On September 21, 2001, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) referred specific transactions to the FBI for criminal investigation as potential insider trades related to 9/11. One of those trades was a September 6, 2001 purchase of 56,000 shares of a company called Stratesec, which was a security contractor for several of the facilities that were compromised on 9/11. Those facilities included the WTC complex, Dulles Airport, where American Airlines Flight 77 took off, and also United Airlines, which owned two of the other three ill-fated planes.

The Stratesec stock was purchased by a director of the company, Wirt D. Walker III, and his wife Sally Walker.[1] This is clear from the memorandum generated to record the FBI summary of the suspicious trades.[2] The Stratesec stock that the Walkers purchased doubled in value in the one trading day between September 11th and when the stock market reopened on September 17th. Unfortunately, the FBI did not interview either of the Walkers and they were both cleared of any wrongdoing because they were assumed to have “no ties to terrorism or other negative information.”[3]

However, Wirt Walker was connected to people who had connections to al Qaeda. For example, Stratesec director James Abrahamson was the business partner of Mansoor Ijaz, a Pakistani businessman who claimed on several occasions to be able to contact Osama bin Laden.[4] Additionally, Walker hired a number of Stratesec employees away from a subsidiary of The Carlyle Group called BDM International, which ran secret (black) projects for government agencies. The Carlyle Group was partly financed by members of the Bin Laden family.[5]

The insider trading evidence indicates that Wirt Walker could be brought up on charges today, for crimes related to 9/11. But there are many other reasons why Walker should be investigated. The work that Stratesec did at the WTC and at the other 9/11-impacted facilities is of considerable interest and, although only briefly covered in this chapter, those activities will be examined more closely in the next. One thing that will be important to consider is that Stratesec’s role in managing the security systems for the WTC and Dulles Airport suggests that the company could have had backdoor access to those systems.

Apart from the access and the insider trading suspicions, reasons to investigate Walker include the following.

- From the early 1980s, Walker ran what would be Stratesec’s parent company, the Kuwait-American Corporation (KuwAm), which was linked through its directors to the terrorist financing network BCCI.

- Walker’s activities with regard to Kuwait ran parallel to those of two men who were known to be CIA operatives.

- KuwAm had a number of subsidiaries that went bankrupt shortly after 9/11 and there are reasons to believe that some of those subsidiaries, including Stratesec, were fronts for covert operations.

- Walker was always able to maintain strong cash flow despite dismal business performance.

- After 9/11, the people who had become Stratesec’s majority stockholders were convicted of conspiracy.

- And several of Walker’s companies were located in the same offices that were later occupied by Zacarias Moussaoui’s flight trainer.

It is informative to begin a review of Walker’s possible role with an examination of his history, as well as the background of Stratesec and KuwAm.

The History of Wirt Walker

Wirt Walker, CEO of Stratesec and managing director at KuwAm, was the son of a career U.S. intelligence officer who had worked for both the CIA and, later, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA).[6] Walker was also a descendant of James Monroe Walker, who ran the businesses of the U.S. deep state organization called Russell & Company that had used profits from the Opium Wars to purchase much of the infrastructure of the United States.[7] Coincidentally, the son-in-law of James Monroe Walker, John Wellborn Root, was the first employer and guardian of Emery Roth, whose company was the architect of record for both the WTC towers and building 7.[8]

Today Wirt Walker lives in McLean, Virginia, home of the CIA. He graduated from Lafayette College in 1968 and in 1971 he married Sally Gregg White, a Washington DC debutante. Sally is a descendant of architectural ironwork magnate George White, whose son “Doc” White was a World Series winning pitcher for the Chicago White Sox. “Doc” was actually a dentist but his brother, Charles Stanley White, was a famous Washington DC surgeon and grandfather to Sally. Charles Stanley White Jr., Sally’s father, was a surgeon too and, like Walker’s father, he was an officer in the Army Air Corps during World War II.[9]

Walker was fortunate to land a position, right out of college, as a broker for an investment firm called Glore Forgan.[10] Originally a company called Field Glore, financed by Marshall Field III; Glore Forgan was renamed in 1937 for its new partner, James “Russ” Forgan. Russ was one of the most influential men in the history of U.S. intelligence, having led the European division of the CIA’s predecessor organization, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).[11] In the OSS, Forgan focused on infiltrating the German intelligence apparatus with the help of William Casey. Before going back to work in the investment business, Forgan helped to write the documents that created the CIA. Later chairman of the SEC under Nixon, Casey was to become the long-term director of the CIA under Reagan.

While Walker worked there, William Casey was house counsel for Glore Forgan. It was at this time that the firm was at the center of a near collapse of Wall Street. In 1970, it began to be clear that Glore Forgan had somehow sold many millions of dollars more in securities than what were actually available to sell. As a result, the company was expected to fail and, due to a cascading effect, its failure was projected to take down dozens of other firms causing a panic and huge losses on Wall Street.[12] These projections compelled President Nixon to ask Ross Perot, through Treasury Secretary John Connally, to intervene and save Glore Forgan. Perot suffered dramatic losses in an attempt to save the company (the only business loss of his career) and Glore Forgan went bankrupt anyway. The U.S. government created the Securities Investor Protection Corporation in response.[13]

Walker left Glore Forgan to become a young vice president at the investment firm of Johnston & Lemon in Washington, DC. As of 1980, he worked in the corporate finance department at Johnston & Lemon with several others including Stephen Hartwell, a fellow alumnus of Lafayette College.[14] Hartwell went on to become an advisor at First American Bank of Virginia, a subsidiary of the BCCI-owned First American Bank.

Shortly thereafter, Walker went from being an investment broker to running an assortment of small companies that tended to go bankrupt. Yet somehow, he always had funding. That could have been due to the fact that Walker was a close associate of members of the Kuwaiti royal family and, by 1982, he was a director of KuwAm.

KuwAm owned a company called Aviation General, for which Walker was CEO, and like Stratesec this company and its subsidiaries went broke shortly after 9/11. Furthermore, a company called Hanifen Imhoff was the underwriter for one of those subsidiaries.[15] A division of a company led by George W. Bush’s first cousin, George Herbert Walker III, Hanifen Imhoff was “nailed for Correspondent’s fraud” in December 2000.[16]

Stratesec and the KuwAm Corporation

Twenty-one year old Mish’al Yusuf Saud Al-Sabah, the majority owner of KuwAm Corporation, became the company’s first chairman in 1982. Wirt Walker was named managing director. The two men already had a close history, because Al-Sabah had actually lived with Walker and his family for six months in 1976, when Al-Sabah was only 15 years of age.[17] That was when George H.W. Bush was CIA director and Ted Shackley was one of his assistant directors.

As a great-grandson of Kuwaiti’s historic ruler Muhammad I, Mish’al Al-Sabah is very well connected to the Kuwaiti royal family and, therefore, to the Kuwaiti government. Through his relations, Al-Sabah brought Walker and KuwAm “many rich, limited partnership investors from Kuwait, Europe and the U.S.”[18] And Walker brought the Kuwaiti royal family into a position of implementing security systems for facilities that were central to the events of 9/11.

A November 1990 article in The Boston Globe reported that Mish’al was not the only member of the Kuwaiti royal family that was a director at KuwAm. Also on the board was a partner in a prominent U.S. law and lobbying firm.

“A Securities and Exchange Commission filing shows another member of the Al-Sabah family on the KuwAm board, alongside a partner of the politically well-connected Washington law firm of Patton, Boggs & Blow. According to the Dow Jones News Retrieval Service, tiny KuwAm (estimated assets: $20 million) also owns significant portions of Los Angeles-based videocassette distributor Prism Entertainment Corp., where Walker sits on the board, and a Sunnyvale, Calif.-based light-sensor equipment distributor called ILC Technology Inc., where Walker is chairman of the board.”

The first Gulf War was started on the basis of blatant lies, at least one of which involved a relative of Mish’al Al-Sabah. This was a 15-year old girl named Nayirah, who was the daughter of Mish’al’s first cousin, Saud Nasser Al-Saud Al-Sabah, the Kuwaiti ambassador to the United States.[19] The girl lied about having witnessed Iraqi soldiers taking babies out of incubators and leaving them on the “cold floor to die.” It was later learned that she had been coached to tell the lies by the public relations firm Hill & Knowlton.[20]

Hill & Knowlton chairman Robert Gray had previously been a director of First American Bank, BCCI’s Washington subsidiary, along with Dick Cheney’s Halliburton colleague Charles DiBona. Gray had been on the Reagan-Bush election team and was known for being open about his companies doing work for the CIA. A good review of the Nayirah story that covers Gray and his close relationship with William Casey can be found in Susan Trento’s book The Power House.[21]

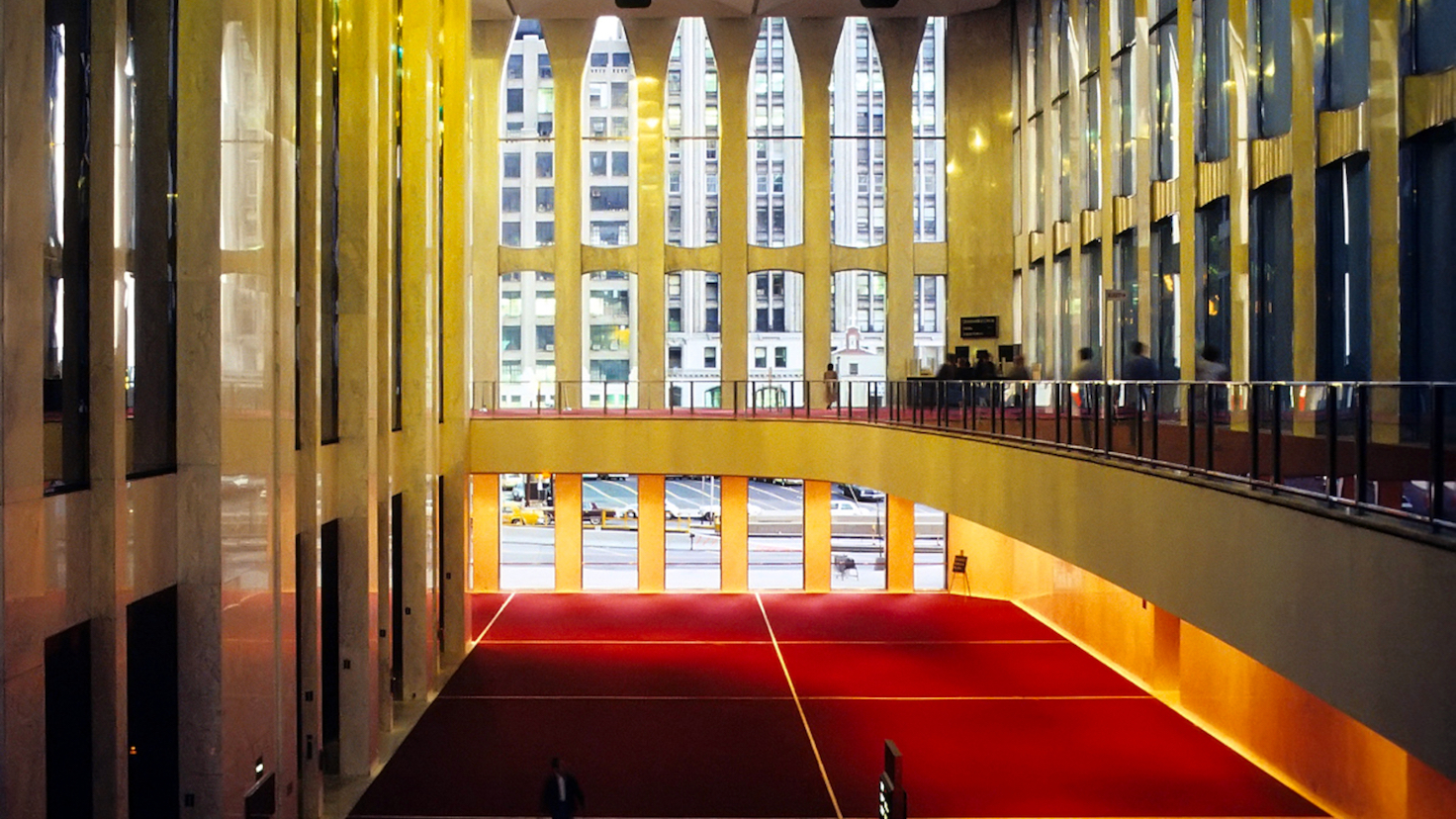

Stratesec started off in 1987 as Burns & Roe Securacom, founded by Sebastian Cassetta, an assistant to Nelson Rockefeller. During the first Bush presidency, in 1991, Securacom (from here on called Stratesec) was hired by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to provide a review of security risks at the WTC. Stratesec’s report warned of “international activities” arising from recent “Mideast events,” hinting at the possibility of Arab terrorism at the WTC. The report called for the adoption of “a master plan approach to the development of security systems.”[22]

KuwAm took over Stratesec the next year, in 1992, at which time Walker became CEO. Walker was among the new shareholders of Stratesec and, along with Al-Sabah, he joined the Stratesec board. Throughout the next decade, Stratesec stock would be held by shell companies, controlled by Walker and Al-Sabah, called Fifth Floor Company for General Trading and Contracting, and Special Situation Investment Holdings.

When Walker was sued by the president of an existing company with an identical name (Securacom at the time), Wirt became abusive and told the other businessman that he “would bury him financially and take everything he had” by “filing a barrage of frivolous arguments in multiple jurisdictions.”[23] Walker lost the case and had to change his company’s name to Stratesec. While this incident suggested that Walker was abusive, it also indicated that he had the kind of deep pockets that allowed for frivolous lawsuits.

Marvin Bush, son of George H.W. Bush, joined the board of Stratesec after meeting members of the royal family of Kuwait on a trip to that country with his father in April 1993. During that trip, the Kuwaiti royals displayed enormous gratitude to the elder Bush for having saved their country from Saddam Hussein only two years earlier.

But the Bush-Kuwaiti connection went back much farther, to 1959, when the Kuwaitis helped to fund Bush’s start-up company, Zapata Off-Shore.[24] As a CIA business asset during this time, Bush and his company worked directly with anti-Castro Cuban groups in Miami before and after the Bay of Pigs invasion.[25]

During the 1993 trip, the royals in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) showed similar gratitude to the Bush family by putting Marvin on the board at Fresh Del Monte, which was purchased by the UAE-owned company IAT in 1994. The alleged 9/11 hijackers had many connections to the UAE, and much of the funding for the attacks came through that country.

As mentioned in the chapter on Richard Clarke, the Joint Congressional Inquiry into 9/11 stated that the UAE was one of three countries where the operational planning for 9/11 took place. For some reason, although the Joint Inquiry went into detail on the other two countries, it seemed to make a point of avoiding further comment about the role of the UAE.[26] The UAE was also behind the creation of BCCI and, after the alleged dissolution of that terrorist network, had purchased its assets entirely.

In 1996, Al-Sabah announced that KuwAm’s subsidiary Aviation General was selling aircraft to the National Civil Aviation Training Organization (NCATO) in Giza, Egypt.[27] NCATO was in a partnership with Embry-Riddle University where two of the alleged 9/11 hijackers, Saeed Alghamdi and Waleed Al-Shehri, were said to have gone to flight school.[28] Ten days after the attacks, Embry-Riddle was relieved by reports that Al-Shehri was alive.[29] Unfortunately, the reports that some of the alleged hijackers had turned up alive were never investigated by the FBI or the 9/11 Commission.[30]

Like Stratesec, all three of KuwAm’s aircraft companies went bankrupt within three years after 9/11. The company blamed terrorism and the war in Iraq for a reduced demand for its products.[31] Despite the losses, the Kuwaiti royal family can be said to have benefited from 9/11 due to the War on Terror that removed Saddam Hussein from power. Of course, that was the second consecutive U.S. war that Kuwait benefited from, the first being the 1991 Gulf War led by President George H.W. Bush.

Other KuwAm Directors and Investors

As stated before, The Boston Globe reported that KuwAm’s directors included a partner of the law firm Patton, Boggs & Blow.[32] This is the firm that took over representation of BCCI after Clark Clifford’s demise in the late 1980s. Patton Boggs & Blow also represented BCCI’s owners – the royal family of the United Arab Emirates.

KuwAm had other principals and partners over the years, including Pamela S. Singleton, who was associated with Winston Partners, another company run by Marvin Bush. Richard J. Cordsen was another director of KuwAm and its subsidiary Commander Aircraft. Cordsen was primarily associated with United Gulf Group, a Saudi Arabian company. However, it was KuwAm director Robert D. van Roijen who was said to be the man responsible for getting Walker involved in the aircraft business.

Like Walker, van Roijen was the son of a CIA officer. His father was born a Dutch citizen in England, had immigrated to the U.S. in the 1930s, and was an intelligence officer in the Army Air Corps, just like Walker’s father was before he joined the CIA. The senior van Roijen later became the owner of Robert B. Luce, Inc., a Washington-based company that published The New Republic.

Van Roijen’s grandfather was the Dutch ambassador to the United States in the 1920s, and his uncle, Jan H. van Roijen, had the same appointment from 1950 to 1964. Uncle Jan was also a member of the Bilderberg Group. During the 1973 Oil Crisis (when Rumsfeld was at NATO headquarters), the Dutch government sent Jan H. van Roijen to Saudi Arabia in an unsuccessful attempt to patch things up diplomatically.

Unlike Walker, KuwAm’s van Roijen admits that he was an intelligence officer too, with the U.S. Marines from 1961 to 1963. It is interesting to note that the CIA-trained anti-Castro Cubans that Marvin Bush’s father was helping, during this same time, thought that the U.S. Marines would be right behind them as they stormed the shores at the Bay of Pigs.

KuwAm’s Van Roijen had once been Tricia Nixon’s White House party escort during the Nixon Administration. Van Roijen’s sister was working in the White House communications office, and he used those connections to his advantage as a lobbyist for IBM, obtaining strategic information from government offices such as the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB).[33] At the time, future Carlyle Group CEO Frank Carlucci was Deputy Director of the OMB.

Another interesting connection between KuwAm, the Nixon years, and Saudi Arabia was that KuwAm’s offices were in the Watergate Hotel, the same building that was burglarized in the 1972 scandal that led to Nixon’s resignation. In the years leading up to 9/11, both Stratesec and Aviation General convened their annual shareholders’ meetings in KuwAm’s Watergate office, in Suite 900.[34] As of 1998, the building was owned by The Blackstone Group and the offices that KuwAm occupied were leased by the Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia which occupied the suite just below KuwAm. The Kuwait embassy also had offices in the building.

The directors and shareholders of Stratesec formed a notable group, as will be discussed in the next chapter. Even more interesting are the links between KuwAm and BCCI.

Were Walker and KuwAm Working for an Intelligence Network?

There are a number of reasons to suspect that Wirt Walker and the KuwAm Corporation were working either for the CIA or for a private intelligence network. These reasons include that Walker became close to the Kuwaiti royals at the same time as they were working closely with two other Americans who were involved in deep state operations. Moreover, the people pulling the strings from the Kuwaiti side in these endeavors were close relatives of KuwAm chairman Mish’al Al-Sabah.

The first of the two deep state operatives was the famous CIA man who led the private network, Ted Shackley. Having worked in the CIA for decades, Shackley was the agency’s Associate Deputy Director of Operations from 1976 to 1977. He was described by former CIA director Richard Helms as “a quadruple threat – Drugs, Arms, Money and Murder.”[35] Walker has a number of things in common with Shackley. In the 1980s, both men were strongly linked to the Bush family network, to Kuwait, and to aviation. They both ran security companies as well.

As stated in Chapter 3, Shackley was a close friend of Frank Carlucci. While Carlucci was functioning as an operative in the “foreign service” and then the Nixon Administration, Shackley was leading many CIA operations around the world including the anti-Castro plan Operation Mongoose, the secret U.S. war in Laos, and the overthrow of Salvadore Allende in Chile.

After leaving the CIA in 1979, Shackley formed his own company, TGS Associates, which appeared to be focused on obtaining access to places like Kuwait and Iran. TGS functioned as a broker for Boeing 747 aircraft, attempted to sell food and medical supplies to Iran, and did construction work in Kuwait.

At the same time, Shackley took part in the Reagan campaign operation which resulted in the American hostages in Iran being held until Reagan was inaugurated in 1981. Over a period of years following this, Shackley and some of his former CIA friends, Thomas Clines and Richard Secord, became involved in the Iran-Contra affair.[36]

When Walker’s KuwAm was just getting off the ground, Shackley was beginning to secure contracts with the Kuwaiti government. George H.W. Bush had helped Shackley get started in Kuwait around that time. Bush’s contacts there went back to the days when Kuwait and other oil-rich royals in the region helped fund his Zapata Off-Shore operation.[37]

In his biography of the man, author David Corn wrote that “Shackley viewed Kuwait as a tremendous source of profits.” Those profits appeared to be tied to the Kuwaiti royal family’s interests. In 1982, the year that KuwAm was incorporated in Washington, the Kuwaiti government specifically requested that the U.S. Navy award Shackley’s firm a $1.2 million contract to rehabilitate a warehouse for the Kuwaiti Air Force, although Shackley had “little experience in this area.”[38]

By the end of 1983,”TGS had before the Kuwaiti Air Force several proposals that could bring it up to $200 million. What Shackley received was more modest, but nevertheless much money. Toward the end of 1983, TGS International signed a $6.3 million deal with the Navy to perform construction at the Ali Al-Salem Air Base, forty miles outside of Kuwait City.”[39]

But TGS did not serve the Navy well, falling behind schedule and failing to complete the contract. The result was a lawsuit between TGS and its sub-contractor, RJS Construction, and another between TGS and the U.S. government. TGS prevailed in the latter, claiming that its suppliers and employees could not function well in a war environment (the Iran-Iraq War was ongoing). Several of TGS’ shareholders were Iranian exiles, including former SAVAK agent Novzar Razmara.[40]

TGS was also involved in dealings on the other side of the world. In October 1984, when Congress had cut off funding to the Contras, John Ellis Bush (brother of Stratesec director Marvin Bush) put the Guatemalan politician Dr. Mario Castejon in touch with Oliver North. This led to Castejon proposing that the U.S. State Department supply miscellaneous, ostensibly non-military assistance to the Contras. The proposal was passed to the CIA through TGS International, the firm owned by Shackley.[41]

Shackley continued working in Kuwait by way of another of his ventures called Research Associates International (RAI), which specialized in “risk analysis” by providing intelligence to business interests. Shackley also testified that RAI was a security company. “We design security systems,” he said, confirming yet another similarity between his business activities and those of Walker.[42]

RAI’s primary customer was Trans-World Oil, run by a Dutch citizen named John Deuss. The work involved smuggling oil into South Africa in violation of an embargo.[43]

Another CIA operative was working with the Kuwaiti royals at the same time as Walker and Shackley. In the case of Robert M. Sensi, CIA connections to the Kuwaiti royal family, at the same time that Walker became a close colleague of Mish’al Al-Sabah, were confirmed. While working for the Washington office of Kuwait Airways, which was owned by the Kuwaiti government, Sensi operated covertly as a CIA asset. He organized the 1980 flights for William Casey to Europe for meetings on the deal to hold the hostages. In the mid-1980s, he helped set up CIA fronts in Iran along with Iranian exile Habib Moallem.

Sensi’s work for the Kuwaitis and the CIA came to light in a late 1980s series of articles in the Washington Post that covered legal proceedings in which Sensi had been accused of embezzling funds from Kuwait Airways. During the proceedings, the CIA admitted that Sensi had worked for the agency for years and Sensi’s supervisor at the company, Inder Sehti, admitted that Sensi had been allowed by the Kuwaiti government to use a slush fund for CIA purposes.[44] Apparently, these purposes included managing the U.S. visits of Kuwaiti royal family members. Presumably, this would have included the travel arrangements for young Mish’al Al-Sabah when he came to live with Walker’s family.

Sensi claimed that he was nominally working for Kuwait Airways and the Kuwaiti royal family was funding his activities. He also claimed to be acting under the direction of the Kuwait ambassador to the United States.[45] When Sensi signed on to the job, in 1977, the Kuwait ambassador to the U.S. was Khalid Muhammad Jaffar. In January 1981, while Sensi was still using the Kuwaiti funds for CIA work, Jaffar was succeeded by Nayirah’s father, the first cousin of KuwAm’s Mish’al Al-Sabah.

Sensi also clarified that, as a CIA asset, he was “being run directly by CIA director William Casey, in close concert with Vice President Bush.”[46] This is yet another interesting connection between Walker and Sensi, in that Walker worked with Casey at Glore Forgan a decade earlier and with Bush’s son at Stratesec.

The Kuwaiti royal who approved the use of this CIA slush fund for Sensi was Jabir Adbhi Al-Sabah, the vice chairman of Kuwaiti Airways and Kuwait’s chief of civil aviation.[47] Like Nayirah, Jabir Adbhi Al-Sabah was closely related to KuwAm’s Mish’al Al-Sabah, as a first cousin once removed. What’s more, Jabir’s colleague, the chairman of Kuwaiti Airways, was none other than Faisal al-Fulaij, BCCI’s nominee from Kuwait. Al-Fulaij was deeply involved in the operations of BCCI and its U.S. subsidiaries.[48]

The U.S. Senate investigation into BCCI, led by John Kerry, stated that “Some funds were borrowed by one ‘investor,’ Fulaij, from the Kuwait International Finance Company (“KIFCO”), which BCCI purportedly had a 49 percent interest in, but actually owned and controlled through its nominee, Faisal al-Fulaij.” The man who was both Finance and Oil minister in Kuwait was Abdul Rahman Al-Atiqi, a major investor in BCCI and later a director of a related company called InvestCorp.

This BCCI connection leads to a discussion of Hamzah M. Behbehani, who was a director and partner at KuwAm from 1995 to 1997, and was named as a principal, along with Walker and Al-Sabah, in lawsuits in which KuwAm engaged. Behbehani had come to KuwAm after spending three years with investment companies in London. Prior to that, from 1986 to 1992, Behbehani had worked for the British branch of the Banque Arabe et Internationale d’Investissments (BAII), one of the Arab-Western partnership banks started in the 1970s.

BAII was “heavily involved in the oil trade” and it financed “oil imports and the export of capital goods and equipment for the refining and petrochemical industries.”[49] But as authors Peter Truell and Larry Gurwin noted, BAII was also intimately associated with the CIA-linked network BCCI.

“Run by a board member of BCCI, Yves Lamarche, BAII had played a critical role in some of BCCI’s dubious schemes, lending $50 million to help finance the takeover of First American and also providing funds to allow [Ghaith] Pharaon to buy Independence Bank in Los Angeles.”[50] KuwAm director Behbehani worked for BCCI’s partner BAII from the time Pharaon purchased Independence Bank and throughout the time that the financial crimes, in which these banks engaged, were revealed.

BCCI was known for funding terrorism and was also closely linked to Pakistan’s ISI. These facts, and the UAE links to al Qaeda, have led many to suspect that BCCI was behind al Qaeda. The connections between the KuwAm Corporation and BCCI are therefore of great interest given Stratesec’s security contracts at the facilities that were affected by the 9/11 attacks.

In 2005, a different Mish’al Al-Sabah, who was another first cousin of KuwAm’s Mish’al, provided yet more evidence that Kuwait had al Qaeda ties. This Al-Sabah was brought to trial in Kuwait for certain inflammatory claims he had made. Mish’al Al-Jarrah Al-Sabah, Kuwait’s Assistant Undersecretary for State Security Affairs at the time of the 9/11 attacks, made these claims in an interview on a U.S.-funded Kuwaiti television program called Al Hurra. Al-Sabah was charged with claiming that “that there is an old base for the al-Qaeda organization in Kuwait.” He also accused two Kuwaiti government MPs “of belonging to al-Qaeda.” During a five and a half hour closed-door inquisition, he recanted the claims.[51] Despite this retraction, other evidence exists that links KuwAm and al Qaeda.

Wiley Post Airport

KuwAm’s Aviation General was the parent of two wholly-owned subsidiaries: Commander Aircraft Company, which manufactured Commander-brand aircraft, and Strategic Jet Services, which provided aircraft brokerage and refurbishment services. Aviation General, Commander Aircraft, and Strategic Jet Services were all located in Hangar 8 of Wiley Post Airport in Bethany, OK, near Oklahoma City.

In another apparent coincidence, CIA asset Robert Sensi had listed an Oklahoma City address as his residence for a period of time.[52] The address Sensi gave was for the Oklahoma City Halfway House, a drug and alcohol rehabilitation center located 11 miles from Wiley Post Airport.

As reviewed in Chapter 5, a motel not far from Wiley Post was frequented by alleged 9/11 pilots Mohamed Atta and Marwan Al-Shehhi, and their alleged accomplice Zacarias Moussaoui. Curiously, just a few years before, convicted OKC bombers Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols stayed at the same motel, “interacting with a group of Iraqis during the weeks before the bombing.”[53] Louis Freeh’s FBI didn’t seem to want this information even though it was repeatedly provided by the motel owner. In August 2001, the motel owner testified that he saw Moussaoui, Atta, and Al-Shehhi at his motel when they came late one night to ask for a room.

Between February and August of 2001, Moussaoui lived twenty miles away in Norman where he attended a flight school run by David Boren’s university. According to Moussaoui’s indictment, Atta and Al-Shehhi had visited the same flight school in July 2000, but did not take classes there.

FBI summary documents prepared for the 9/11 investigations state that Mohamed Atta was also spotted at Wiley Post Airport within six months of the 9/11 attacks. Atta was witnessed flying at Wiley Post along with two other alleged 9/11 hijackers, Marwan Al-Shehhi and Waleed Al-Shehri.[54] Other FBI summary documents indicate that Saeed Al-Ghamdi was also seen flying in to Wiley Post Airport on an unspecified date and that Hani Hanjour had made inquiries to a flight school there.[55]

Therefore it is a remarkable fact that Wirt Walker and his companies were located at this same airport. But the surprises don’t stop there. Wiley Post has approximately 24 hangars and Hangar 8 is set off away from the rest.[56] Although Aviation General and its subsidiaries all went bankrupt or were sold off in the few years after 9/11, Hangar 8 still houses three businesses. These are Jim Clark & Associates, Valair Aviation, and Oklahoma Aviation.

At first glance, the most interesting of these new Hangar 8 companies is the flight school called Oklahoma Aviation. This is due to an incredible coincidence regarding the young man who heads the company, Shohaib Nazir Kassam.

In March 2006, Kassam was a government witness against Zacarias Moussaoui. He was, in fact, Moussaoui’s flight instructor. To emphasize, the guy who now occupies Wirt Walker’s offices in Hangar 8 at Wiley Post Airport not only knew Zacarias Moussaoui, he was Moussaoui’s primary flight instructor at Airman Flight School in Norman, OK.

Kassam moved to Norman in 1998, at the age of 18, coming from Mombassa, Kenya. He was originally from Pakistan. Two years after he arrived in Norman, he completed his training to become a flight instructor. He was only 21 years of age when he spent 57 hours (unsuccessfully) trying to train Zacarias Moussaoui to fly.

Oklahoma Aviation was a flight school that was just getting off the ground in 2005. Yet as it took over Hangar 8 from Aviation General, shortly after the company formed, it soon boasted of having the best planes around. This was the opposite of the apparent financial fortunes of the Aviation General companies that all went belly up that year. And it was also unlike Airman Flight School which, although it was in the same area and same business as Oklahoma Aviation, shut down in 2005 because it could not pay the rent.

It seems there is more to the story of KuwAm’s aviation companies, and those related to Hangar 8. If nothing else, an investigation must consider that it is not simply a coincidence that Zacarias Moussaoui’s primary trainer is now occupying the offices of Wirt Walker’s former businesses at Wiley Post Airport. And although the three KuwAm companies operated out of Wiley Post, they were all officially headquartered at the famous Watergate Hotel in Washington DC, in office space leased by the Saudi and Kuwaiti governments.

In the few years leading up to this change in tenancy at Wiley Post Airport, other interesting things were happening with KuwAm’s aviation companies. In September 2000, John DeHavilland of British Aerocraft joined as CEO of Strategic Jet Services. Three months later, and on the same day that a young man named Kamran Hashemi joined Stratesec, Walker’s president at Commander Aircraft, Dean N. Thomas, died suddenly at a young age.[57]

Aviation General continued to be, like Stratesec and the other companies that Wirt Walker ran, a rare example of well-financed business failure. As of 1998, Aviation General was losing millions of dollars every year. The year 2000 performance was the best in the company’s history, according to Walker, although it represented only humble positive returns. But by August 2001, the company was reporting million-dollar losses again and it began to miss lease payments at Wiley Post Airport. Despite the problems, Walker said the company would survive because “we’ve got pretty deep pockets.”[58]

In late 2002, Strategic Jet Services “discontinued its operations and began the process of dissolving the company.”[59] Commander Aircraft filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy at the same time and that status was changed to Chapter 7 in January 2005. Commander Aircraft left Oklahoma in September 2005 to move to an “undisclosed location.” And Aviation General was sold to Tiger Aircraft, a small company with Taiwanese investors that went bankrupt in 2006.

Incredibly, after 9/11 Walker showed up the next time an airplane crashed into a tall building. The first such occurrence after the attacks, in an incident in Italy, led to Walker being interviewed because the plane that crashed was related to his company, Aviation General.[60]

Walker Says He Just Owned Some Stock

After the 9/11 attacks, Walker was interviewed by phone about his company’s work at the WTC. When asked whether FBI or other agents had questioned him or others at Stratesec or KuwAm about the security work the company did related to 9/11, Walker declined to comment. Disclaiming any responsibility, he simply said, “I’m an investment banker. We just owned some stock.” Walker went on to say that his investment company (KuwAm) “was not involved in any way in the work or day-to-day operations” of the security company.

Of course, these answers were diversionary and untrue because Walker had served as Stratesec’s CEO. Furthermore, his activities with regard to Kuwait ran parallel to those of two known CIA operatives, and Walker would soon thereafter be suspected of engaging in insider trading related to 9/11.

KuwAm was owned by people who stood to gain much from the response to 9/11. This was highlighted by the fact that KuwAm held its meetings in space leased by the Saudi Arabian and Kuwaiti embassies. Marvin Bush was reelected to his annual board position in Saudi and Kuwaiti-leased meeting rooms at the Watergate.

Additionally, the CIA-linked Riggs Bank, for which Marvin’s uncle was a board member, also had a large office at the Watergate. Saudi Princess Haifa bint Faisal, the wife of Prince Bandar, used her checking account at Riggs to send money to Omar Al-Bayoumi, the man who first sponsored Al-Mihdhar and Al-Hazmi in San Diego. Other Saudi accounts at Riggs were also linked by investigators to some of the 9/11 hijackers.[61]

In September 2003, both Hamzah Behbehani and Mish’al Al-Sabah had U.S. warrants issued for their arrest for contempt of court (failure to appear). This was a result of a lawsuit involving KuwAm’s subsidiary Advanced Laser Graphics.[62]

By this time, KuwAm had already divested from Stratesec and Walker had turned to financing from another dubious operation. A company called ES Bankest became Stratesec’s majority shareholder, owning about 47% of the company’s stock. According to SEC documents, Stratesec reached a “verbal agreement” with the financier in October 2000 in which accounts receivable were sold at a discounted price to provide cash flow.[63] Walker transferred millions of dollars in shares of Stratesec stock to ES Bankest as a way to reduce debt.[64]

By the time Stratesec “abruptly shut its doors,” in September 2003, it had become entirely dependent on ES Bankest.[65] The owners of ES Bankest, brothers Eduardo and Hector Orlansky, were convicted only months later of conspiracy and bank fraud when $185 million went missing due to “huge overadvances.”[66] Apparently, $2 billion was “flowed through the Orlansky’s two businesses from 1998 to 2003 to create the appearance they were healthy and growing.”[67]

Walker now runs his own private investment company called Eigerhawk, and he is a director at Vortex Asset Assessment. He also works with Arthur Barchenko at Electronic Control Security. Barchenko was a member of several committees addressing FAA regulations related to “access control and perimeter intrusion devices” and was a member of the special access control security task force for the FAA.

To reiterate some of the reasons that Walker should be investigated for 9/11:

- From the early 1980s, Walker managed KuwAm, which was linked through its directors to the terrorist financing network BCCI.

- KuwAm’s subsidiaries went bankrupt shortly after 9/11 and there are reasons to believe that some of those subsidiaries, including Stratesec, were fronts for covert operations.

- Through its security contracts, Stratesec had unparalleled access to several of the facilities which were central to the events of 9/11.

- Stratesec held its company meetings in space leased by the governments of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, both of which benefited from the response to 9/11.

- Walker’s activities with regard to Kuwait ran parallel to those of two men who were known to be CIA operatives.

- Shortly after 9/11, Stratesec’s primary stockholders were convicted of conspiracy.

- A stock purchase made by Walker and his wife, the week of 9/11, was flagged by the SEC as possible 9/11 insider trading.

- And several of Walker’s companies were located in the same offices that were later occupied by Zacarias Moussaoui’s flight trainer.

The next chapter, focused on Stratesec’s chief operating officer, will give more detail on the company’s 9/11-related contracts and opportunities.

Notes to Chapter 12

- Kevin R. Ryan, Evidence for Informed Trading on the Attacks of September 11, Foreign Policy Journal, November 18, 2010

- 9/11 Commission memorandum entitled “FBI Briefing on Trading”, prepared by Doug Greenburg, 18 August 2003, http://media.nara.gov/9-11/MFR/t-0148-911MFR-00269.pdf This memorandum refers to the traders involved in the Stratesec purchase. From the references in the document, we can make out that the two people had the same last name and were related. This fits the description of Wirt and Sally Walker, who are known to be stock holders in Stratesec. Additionally, one (Wirt) was a director at the company, a director at a publicly traded company in Oklahoma (Aviation General), and chairman of an investment firm in Washington, DC (KuwAm Corp).

- Ibid

- Sourcewatch.org, Profile for Mansoor Ijaz/Sudan

- Dan Briody, The Iron Triangle: Inside the Secret World of The Carlyle Group, Wiley publishers, 2003

- The Washington Post, obituary for WIRT D. WALKER – Intelligence Analyst, June 15, 1997

- Kevin R. Ryan, The History of Wirt Dexter Walker: Russell & Co, the CIA and 9/11, 911blogger.com, 3 September 2010

- Wikipedia page for Emery Roth

- The Washington Post, Times Herald, Dr. C.S. White Jr., 48, Surgeon, Chief of Staff, April 13, 1964

- The Washington Post, Times Herald, White-Walker wedding announcement, April 29, 1971

- Richard Harris Smith, OSS: The Secret History Of America’s First Central Intelligence Agency, Globe Pequot, 2005

- Alec Benn, The Unseen Wall Street, of 1969 to 1975: And Its Significance for Today, Quorum Books, 2000

- Donald Morrison, Ambush on Wall Street, Texas Monthly, April 1974

- Standard & Poor’s Security Dealers of North America, Volumes 109-120

- SEC News Digest, Issue 93-47, March 12, 1993

- Bloomberg Businessweek, Stifel Nicolaus & Company, Incorporated Hanifen Imhoff Division

- Bertie Charles Forbes, Forbes, Volume 153, Issues 8-13, 1994

- Ibid

- Although there is considerable variation in the English spellings of Kuwaiti names, Mish’al Yusuf Saud Al Sabah and Saud Nasir Saud Al Sabah (along with Saud Nasir’s daughter, Neira) are listed in Al-Sabah: history & genealogy of Kuwait’s ruling family, 1752-1987, by Alan Rush. See pp 132 and 133

- Mitchel Cohen, How the War Party Sold the 1991 Bombing of Iraq to US, AntiWar.com, December 30, 2002

- Susan Trento, The Power House: Robert Keith Gray and the Selling of Access and Influence in Washington, St. Martin’s Press, 1992 pp 93-96, 258, and 379-383

- New York County Supreme Court, Matter of World Trade Ctr. Bombing Litig, 2004 NY Slip Op 24030 [3 Misc 3d 440], January 20, 2004

- Securacomm Consulting Inc. v. Securacom Incorporated, United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, January 20, 1999, 49 U.S.P.Q.2d 1444; 166 F.3d 182

- Kevin Phillips, American Dynasty, Viking Penguin,2004, p 279

- Joseph Trento, Prelude to terror: the rogue CIA and the legacy of America’s private intelligence network, Carroll & Graf, 2005

- Report from the Joint Congressional Inquiry into 9/11

- Margie Burns, The Best Unregulated Families, The Progressive Populist, 2003

- The Washington Post, Four Planes, Four Coordinated Teams, 2001, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/nation/graphics/attack/hijackers.html

- Embry-Riddle University media, Embry-Riddle Alumnus Cleared of Reported Hijacker Link, September 21, 2001

- In the weeks after 9/11, many mainstream news sources reported that the accused hijackers were still alive. These claims were reported by major media sources like The Independent, the London Telegraph and the British Broadcasting Corporation. Although BBC attempted to retract the claims later, the Telegraph reported that it had interviewed some of these men, who the newspaper said had the same names, same dates of birth, same places of birth, and same occupations as the accused. See David Harrison, Revealed: the men with stolen identities, The Telegraph, 23 Sep 2001

- Securities and Exchange Commission, Form 8-K for Aviation General, Incorporated, March 26, 2004

- Alex Beam, He’s Back, The Boston Globe, November 19, 1990

- Catherine Hinman, A Joint Venture Of Business, Philosophy Secor Group Partner Has Will To ‘Win Or Lose It All’, The Orlando Sentinel, February 01, 1988

- Margie Burns, Trimming the Bushes: Family Business at the Watergate, Washington Spectator, February 15, 2005

- Spartacus Educational, Profile for Theodore (Ted) Shackley, http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/JFKshackley.htm

- Spartacus Educational, webpage for Theodore (Ted) Shackley

- Joseph Trent, Prelude to Terror

- David Corn, Blond Ghost: Ted Shackley and the CIA’s Crusades, Simon & Schuster, 1994

- David Corn, Blond Ghost

- U.S. Senate Report, Deposition of Ted Shackley in the Iran-Contra Investigation, United States Congressional Serial Set Serial Number 13766, United States Government Printing Office Washington: 1989. See Joseph Trento, Prelude to Terror, for reference to Razmara as a SAVAK agent.

- Spectrezine, Bush-Law in the Land of Mannon, http://www.spectrezine.org/resist/bush.htm

- U.S. Senate Report, Deposition of Ted Shackley in the Iran-Contra Investigation

- Suzan Mazur: John Deuss – The Manhattan projects, Scoop News, September 22, 2004

- Nancy Lewis, Defendant Backed in Kuwaiti Case; Royalty Allegedly Allowed Use of Fund, The Washington Post, May 31, 1988

- Larry J. Kolb, America at Night: The True Story of Two Rogue CIA Operatives, Penguin, 2008

- Larry J. Kolb, America at Night

- Nancy Lewis, Ex-Kuwait Airways Official Testifies of CIA Ties, The Washington Post, October 21, 1987

- Peter Truell and Larry Gurwin, False Profits: The Inside Story of BCCI, The World’s Most Corrupt Financial Empire, Houghton Mifflin, 1992

- Traute Wohlers-Scharf, Arab and Islamic banks: new business partners for developing countries, OCDE Paris, 1983

- Peter Truell and Larry Gurwin, False Profits, p 297

- Wikileaks document 05KUWAIT4792, Public Prosecution Questions Ruling Family Member About His Public Criticism Of GOK, dated November 16, 2005, http://www.cablegatesearch.net/cable.php?id=05KUWAIT4792

- Larry J. Kolb, America at Night, Riverhead Books, 2007

- Jim Crogan, The Terrorist Motel: The I-40 connection between Zacarias Moussaoui and Mohamed Atta, LA Weekly, July 24, 2002

- See FBI summary document for Marwan Al-Shehhi, accessed at Sribd, 911DocumentArchive, http://tinyurl.com/bnp7vrr

- See FBI summary documents for Saeed Al-Ghamdi and Hani Hanjour found in 911 archives at Scribd.com: http://www.scribd.com/911DocumentArchive

- Wiley Post Airport website, Airport Guide

- NewsOK, Dean N. Thomas obituary, December 7, 2000

- Rick Robinson, Aircraft Manufacturer to Keep Lease at Oklahoma City-Area Airport, Daily Oklahoman, December 29, 2001

- Aviation General Inc, Form 8-K, March 26, 2004

- UK Mail Online, Plane crashes into Milan tower, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-110475/Plane-crashes-Milan-tower.html

- Margie Burns, Bush-Linked Company Handled Security for the WTC, Dulles and United, Prince George’s Journal, February 4, 2003

- Legal Metric, WALKER, et al v. MONES, et al, District of Columbia District Court,

- Washington Business Journal, Chantilly Firm Folds Under Factoring, September 29, 2003

- SEC filing for Bankest Capital, SC 13D, March 13, 2003

- Ibid

- Reuters, Former exec to pay $165 million in fraud case, Aug 28, 2007

- Peter Zalewski, The Accounting: Indictments, receiver’s report on Bankest Capital present picture of a $170 million mystery, Daily Business Review, November 22, 2004

Photo courtesy of Raphael Concorde.