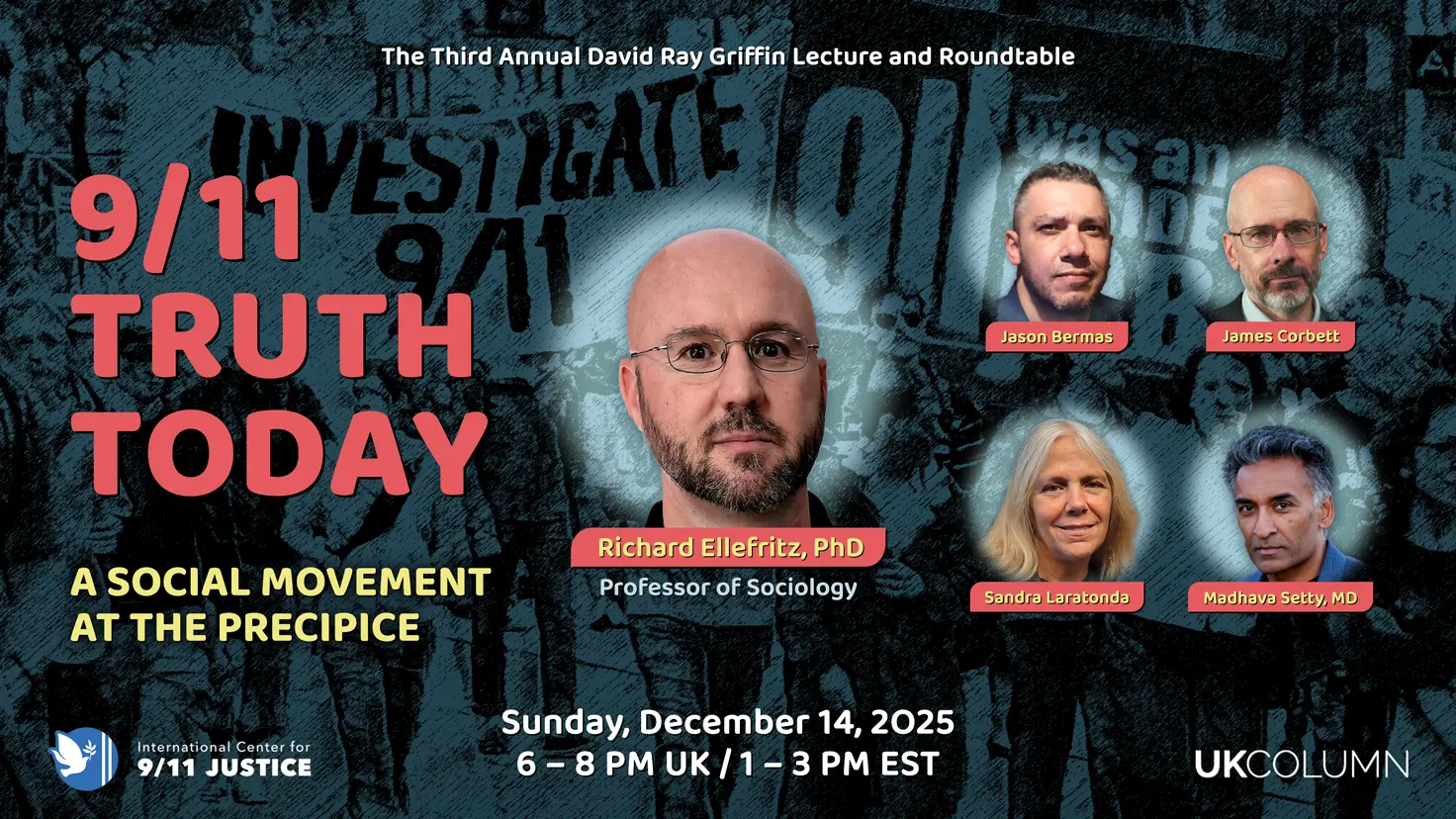

On December 14, 2025, Professor Richard G. Ellefritz delivered the Third Annual David Ray Griffin Lecture, an end-of-year symposium hosted by the International Center for 9/11 Justice and UK Column in honor of the late Dr. David Ray Griffin.

Before the lecture, 9/11 family member Matt Campbell joined Ted Walter to discuss the latest breakthrough in his family’s effort to secure a new inquest into the death of his brother Geoff, and Dr. Madhava Setty gave introductory remarks.

Following the lecture, Dr. Setty facilitated an insightful roundtable discussion with Ellefritz and some of the most powerful voices in the 9/11 Truth movement today: Jason Bermas, James Corbett, and Sandra Laratonda.

Below is a video of the event divided into sections. Under the lecture and roundtable sections, we have provided detailed synopses to help viewers navigate and absorb the complex material and discussion topics. There are also links to various supporting materials related to Ellefritz’s lecture.

Opening Remarks

Ted Walter | 16 minutes

A 9/11 Family Goes to the UK Supreme Court

Ted Walter and Matt Campbell | 14 minutes

David Ray Griffin and 9/11 Truth Today

Madhava Setty, MD | 15 minutes

9/11 Truth Today: A Social Movement at the Precipice

Professor Richard G. Ellefritz | 1 hour 8 minutes

Speaker Bio

Richard G. Ellefritz is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of The Bahamas. He earned his Ph.D. in sociology at Oklahoma State University after successfully defending his dissertation on how the conspiracy label is used to avoid offering direct and rigorous rebuttals to empirical claims made by so-called conspiracy theorists. His research interests range from conspiracy discourse to pedagogical techniques, and his main occupational focus is on teaching a variety of courses in the social and behavioral sciences.

Resources

Abstract

Professor Richard G. Ellefritz’s lecture advances an epistemological critique of how challenges to official accounts of September 11, 2001, are delegitimized within contemporary public and academic discourse. Drawing on conflict sociology, stigma theory, and social-movement analysis, Ellefritz argues that the label “conspiracy theory” functions less as an evaluative category than as a boundary-maintenance mechanism that preempts empirical engagement. He contends that the 9/11 Truth Movement has been systematically mischaracterized as epistemically deficient, despite its ongoing empirical research, methodological pluralism, and engagement with institutional actors. By contrast, Ellefritz suggests that many anti-conspiricist frameworks rely on psychological pathologization and rhetorical dismissal rather than sustained evidentiary analysis. The lecture reframes 9/11 Truth as a legitimate, empirically grounded social movement and contributes to a growing body of scholarship that challenges prevailing assumptions about rationality, dissent, and knowledge production in politically sensitive contexts.

Section-by-Section Synopsis

1. Conflict Sociology and the Question of Power

Ellefritz opens by situating his analysis within conflict sociology, drawing on the early-twentieth-century work of Georg Simmel and Max Weber. From Simmel he takes the central analytical question “cui bono”—Latin for “who benefits”—and applies it to conflict, secrecy, and elite interaction. From Weber he draws a theory of social stratification, in which status groups maintain privilege through authority, honor, and institutional position.

A key concept here is social closure: elites create boundaries that separate insiders from outsiders, with outsiders typically serving or working for those in power. This framework establishes how authority and legitimacy are preserved and why challenges to dominant narratives are often treated as threats rather than contributions to knowledge.

2. The State, Crisis, and the Utility of Problems

Ellefritz then turns to the sociological definition of the state as the entity that monopolizes the legitimate use of force. He argues that crises are not merely endured by such institutions but are often organizationally useful, because problems justify solutions—and institutions that control solutions benefit from the persistence of problems.

Within this framework, the wars of aggression launched after 9/11 become a central concern of the 9/11 Truth Movement, whose call for investigation is framed not as abstract skepticism but as an effort to address questions of war, peace, justice, and truth that remain unresolved decades later.

3. Ideological Power and Structural Power

Ellefritz distinguishes between two broad sociological approaches to power. One focuses on ideology, drawing on Steven Lukes’s argument that the most effective form of power is preventing certain issues from arising at all by shaping discourse and perception. Media, education, and other ideological institutions play a central role here.

The second approach focuses on power structures, drawing on the work of C. Wright Mills, G. William Domhoff, and Peter Phillips, and includes analysis of elite networks and institutional interlocks. Ellefritz notes that concepts such as the “deep state,” often dismissed today as right-wing rhetoric, actually originated in left-wing critical scholarship (notably Peter Dale Scott), illustrating how ideological framing itself serves elite interests.

4. Framing, Recruitment, and Political Insiders

At a more micro-sociological level, Ellefritz examines framing processes and the importance of recruiting institutional insiders. He highlights figures such as Senator Ron Johnson, whose call for new Senate hearings on 9/11 represents a potential institutional mechanism for reopening investigation, and former Congressman Dennis Kucinich, whose engagement with 9/11 Truth goes beyond symbolic endorsement.

Media framing, however, often neutralizes these developments through selective representation and stigmatizing labels, reinforcing boundaries between legitimate and illegitimate discourse rather than engaging the substance of the claims.

5. Stigma, Labeling, and Moral Panic

Drawing on Erving Goffman’s work on stigma and Howard Becker’s labeling theory, Ellefritz explains how the label “conspiracy theorist” functions to spoil identity and disqualify individuals as reasonable interlocutors. This process creates insiders and outsiders of permissible discourse and parallels earlier sociological analyses of moral panics and symbolic crusades.

Rather than addressing evidence, the label “conspiracy theorist” itself performs the work of exclusion. Ellefritz emphasizes that this stigmatization is not accidental but a routine feature of how controversial claims are managed in modern societies.

6. Media, Propaganda, and Cascading Narratives

Ellefritz situates 9/11 within established media-studies frameworks, including Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model and Robert Entman’s cascading activation model. Official narratives originate with state actors, cascade through mainstream media, and become normalized in public consciousness.

Fear-based messaging—such as color-coded terror alerts—played a key role in reinforcing these official narratives. Within this context, Ellefritz characterizes the 9/11 Commission Report as a text that can be analyzed sociologically as a propaganda artifact rather than a neutral investigation.

7. Authority, Debunking, and Popular Mechanics

Using media examples such as Popular Mechanics and televised appeals to institutional authority, Ellefritz examines how debunking often substitutes credentials and tone for substantive engagement. He notes that successive editions of Debunking 9/11 Myths failed to address direct rebuttals, including David Ray Griffin’s later responses, while continuing to recycle earlier claims.

Here, Ellefritz implicitly advances an important analytical point: although the 9/11 Truth Movement is often accused of operating outside empirical standards, it is anti-conspiricist efforts such as Popular Mechanics that more closely resemble a degenerating research program—avoiding anomalies, declining to engage counter-evidence, and relying increasingly on rhetorical dismissal rather than explanatory development.

8. Network Power and Interlocking Directorates

Ellefritz introduces network analysis to show how media institutions are embedded within broader corporate and defense-industry structures through interlocking directorates. He stresses that this form of analysis is standard sociological practice yet is frequently dismissed as conspiratorial when applied to sensitive political topics, reinforcing the very stigmatization he has been describing.

9. Pathologization, Anti-Conspiricism, and Epistemology

A major portion of the lecture critiques psychological and social-scientific approaches that pathologize belief in conspiracy theories. Ellefritz explicitly aligns his analysis with Lee Basham and Matthew R. X. Dentith, referencing Basham and Dentith’s co-authored article “Social Science’s Conspiracy Theory Panic” and Dentith’s book Taking Conspiracy Theories Seriously.

These works challenge the tendency to presume irrationality in advance of investigation and to rely on survey correlations, belief clustering, and stigmatizing concepts such as dysrationalia, crippled epistemologies, or degenerating research paradigms without engaging primary evidence.

Ellefritz makes clear—sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly—that the charge of being “not empirically grounded,” so often leveled against the 9/11 Truth Movement, more accurately describes anti-conspiricist scholarship itself, which frequently avoids empirical engagement in favor of psychological dismissal.

10. State Crime, Delegitimation, and deHaven-Smith

Ellefritz’s analysis converges with Lance deHaven-Smith’s concept of State Crimes Against Democracy, which emphasizes how large-scale abuses of power are obscured through institutional denial and delegitimation rather than lack of evidence. Within this framework, stigma and ridicule function as tools that protect official narratives from scrutiny.

Together, Basham, Dentith, deHaven-Smith, and Ellefritz articulate a shared epistemological position: The conspiracy label operates as a mechanism for avoiding empirical confrontation, not resolving it.

11. The 9/11 Truth Movement as Ongoing Research and Activism

Ellefritz characterizes the 9/11 Truth Movement as empirically engaged and methodologically diverse, citing ongoing work on seismology, structural analysis, and the free-fall collapse of World Trade Center 7. Drawing on Laura Jones, he situates the movement within the sociology of social movements and emphasizes its redefinition of patriotism as a constitutional obligation to question power.

Concepts such as “conspiratorial imaginaries” are clarified as cultural frameworks that sustain collective action, not indicators of irrationality.

12. Conclusion

Ellefritz concludes that the 9/11 Truth Movement remains a multifaceted, evolving effort to challenge dominant definitions of reality. Far from being empirically vacuous or socially deviant, it exhibits the features of a progressive research program, continually engaging new evidence and recruiting institutional allies despite persistent stigma.

The lecture ultimately reframes the debate: the central issue is not whether conspiracy theories are dangerous, but whether power can be questioned without dissent being pathologized.

Roundtable Discussion

Professor Richard G. Ellefritz, Jason Bermas, James Corbett, Sandra Laratonda, and Madhava Setty, MD | 1 hour 11 minutes

Discussion Topics

1. Teaching Critical Thinking Rather Than Prescribing Conclusions

Richard G. Ellefritz explains that his pedagogical focus is on teaching students how to think critically about power and authority rather than teaching specific conclusions about 9/11. Madhava Setty reinforces this framing by stressing the broader educational importance of cultivating discernment rather than indoctrination.

2. Straw-Man Debunking and Guilt by Association

Jason Bermas describes how 9/11 Truth is routinely discredited by being associated with fringe beliefs such as Flat Earth or QAnon, allowing critics to dismiss serious evidence without engaging it.

3. Hijacker Anomalies and Ignored Early Reporting

Jason Bermas outlines early mainstream reports indicating alleged hijackers’ ties to U.S. military bases, intelligence-linked individuals, and FBI informants that later vanished from public discussion.

4. The Mechanics of Straw-Man ‘Debunks’

Jason Bermas explains how debunking outlets rely on claims of “retractions” without demonstrating how the original reporting was disproven, thereby avoiding engagement with the broader evidentiary record.

5. Public Awareness as a Precondition for Institutional Action

Jason Bermas recounts Senator Ron Johnson’s view that evidence must gain public traction before official investigations or hearings become politically viable.

6. The Long Absence of Executive Accountability

Jason Bermas situates 9/11 within a broader historical pattern of impunity, noting the lack of meaningful accountability since Iran-Contra.

7. Internal Skepticism and Self-Correction Within the Movement

James Corbett challenges the stereotype that the 9/11 Truth Movement lacks internal critique, explaining that serious researchers regularly revise or abandon claims when confronted with better evidence.

8. Cognitive Dissonance and Psychological Resistance

James Corbett discusses the emotional difficulty many people experience when confronting evidence that threatens their worldview. Madhava Setty adds that such resistance is a common human response to existential threat, not a sign of intellectual deficiency.

9. Sociological Perspectives on Resistance to Evidence

Richard G. Ellefritz supplements the psychological discussion by describing interviews with activists who initially rejected 9/11 Truth but found certain evidence—especially regarding World Trade Center 7—impossible to dismiss.

10. Algorithmic Suppression and Platform Gatekeeping

Jason Bermas provides firsthand examples of age restrictions, warning labels, and algorithmic suppression applied to 9/11-related content on platforms such as YouTube.

11. Partial Openings and Persistent Failures in Alternative Media

Jason Bermas critiques alternative-media figures who reopen discussion of 9/11 while repeating serious errors or omitting crucial context.

12. Unexamined Documentary and Legal Evidence

Jason Bermas highlights extensive court records, intelligence documents, and civil-litigation material that remain largely unexamined by both mainstream media and academia.

13. The 1993 World Trade Center Bombing as Precedent

Jason Bermas draws parallels between the 1993 bombing and 9/11, particularly regarding FBI informant involvement and institutional misconduct.

14. Prospects and Limits of New Senate Hearings

Richard G. Ellefritz questions whether any credible experts could publicly defend NIST’s explanation of WTC 7, while Jason Bermas emphasizes that hearings would primarily establish a public record rather than deliver immediate prosecutions.

15. Is the Movement at an Inflection Point?

James Corbett argues that structural resistance has remained largely constant, with recent changes driven more by shifts in the media environment than by institutional reform.

16. Evolution of the 9/11 Truth Movement Over Time

Sandra Laratonda traces the movement’s progression from early street activism to credentialed organizations such as Architects & Engineers for 9/11 Truth, followed by fragmentation and maturation.

17. Grassroots Organizing Versus Information Saturation

Sandra Laratonda emphasizes that while information is widely available, motivating people to take sustained action remains a central challenge.

18. Internal Dynamics, Gatekeeping, and Fragmentation

Sandra Laratonda and James Corbett discuss factionalism, accusations of gatekeeping, and the difficulty newcomers face navigating competing theories and organizational divisions.

19. Evidence-First Engagement Versus Broader Worldview Framing

Richard G. Ellefritz argues for prioritizing concrete physical evidence—particularly WTC 7—when engaging newcomers, warning that broader geopolitical implications can overwhelm audiences if introduced too early.

20. Fragmentation and Public Confusion

Sandra Laratonda explains how the proliferation of theories and organizations can make it harder for newcomers to distinguish strong evidence from speculation.

21. Distribution as the Central Bottleneck

Jason Bermas maintains that distribution, not discovery, has long been the primary obstacle to wider public understanding.

22. Post-COVID Shifts in Public Skepticism

Jason Bermas notes that COVID-era government and media behavior has increased public openness to questioning official narratives.

23. Defining “Victory” for 9/11 Truth

James Corbett frames success in terms of historical recognition and preventing future wars, while Sandra Laratonda emphasizes cultural and educational impact.

24. Internal Discord as the Greatest Obstacle

James Corbett warns that internal conflict could undermine genuine breakthroughs, including hearings or high-profile films.

25. Objective Evidence Versus Relativism

Jason Bermas forcefully distinguishes physical evidence—such as free-fall collapse and molten metal—from subjective interpretation, rejecting relativism in matters of science.

26. Psychological Courage and Democratic Responsibility

Richard G. Ellefritz closes by emphasizing the courage required to confront institutional deception and frames this as a civic responsibility necessary to prevent future harm.