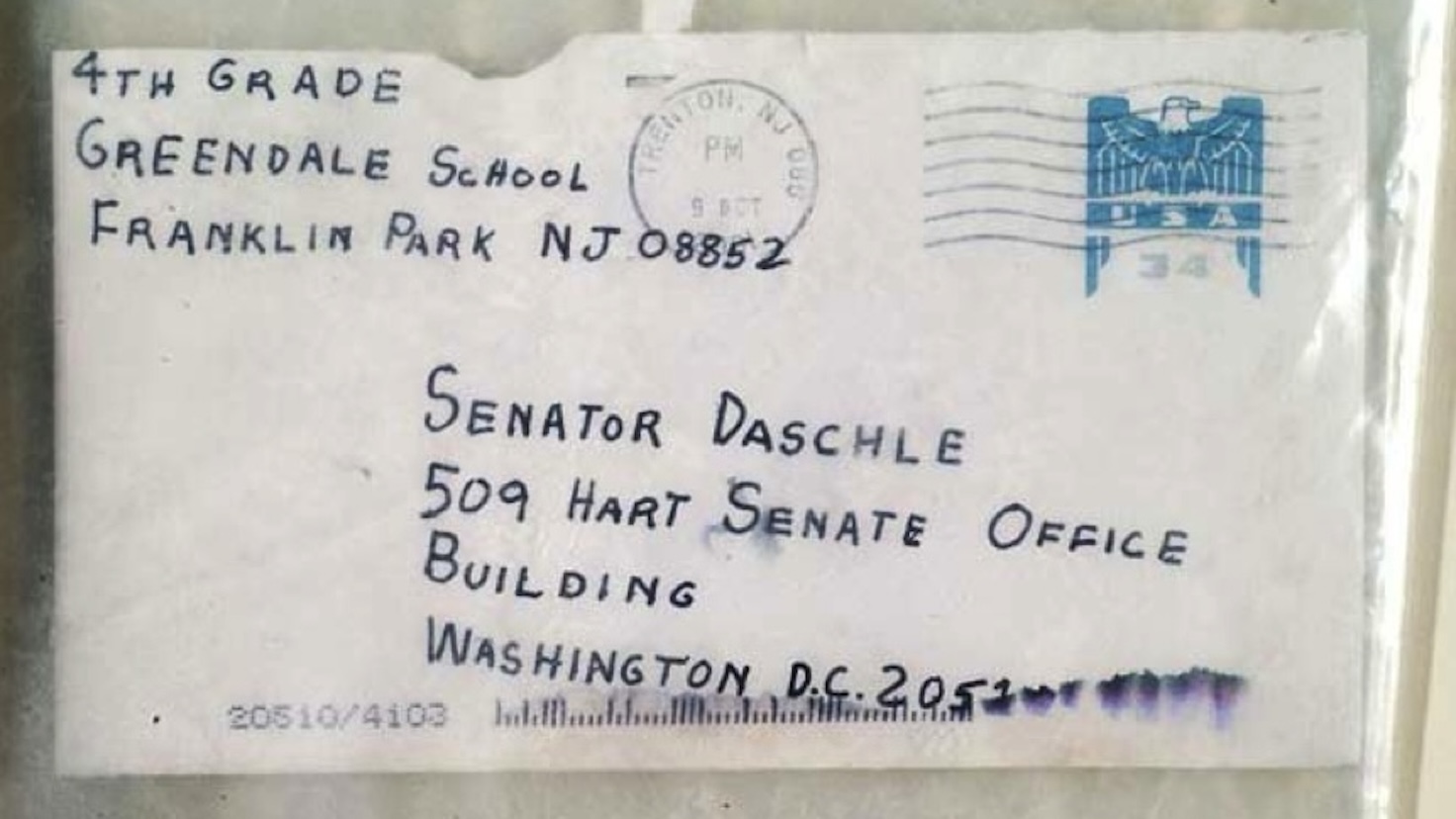

But ordinary citizens were not the only ones who had been targeted. The U.S. Congress was in the crosshairs as well. The targeting of Congress appeared to have started on 9/11. Senator Tom Daschle recalls being at the U.S. Capitol when he and other members of Congress were interrupted by the news of the 9/11 attacks.[21] They began watching events unfold on television like everyone else. Daschle says that not long after the incident at the Pentagon (roughly 10:38 a.m.) a Capitol police officer ran into the room. “Senator,” he said, “we’re under attack. We have word that an airplane is heading this way and could hit the building anytime. You need to evacuate.”[22]

The view that the plane that was ultimately destroyed in Pennsylvania (“Flight 93”) was headed for the Capitol was common at the time. For members of Congress the existence of this plane signified that they had been the target of a direct attack aimed at mass casualties and that only good fortune had saved them.

Daschle remembers that “the scene was total chaos.” “The halls,” he says, “were filled with fear and confusion.” It was “the first time in history that the entire United States Capitol had been evacuated.”[23] With no procedure in place for this particular type of attack, senators and representatives scattered. Daschle, as Senate Majority Leader, was put by his security detail into a helicopter and flown to a “secure location.” Later, in the evening, some members of Congress drifted back to the Capitol, where the assembled crowd stood on the steps of the Capitol, listened to speeches, and broke into a spontaneous rendition of God Bless America.[24]

That the unity created by threat and war was already taking hold is clear from Daschle’s comments: “we turned to one another like long-lost members of a large family and embraced.”[25] Of the day as a whole, he remarks: “I can’t think of a time in my life when I have witnessed such deeply felt unity and connection among our countrymen.”[26]

Polls soon confirmed Daschle’s observations. A sense of national unity and pride increased, support for the executive dramatically climbed, and citizens confirmed a willingness to surrender some of their civil liberties as part of the sacrifice that seemed demanded of them.[27]

From that violent day in September until the anthrax attacks were finished, there was no time when Congress was able to feel safe. After 9/11 the Capitol was closed to the public and “surrounded by yellow police tape and concrete barriers.”[28] The danger of further violent incidents, especially directed at Congress, became a major media theme during the remainder of the fall.

On October 2, a day before the diagnosis of Stevens’ disease, U.S. intelligence sources told Congress that if the U.S. conducted military strikes against Afghanistan (which it had every intention of doing and which it began doing five days later) there was a “100% chance” of a terrorist attack by Bin Laden’s group. Expected targets, said the intelligence officials, included symbols of culture such as “government buildings in Washington.” Biological or chemical weapons were said to be leading worries.[29]

On October 6, after Stevens had died but before his death was known to have been the result of an intentional criminal act, the Washington Post reported that “many of the nation’s premier monuments” (this certainly would have included key Washington locations) were “targets of opportunity” for biological and chemical terrorism.[30] [

On October 9 it was noted that terrorist retaliation was expected now that the bombing of Afghanistan had begun, and that Congress was considered a prime target. Members of Congress were advised to hide their identities. “On Capitol Hill members of Congress were discouraged from wearing their congressional pins when they are away from the Capitol.” Moreover, they were “advised for security reasons to avoid using license plates or anything else that would identify them as members of Congress.”[31]

On October 10 it was learned that “concern over an attack on the U.S. Capitol” was resulting in a variety of proposals for road closings and barriers. “Washington is considered one of the leading targets for terrorists.”[32] Funds were sought for emergency preparedness.[33] On the same day it was learned that Capitol police were barring trucks and buses from proximity to the Capitol.[34]

On October 11 the FBI issued its most specific threat warning since 9/11, saying that “additional terrorist acts could be directed at U.S. interests at home and abroad over the ‘next several days.’” The warning included all types of terrorist attacks and specifically mentioned the Capitol as a possible target. Mention was made of danger from crop-dusters, raising the possibility of biological or chemical attacks by this means. Moreover, Ari Fleischer “said the decision to issue the alert is consistent with Bush’s insistence that federal authorities immediately release information about anthrax cases in Florida.”[35]

This FBI warning of October 11 came directly before the crucial discussion and vote in Senate on the Patriot Act. The bill was passed late in the evening of October 11.

The Strategy of Tension?

Anxiety, fears, warnings by intelligence agencies: these dogged members of Congress throughout the fall of 2001. Were they the result of international terrorism of the al-Qaeda variety? Or did they issue from the heart of the U.S. state itself? If the latter, could they have come from a group that was intentionally intimidating Congress? Although the term “terrorism” would still be applicable in this case, more precision can be achieved by employing the academically recognized concept of “strategy of tension.”

For several decades in post-WWII Europe a program of fear and intimidation was mounted by members of European security services working with non-state and international allies, including the CIA and NATO. The most common name for the general program is GLADIO, meaning “Sword,” the name originally given to the Italian version of the program. The strategy of tension was central to GLADIO. GLADIO scholar Daniele Ganser explains it as follows:

In its essence, the strategy of tension targets the emotions of human beings and aims to spread maximum fear among the target group. ‘Tension’ refers to emotional distress and psychological fear, whereas ‘strategy’ refers to the technique of bringing about such distress and fear. A terrorist attack in a public place, such as a railway station, a market place, or a school bus, is the typical technique…After the attack—and this is a crucial element—the secret agents who carried out the crime blame it on a political opponent…[36]

The strategy of tension as a subcategory within psychological warfare was employed in post-WWII Europe both to arouse antagonism towards selected groups and to induce the fearful population (as well as targeted membersof elected state bodies) to take refuge in, and cede power to, the state’s security apparatus. As a powerful tool of the political Right, it was employed to discredit members of the Left and, in some countries, to put in peril the project of liberal democracy. It served both to arouse hatred toward a designated and framed Other and to achieve public consent to the reduction of the civil liberties of the population on which it was unleashed.

The present book makes the case that the 2001 anthrax attacks were products of a domestic conspiracy initiated by parties in high positions within the U.S. state. I contend that the conspirators utilized the strategy of tension while framing a Muslim Other (al-Qaeda and Iraq), to push the American population and its elected representatives into a form of civic self-immolation: frightened, they ceded liberties and powers.

Passing the Patriot Act

In the case of the Patriot Act, our investigation requires attention to details of targets and timing. As a brief review of the passing of the Patriot Act will show, the peculiar convergence, already noted, of the October 11 FBI warning and the passing of the Patriot Act by Senate, is merely one instance of such convergences.

We may begin with two questions about the anthrax attacks on Congress. If the anthrax attacks were products of the strategy of tension, why target the Senate, as opposed to the House of Representatives? And, why target two particular senators—Tom Daschle and Patrick Leahy?

There is no mystery as to why the Senate was targeted rather than the House of Representatives. In the House the Republicans had a comfortable majority. It was almost impossible for the Patriot Act to fail in the House. But the Senate, through a number of accidents, had ended up with a Democratic majority. It was a majority of one, but still a majority. If Democrats decided to reject the bill, and if they voted as a bloc, the bill would fail. The Senate vote was essential: both chambers had to pass the bill before it could become law.

The question of why these two senators were targeted is only slightly more complicated. Tom Daschle (Democrat, South Dakota) was Senate Majority Leader. In his role as, arguably, the most powerful Democrat in the Senate, Daschle would have been expected to help direct debate in the Senate and to establish a timetable for the discussion and passing of the new legislation supposedly crafted to deal with terrorism. During this process he would also be expected to consult with both the opposition party and members of the executive.[37] Given the Democratic majority in the Senate, he was crucial to the passing of the new legislation.

Patrick Leahy (Democrat, Vermont) was Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. This committee is a standing committee of the Senate, which has as one of its mandated duties the consideration of all legislation relating to civil liberties.[38] Leahy’s committee was only one of several that reviewed the proposed Patriot Act, but it was the most important given the direct relationship of the legislation to civil liberties. In fact, Leahy played a central role throughout the discussion and refinement of the bill.

The U.S. Senate is supposed to be a body of “wise elders” and is expected to behave carefully and with deliberation. But under constant bullying by John Ashcroft and other members of the executive branch, this body acted much more quickly than it normally would have with important new legislation. Journalist John Lancaster, for example, noted the “blistering pace of the legislation through Congress” and the extreme dissatisfaction some members of Congress felt after what they judged to be a failure of democratic process.[39]

In one sense, then, given Democratic control of the Senate and the importance of quickly getting these two senators on board, it is obvious why Daschle and Leahy would be key targets of intimidation for anyone wanting the bill passed. The real question is why, given the clear desire of these two senators to cooperate with both the executive and the opposition party, someone would have felt it necessary to intimidate them.

Recall that Daschle felt an overwhelming sense of the unity of the American people after the 9/11 attacks. He was the one who willingly proposed the crucial resolution on the use of force on September 14 that began the process of handing over power to the executive. Reading accounts of these events today, we do not readily conclude that Daschle was an obstreperous figure needing a lethal threat.

Similar things can be said about Mr. Leahy. He believed in the necessity of the Patriot Act and he worked day and night, in consultations with John Ashcroft and other members of the executive, to refine the legislation so that it could be passed with as little delay as possible.

But what may look to us, in retrospect, as passivity in the face of the executive seizure of power may at the time have appeared to the administration as dangerous resistance. Moreover, it is important to bear in mind that although events such as the 9/11 attacks can induce people to sacrifice their civil rights, the effect appears to be time limited.[40] Those wishing to push through draconian legislation will know they must do it quickly, before the psychological effects of the initial event wear off.

While Leahy and Daschle were in favor of some form of the Patriot Act, there were issues over which they drew the line. Inevitably, this slowed down the process. To someone concerned to see the legislation enacted promptly there would always linger the possibility that the Senate, under the guidance of people committed to civil liberties, might begin acting in a genuinely deliberative way and reject or gut the new legislation, as Congress had done when similar and related legislation had been put forward after the Oklahoma bombing of 1996.[41]

From this perspective, it would seem that October 2 was the day the two senators put themselves at risk of death. Here is a quick review of events leading to that day.

On Monday, September 17, Attorney General John Ashcroft first publicly announced he would be sending an “antiterrorism” proposal to Congress. He made it clear at that time that he wanted it enacted with blazing speed: “we will be working diligently over the next day or maybe two to finalize this comprehensive proposal, and we will call upon the Congress of the United States to enact these important antiterrorism measures this week.”[42] If Daschle had been shocked by the draft of the use of force proposal that he received on September 12, he was now shocked again. Ashcroft’s draft of the Patriot Act was, it turned out, not even presented to Congress until Wednesday, September 19. Was Congress really supposed to pass this complex, lengthy and extremely important legislation between Wednesday the 19th and Friday the 21st with no significant review whatsoever?[43]

This request went too far. Leahy, wanting to cooperate but unwilling to see Congress “rubber-stamp the anti-terrorism proposals” said that “[i]f the Constitution is shredded, the terrorists win.”[44] He added that he would work hard over the weekend and, with luck, be prepared to have a more acceptable draft ready by Tuesday, September 25, at which time his committee would hold hearings on the bill. Leahy’s tone was positive. He said, according to the Washington Post (September 20), that he hoped “that Congress could send the anti-terrorism measure to President Bush within a few weeks—an expedited schedule that reflects the continuing sense of national emergency.”[45] “A few weeks” was, indeed, a greatly accelerated schedule, but it was not sufficiently accelerated for the Bush administration.

Ashcroft had stressed the continuing emergency and the ongoing pressing danger of terrorism when he announced his bill, and he would reiterate this many times. The need for the rapid passage of the legislation was a constant theme in his speeches during this period.[46]

In Tom Daschle’s words, Ashcroft “attacked Democrats for delaying passage of this bill.” “[I]n this climate of anxiety, the attorney general was implicitly suggesting that further attacks might not be prevented if Democrats didn’t stop delaying.”[47]

Meanwhile, opposition to the bill was rapidly growing, both inside Congress and among a broad variety of civil society groups concerned about the proposed inroads on civil liberties.[48] But the administration kept up the pressure. In an important September 20 speech Bush took the opportunity to mention the importance of the new legislation.[49]

By September 22 rumors of biological terrorism had begun to spread in the mass media, and shortly thereafter the rumors included suggestions that al-Qaeda might conduct mass attacks with crop-dusting planes.[50] This added to the atmosphere of tension.

But the legislation had run into trouble. On Monday, September 24, it came in for criticism in committees of both the Senate and House. Leahy kept working to construct an acceptable bill by Tuesday, September 25, while Ashcroft kept pushing. “Terrorism is a clear and present danger to Americans today,” he said, adding that “each day that so passes is a day that terrorists have an advantage.”[51] On September 25 questions and criticisms continued to arise, so at this point Bush and Cheney entered the fray. Bush said: “we’re at war…and in order to win the war, we must make sure the law enforcement men and women have got the tools necessary.” Cheney, at a lunch with Republican senators, asked them to do their best to get the legislation passed through Congress by October 5.[52]

The rumors of biological attacks continued to spread over the next few days.[53] A front page article in The New York Times on September 30 was entitled, “Some Experts Say U.S. Is Vulnerable To a Germ Attack.”[54] Anthrax was mentioned as a worry. In truth, anthrax letters were at that time already in circulation, but, according to the official account, no one but the perpetrators knew about them.

Indeed, on September 30 a major administration offensive began, with the aim of putting pressure on Congress

to meet Cheney’s new deadline of October 5. Among members of the executive branch stepping forward were Attorney General John Ashcroft, White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, and Secretary of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson.[55] Ashcroft, appearing on CBS’s Face the Nation, referred to the “likelihood of additional terrorist activity,” and he made it clear that the terrorist activity could be expected to come from the same sources as the 9/11 attacks: “It’s very unlikely that all of those associated with the attacks of Sept. 11 are now detained or have been detected.” Card said that “terrorist organizations, like al Qaeda…have probably found the means to use biological or chemical warfare.” Rumsfeld stated that terrorists could be equipped by their state sponsors with weapons of mass destruction. Tommy Thompson tried to strike a less distressing note, reassuring viewers on CBS’s 60 Minutes, “that we’re prepared to take care of any contingency, any consequence that develops for any kind of bioterrorism attack.”

ABC’s Peter Jennings, noting the difference in tone between apparent alarmists such as Card and those such as Thompson who sought to reassure the public, remarked (ABC News, October 1, 2001): “There’s been some confusion for the public in the last 48 hours about whether the country should be worried about an attack using chemical or biological weapons.” The program then went on to discuss the federal government’s plans for how to deal with such attacks.

There was nothing subtle about the connection of all the speeches to the bill the administration wanted passed. The first line in the Washington Post’s October 1 article on the topic was: “Bush administration officials said yesterday there will likely be more terrorist strikes in the United States, possibly including chemical and biological warfare, and they urged Congress to expand police powers by Friday [Oct. 5] to counter the threat.”[56]

On the same day as this administration offensive, September 30, photo editor Robert Stevens, on vacation, came down with “flu-like symptoms” and crawled into the backseat of his car to rest, letting his wife take the wheel.[57] He had inhalation anthrax. His illness would be diagnosed on October 3 and he would die on October 5.

The press had carried articles throughout this period about biological attacks and anthrax. On September 28, for example, Rick Weiss of the Washington Post had written of the need to make an anthrax vaccine available to the public. Clinics across the country, he explained, were being swamped with requests for the vaccine.[58]

It is in this context that Leahy and Daschle’s actions of October 2 must be understood. On that day it was determined that the administration’s October 5 deadline would not be met. Both senators were directly implicated in the delay.

The Washington Post (October 3) gave the gist in the title of an important article on the subject: “Anti-terrorism Bill Hits Snag on the Hill; Dispute Between Senate Democrats, White House.”[59] In the article we learn that, “Leahy accused the White House of reneging on an agreement.” The issue was “a provision setting out rules under which law enforcement agencies could share wiretap and grand jury information with intelligence agencies.” Leahy had been under the impression that his negotiations with the White House had produced an acceptable compromise; suddenly he discovered the compromise had been rejected. As Leahy balked, “Attorney General John D. Ashcroft accused the Democratic-controlled Senate of delaying legislation that he says is urgently needed to thwart another terrorist attack.” The Senate, Ashcroft said “was not moving with sufficient speed.” “Talk,” he complained, “won’t prevent terrorism,” adding that he was “deeply concerned about the rather slow pace” at which the legislation was moving. Daschle, reports the article, supported Leahy. Although he was committed to seeing the legislation passed quickly, Daschle said that “he doubted the Senate could take up the legislation before next week.” In other words, the October 5 deadline would not be met. Leahy and Daschle were the only Democratic senators mentioned in the article.

Although this small act of resistance may seem trivial to us today, Republican senator Orrin Hatch, supporting the administration, noted at the time: “It’s a very dangerous thing.”[60]

Apparently it was, indeed, a very dangerous thing. Shortly after the October 5 deadline passed with no enactment of the bill, letters containing anthrax spores were sent to Senators Leahy and Daschle. These letters were put in the mail sometime between October 6 and 9.[61]

It could be argued that mailing letters to the two senators was unnecessary since a compromise had been worked out on October 3-4.[62] But the executive was not seeking a compromise with this or that committee or with a few Democrats: it wanted the bill voted on and enacted without further delay. As it happened, the vote approving the bill in Senate did not take place until October 11, directly after the previously mentioned FBI warning. Even then, the legislation was not secure. The House and the Senate had passed different versions of the bill. The two had to be harmonized, and two separate votes needed to be held on the final version. Only then could Bush sign the final bill into law. The process did not come to a conclusion until October 26 and in the interim Congress would not be permitted to feel secure.

The dramatic action reached its high point with the opening of Daschle’s letter. On October 15, Roll Call, a Washington newspaper dedicated to reporting news related to Capitol Hill, had as its front page headline: “HILL BRACES FOR ANTHRAX THREAT.”[63] Sure enough, it was later that day that Grant Leslie, an intern working for Daschle, opened a letter to the senator to find two grams of spores of B. anthracis along with a text concluding with “ALLAH IS GREAT.”[64] Due to the aerosolized (“floaty”) nature of the anthrax spores, a characteristic not easy to achieve since in nature the spores tend to clump, many people in the Hart Senate building tested positive for exposure. There was general shock as it was discovered the spores, apparently treated in a sophisticated manner, had quickly contaminated the building.

The Hart Senate building had to be closed and the senators with offices there relocated. Much of the work by members of Congress to harmonize the two versions of the Patriot Act was carried out in unsettled conditions—in some cases in temporary quarters with limited computer access by senators writing on pads of paper.[65]

Once again the media concentrated on the anxiety produced: “A handful of anthrax particles sent through the mail to Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle (D-S.D.) has sent Capitol Hill into an orbit of jitters and confusion…”[66]

Colbert King summed up the disturbance to Capitol Hill in an article in the Washington Post on October 27.[67] Noting that an aim of terrorism is “to instill feelings of fear and helplessness in citizens,” he said:

…the perpetrators of the anthrax terror hit pay dirt in Washington. They’ve managed to accomplish what the British tried to generate with their burning of the White House, the Capitol and other government buildings in 1814—what Lee Harvey Oswald couldn’t deliver in 1963—and what the Pentagon attackers sought to but couldn’t provoke on Sept. 11: a sense of vulnerability and danger so great that it disables and fundamentally alters the way the nation’s capital does its business.

“Anthrax,” he added, “caused the House of Representatives to flee town; it closed Senate office buildings: unprecedented actions.”

Finally, on October 26, Bush signed the bill into law. As he did so, he invoked the anthrax attacks as justification for the curtailment of civil rights:68

The changes, effective today, will help counter a threat like no other nation has ever faced. We’ve seen the enemy, and the murder of thousands of innocent, unsuspecting people.

They recognize no barrier of morality. They have no conscience. The terrorists cannot be reasoned with. Witness the recent anthrax attacks through our Postal Service.

Our country is grateful for the courage the Postal Service has shown during these difficult times. We mourn the loss of the lives of Thomas Morris and Joseph Curseen; postal workers who died in the line of duty. And our prayers go to their loved ones…

But one thing is for certain. These terrorists must be pursued, they must be defeated, and they must be brought to justice. And that is the purpose of this legislation.

Receipt of the anthrax letters did not fundamentally change the views of Daschle and Leahy. They had already given their support to the Patriot Act before they received their anthrax letters and they had committed themselves to getting the legislation passed quickly. On October 9 Daschle had said the legislation was “urgently needed” and that it ought to be passed “this week.”[69] He made sure the bill went through. “At the urging of Senate Majority Leader Thomas A. Daschle (D-S.D.), [lawmakers] repeatedly turned aside efforts by Sen. Russell D. Feingold (D-Wis.) to amend the bill to address what he said were its failures to adequately protect civil liberties.”[70]

When the bill was passed in the Senate shortly before midnight on October 11, Feingold stood alone against it.[71]

Leahy said, “Despite my misgivings, I have acquiesced in some of the administration’s proposals because it is important to preserve national unity in this time of crisis.”[72]

The attacks on the United States Congress were a central part of the anthrax crimes. Congress members—intimidated, harassed, driven from their buildings, told not to wear their identification, and exposed to a deadly pathogen—gave in to the executive and acquiesced to its seizure of power.

If this assault on the legislative branch of government was, indeed, authored by members of the executive branch as an instance of the strategy of tension, the implications are enormous.

NSA Domestic Spying

As Congress was being pressured and intimidated, the executive did not wait for passage of the Patriot Act to begin spying on Americans. On December 20, 2013 U.S. federal officials publicly admitted for the first time that George W. Bush, on October 4, 2001, had “authorized sweeping collections of Americans’ phone and Internet data.”[73] On October 5, the NSA General Counsel had pronounced the program legal.[74] Thus began the NSA incursions on civil liberties that were to become well known.

On October 25, 2001 four members of Congress were briefed on the program, the rest of Congress being kept in the dark. The four initiates were Nancy Pelosi and Porter Goss, the Chair and Ranking Member of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence; and Bob Graham and Richard Shelby, the Chair and Vice Chair of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.[75]

James Clapper, Director of National Intelligence, was the one who revealed the information about the October, 2001 initiation of the program. He later said that if American citizens had been asked to approve the domestic spying directly after 9/11 they probably would have done so. “I don’t think it would be of any greater concern to most Americans than fingerprints.”[76] The mistake, he felt, was in not being transparent. But, of course, there is no way of knowing what Americans would have approved if they had been asked. They had not been asked. Moreover, there is no reason to believe Clapper would have made his information public at all if it had not been for a chain of events provoked by the Edward Snowden revelations.

At this time we can only speculate on the precise relationship of the NSA initiative to the anthrax attacks, but it is important to remember that there was a great deal more going on in the U.S. at this time than the trauma from September 11 mentioned in most accounts of NSA spying. There were almost daily warnings by the U.S. administration of further attacks to come; there were people taking Cipro, buying gas masks and attempting to get anthrax vaccines; and, as time went on, there were deaths from anthrax. On October 3, the day before Bush’s signing of the order, Robert Stevens was diagnosed with anthrax. He died the day after the signing. Likewise, two days before the four members of Congress were briefed, two postal workers died of anthrax.

Later, defenders of the secret NSA program (the “Terrorist Surveillance Program”) attempted to defend it as a legitimate interpretation of Section 215 of the Patriot Act. But this, of course, does not hold water. Bush signed the NSA order before the Patriot Act had been approved either by the Senate or by the House of Representatives.

Notes to Chapter 4

- Leonie Huddy, Nadia Khatib, and Theresa Capelos, “The Polls–Trends: Reaction to the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001,” Public Opinion Quarterly 66 (2002).

- Tamar Lewin, “Anthrax Scare Prompts Run on an Antibiotic,” The New York Times, September 27, 2001.

- Serge Schmemann, “An Overview: Anthrax Anxiety at Home, Signs of Progress,” The New York Times, October 16, 2001.

- David Barstow, “Anthrax Found in NBC News Aide: Suspicious Letter Is Tested at Times–Wide Anxiety,” The New York Times, October 13, 2001.

- Jim Yardley, “The Anthrax Investigation: Anxiety Grows in South Florida as Mystery of Anthrax Cases Lingers,” The New York Times, October 12, 2001.

- R. W. Apple, “The Overview: As Anxiety Over Bioterrorism Grows, Bush Promises That the U.S. Will Stay Vigilant,” The New York Times, October 14, 2001.

- “Fears of Anthrax and Smallpox (Editorial),” The New York Times, October 7, 2001.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- David Kocieniewski, “The Jitters: Nervousness Spreads, Though Illness Doesn’t,” The New York Times, October 11, 2001; Richard Jones, “Jitters: These Days, Even Soap Is a Suspicious Powder,” The New York Times, October 18, 2001.

- Kocieniewski, “The Jitters: Nervousness Spreads, Though Illness Doesn’t.”

- Rick Weiss, “Source of Florida Anthrax Case Is Sought; Victim Dies as 50 Investigators Search,” The Washington Post, October 6, 2001.

- Darryl Fears, “Security Crackdown a Mixed Bag; Alert Varies From Calvert Cliffs to Disneyland, From Thorough to Easygoing,” Washington Post, October 10, 2001.

- Don Oldenburg, “Stocking Up in Hopes Of Breathing Easier; Gas Masks May Not Offer Protection,” The Washington Post, October 10, 2001.

- Michael Powell and Peter Slevin, “Detective, Scientists Exposed to Anthrax; FBI Continues to Hunt for Letters’ Origins,” The Washington Post, October 15, 2001.

- Shankar Vendantam, “Bioterrorism’s Relentless, Stealthy March; Confusion and Publicity Help to Heighten Public’s Fear of Attack From Unknown,” The Washington Post, October 18, 2001.

- Dana Milbank, “Fear Is Here to Stay, So Let’s Make The Most of It,” The Washington Post, October 21, 2001.

- “Terror Attacks The Mentally Ill,” The Washington Post, October 23, 2001.

- R. W. Apple, “City of Power, City of Fears,” The New York Times, October 18, 2001; Michael Janofsky, “The False Alarms: Anthrax Fears Appear to Spread, Even Without New Verified Cases,” The New York Times, October 17, 2001; Kocieniewski, “The Jitters: Nervousness Spreads, Though Illness Doesn’t.”

- Daschle and D’Orso, Like No Other Time: The 107th Congress and the Two Years That Changed America Forever, 107 ff.

- Ibid., 109.

- Ibid., 110.

- Ibid., 110 ff.

- Ibid., 118.

- Ibid., 117.

- Morin, “Almost 90% Want U.S. To Retaliate, Poll Finds”; Huddy, Khatib, and Capelos, “The Polls–Trends: Reaction to the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001.”

- Daschle and D’Orso, Like No Other Time: The 107th Congress and the Two Years That Changed America Forever, 125.

- Susan Schmidt and Bob Woodward, “FBI, CIA Warn Congress of More Attacks As Blair Details Case Against Bin Laden; Retaliation Feared If U.S. Strikes Afghanistan,” The Washington Post, October 5, 2001.

- David S. Broder and Eric Pianin, “U.S. Is Still Vulnerable To Attacks, Experts Say; Numerous ‘Targets of Opportunity’ Cited,” The Washington Post, October 6, 2001.

- Eric Pianin, “Ridge Assumes Security Post Amid Potential For New Attacks; FBI Warns Public, Private Entities To Observe ‘Highest State of Alert,’” The Washington Post, October 9, 2001.

- Spencer S. Hsu and Carol D. Leonnig, “Lawmakers Seek Ways To Secure U.S. Capitol; Temporary Street Closings; Pop-Up Barriers Considered,” The Washington Post, October 10, 2001.

- Sewell Chan and Carol D. Leonnig, “City Seeks More Aid For Terrorism Relief; Preparedness, Recovery Help Requested,” The Washington Post, October 10, 2001.

- David A. Fahrenthold and Carol D. Leonnig, “Police Bar Most Buses And Trucks Near Capitol; Sudden Security Move Surprises D.C. Officials,” The Washington Post, October 11, 2001.

- Dan Eggen and Bob Woodward, “Terrorist Attacks Imminent, FBI Warns; Bush Declared Al Qaeda Is ‘On the Run’; Assaults on U.S. Called Possible in ‘Next Several Days,’” The Washington Post, October 12, 2001.

- David Griffin and Peter Scott, eds., 9/11 and American Empire: Intellectuals Speak Out, vol. 1 (Olive Branch Press, 2006), 82. See also Daniele Ganser, “The ‘Strategy of Tension’ in the Cold War Period, Journal of 9/11 Studies, vol. 39, May 2014.http://www.journalof911studies.com/ resources/2014GanserVol39May.pdf

- “Congress of the United States: Senate Majority Leader,” The Free Dictionary: Legal Dictionary, accessed May 22, 2014, http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Senate+Majority+Leader.

- “How Congress Works: Rules of the Senate: Standing Committees,” United States Senate: Committee on Rules & Administration, accessed May 22, 2014, http://www.rules.senate.gov/public/index.cfm?p=RuleXXV.

- John Lancaster, “Anti-Terrorism Bill Is Approved; Bush Cheers House’s Quick Action, but Civil Liberties Advocates Are Alarmed,” The Washington Post, October 13, 2001.

- Huddy, Khatib, and Capelos, “The Polls–Trends: Reaction to the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001”; Kam Wong, “The Making of the USA PATRIOT Act II: Public Sentiments, Legislative Climate, Political Gamesmanship, Media Patriotism,” International Journal of the Sociology of Law 34 (2006): 105–40.

- “History Commons: US Civil Liberties: Patriot Act: April 25, 1996: New Anti-Terrorism Law Passed,” n.d., http://www.historycommons.org/timeline.jsp?timeline=civilliberties&civilliberties_patriot_ act=civilliberties_patriot_act.

- John Ashcroft and Mueller, “Attorney General John Ashcroft Remarks: Press Briefing with FBI Director Robert Mueller” (FBI Headquarters, September 17, 2001), https://w2.eff.org/Privacy/Surveillance/Terrorism/20010917_ashcroft_mueller_statement.html.

- Daschle and D’Orso, Like No Other Time: The 107th Congress and the Two Years That Changed America Forever, 134.

- Jonathan Krim and John Lancaster, “Ashcroft Presents Anti-Terrorism Plan to Congress; Lawmakers Promise Swift Action, Disagree on Extent of Measures,” The Washington Post, September 20, 2001.

- Ibid.

- John Ashcroft, “Attorney General Remarks: Press Briefing” (FBI Headquarters, September 18, 2001), http://www.justice.gov/archive/ag/ speeches/2001/0918pressbriefing.htm; John Ashcroft and Robert Mueller, “Attorney General Ashcroft and FBI Director Mueller Transcript: Media Availability with State and Local Law Enforcement Officials” (DOJ Conference Room, October 4, 2001), http://www.justice.gov/archive/ ag/speeches/2001/agcrisisremarks10_4.htm; John Ashcroft, “Attorney General Ashcroft News Briefing,” October 8, 2001, http://www.justice. gov/archive/ag/speeches/2001/agcrisisremarks10_08.htm.

- Daschle and D’Orso, Like No Other Time: The 107th Congress and the Two Years That Changed America Forever, 135.

- Walter Pincus, “Caution Is Urged on Terrorism Legislation; Measures Reviewed To Protect Liberties,” The Washington Post, September 21, 2001.

- “Transcript of President Bush’s Address,” The Washington Post, September 21, 2001.

- Ellen Nakashima and Rick Weiss, “Biological Attack Concerns Spur Warnings: Restoration of Broken Public Health System Is Best Preparation, Experts Say,” The Washington Post, September 22, 2001; editorial, “Taking Bio-Warfare Seriously,” The Washington Post, September 23, 2001; Justin Blum and Dan Eggen, “Crop-Dusters Thought To Interest Suspects,” The Washington Post, September 24, 2001; Rick Weiss et al, “Suspect May Have Wanted to Buy Plane; Inquiries Reported On Crop-Duster Loan,” The Washington Post, September 25, 2001.

- John Lancaster and Walter Pincus, “Proposed Anti-Terrorism Laws Draw Tough Questions; Lawmakers Express Concerns to Ashcroft, Other Justice Officials About Threat to Civil Liberties,” The Washington Post, September 25, 2001.

- John Lancaster, “Senators Question an Anti-Terrorism Proposal,” The Washington Post, September 26, 2001.

- John Anderson and Vernon Loeb, “Al Qaeda May Have Crude Chemical, Germ Capabilities,” The Washington Post, September 27, 2001; Ceci Connolly, “Bioterrorism Vulnerability Cited; GAO Warns That Health Departments Are Ill-Equipped,” The Washington Post, September 28, 2001; Rick Weiss, “Demand Growing for Anthrax Vaccine: Fear of Bioterrorism Attack Spurs Requests for Controversial Shot,” The Washington Post, September 29, 2001;.

- Sheryl Stolberg, “Some Experts Say U.S. Is Vulnerable To A Germ Attack,” The New York Times, September 30, 2001.

- Dana Milbank, “More Terrorism Likely, U.S. Warns; Bush Wants National Airport Reopened,” The Washington Post, October 1, 2001. The Tommy Thompson quotation is taken from the author’s own collection of ABC News footage (Oct. 1, 2001), which includes Thompson’s CBS performance.

- Ibid.

- Guillemin, American Anthrax: Fear, Crime, and the Investigation of the Nation’s Deadliest Bioterror Attack, 18.

- Weiss, “Demand Growing for Anthrax Vaccine: Fear of Bioterrorism Attack Spurs Requests for Controversial Shot.””

- John Lancaster, “Anti-Terrorism Bill Hits Snag on the Hill; Dispute Between Senate Democrats, White House Threatens Committee Approval,” The Washington Post, October 3, 2001.

- Ibid.

- “History Commons: 2001 Anthrax Attacks,” October 6-9, 2001: Second Wave of Anthrax Attacks Targets Senators Daschle and Leahy.

- John Lancaster, “Hill Is Due To Take Up Anti-Terror Legislation; Bill Prompts Worries Of Threat to Rights,” The Washington Post, October 9, 2001.

- John Bresnahan, “Hill Braces For Anthrax Threat,” Roll Call, October 15, 2001.

- Daschle and D’Orso, Like No Other Time: The 107th Congress and the Two Years That Changed America Forever, 147.

- See, for example, Tish Schwartz, Chief Clerk/Administrator, House Committee on the Judiciary, “Effects of the Anthrax Attacks on the Drafting of the USA PATRIOT Act.” History, Art & Archives, United States House of Representatives https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M51REqSsy9A

- Helen Dewar and Neely Tucker, “Tough Talk, Tears, Confusion and Concern,” The Washington Post, October 18, 2001.

- Colbert I. King, “Don’t Give In to the Anthrax Scare,” The Washington Post, October 27, 2001.

- President Bush Signs Anti-Terrorism Bill (text of Bush Remarks on Oct. 26, 2001 prior to His Signing of the USA PATRIOT Act) (PBS Newshour, October 26, 2001), http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/terrorism/ july dec01/bush_terrorismbill.html?print.

- Helen Dewar and Ellen Nakashima, “Airport Security Bill Still Mired in the Senate,” The Washington Post, October 10, 2001.

- John Lancaster, “Senate Passes Expansion of Electronic Surveillance; Anti-Terrorism Bill Is Set for House Debate Today,” The Washington Post, October 12, 2001.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ellen Nakashima, “US Reasserts Need to Keep Domestic Surveillance Secret,” Washington Post, December 21, 2013.

- “Timeline of NSA Domestic Spying,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, accessed May 23, 2014, https://www.eff.org/nsa-spying/timeline.

- Ibid.

- Natasha Lennard, “Clapper: We Should Have Told You We Were Spying on You,” Salon, February 18, 2014, http://www.salon.com/2014/02/18/ clapper_we_should_have_told_you_we_were_spying_on_you/.