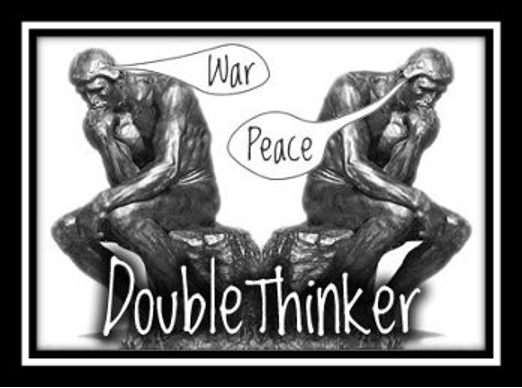

We shall begin this section on the lighter side with George Orwell’s brilliant concept of “doublethink,” coined in his dystopian novel, 1984.1

In 1984’s not-so-fictional world, doublethink is a word in the Newspeak lexicon. Newspeak, which replaces Oldspeak’s “reality control,” is a new, politically correct language consisting of a meager vocabulary that has been developed by the powers that be (the High) for the purposes of controlling the public’s worldview and limiting the possibility of independent thought. In other words, by controlling the words permitted to exist in the language, the High are able to control the thoughts people are allowed to have.

In addition to limiting vocabulary, the High require another thought-control method: doublethink. Citizens must learn the hypnotic skill of consciously inducing unconsciousness. This practice enables them to hold two conflicting beliefs at the same time and to call upon each belief as needed, depending on the situation. In so doing, citizens become adept at readily conforming to the vicissitudes of the official platforms of the day.

The reason the High insist on everyone being grounded in doublethink is that, if they are to retain power over the people permanently, the prevailing mental condition in the land must be that of insanity. So citizens must use this subtle process of thought control on themselves in order to stay out of touch with reality. Paradoxically, they learn to embrace insanity in order to stay sane.

Though the term doublethink is not included in today’s official psychological vocabulary, perhaps it should be, given that it’s such a common defense mechanism. Regardless, the concept of doublethink has established itself in our culture, since it aptly — even humorously — describes the capacity of the human mind to readily adapt to any official pronouncement on any subject, such as 9/11, while at the same time being fully aware of evidence that contradicts those official pronouncements!

In fact, because doublethink is such a sophisticated form of spontaneous, situational self-censorship, the capacity to employ it is quite a mental feat.

By the way, doublethink is precisely the same as Orwell’s “blackwhite,” which is the ability to brazenly claim that black is white, or vice versa, in bold-faced contradiction to irrefutable evidence.

Here are a couple of textbook examples of doublethink.

Exasperated with a friend, I declared, “I know you believe that 9/11 was a false flag operation and that we are in the Middle East for natural resources, but you keep speaking of ‘the War on Terror’ as though it’s the real reason we have invaded Afghanistan and Iraq and the real reason we now use drones to kill so-called terrorists. Why do you do this?!”

She shot back testily, “Well, we are surrounded by the official story. It’s everywhere — the TV, the newspapers, our teachers and friends at school, at work. What am I to do?!”

Doublethink was her survival strategy — a paradoxical embrace of insanity to stay sane.

A while later, I had a similar exchange with a friend who had included in her recent book some words corroborating the official 9/11 myth, which I knew she didn’t believe. Frustrated, I confronted her: “Why do you use those words? I know you don’t believe them.”

With obvious irritation, she replied, “Look, I know we were lied to. But my work in the world is very important to me, and if I am to continue it, I can’t have my taxes audited!”

My friend was so fearful of retaliation from corrupt authorities that she had adopted the defense of holding both worldviews in mind, vacillating automatically between them as the occasion demanded. Classic doublethink. Thank you, George Orwell!

As these two illustrations make clear, doublethink is the defensive strategy of holding two contradictory beliefs in mind at the same time and switching back and forth between them — rather like a chameleon changing his colors — as circumstances demand.

An alternative defense strategy, which I will explore in the next segment, is the use of denial for the purpose of avoiding cognitive dissonance.

Copyright © Frances T. Shure, 2014

Part 5: Denial and Cognitive Dissonance >

Endnotes

- George Orwell, 1984 (Harcourt Brace and Company, 1949).

Jackie Jura, “Today’s Orwell,” http://www.orwelltoday.com.

Note: Electronic sources in the endnotes have been archived. If they can no longer be found by a search on the Internet, readers desiring a copy may contact Frances Shure using this email address: franshure [at] estreet.com

You must replace the “[at]” in the email address above with the “@” symbol and remove the spaces for it to be a valid email address. The address above is listed as such to prevent spam from being sent to this email address.